How VFX Icon Douglas Trumbull Saved Star Trek: The Motion Picture From VFX Embarrassment

The story is familiar to Trekkies. When "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" was in production in the late 1970s, SFX guru Douglas Trumbull was busy completing work on Steven Spielberg's "Close Encounters of the Third Kind." Paramount asked Trumbull to work on their movie, but he turned them down. Not only was not quite done with "Close Encounters," but he was eager to return to a personal project of his, the development of Showscan. Showscan was a new filming process that ran high-fidelity 70mm film through a camera at 60 frames per second, allowing for crystal clear images and more natural movement. Although such a process had the potential to revolutionize the film industry, Paramount didn't care. There was a rumor that Paramount managed to get Trumbull's Scowscan funding cut as revenge for not working on "Star Trek."

Instead, Paramount hired Robert Abel and Associates to develop then-novel CGI for "Star Trek." Abel was from the world of TV commercials and had already done a lot of work with advanced CGI, some of which can be seen in old demo reels. Abel constructed a physical model of the U.S.S. Enterprise and intended to put it into CGI space environments.

After a year of work and spending about $5 million, however, Abel's studio was unable to produce a single useable VFX shot for "Motion Picture." CGI was a good idea, but it seems the tech wasn't quite ready yet. Abel was fired. With only seven months until the film's set release date, Paramount hired Trumbull out of sheer desperation. What followed was the most stressful seven months of Trumbull's life as he rushed to make something that looked halfway decent.

Trumbull talked about those miserable months in a 2019 with TrekMovie. He more or less saved the movie from disaster.

Here's to seven miserable months

Trumbull recalls the time clearly, saying:

"[W]e had 7 months. It was a real crash program. We had to do all the visual effects work. There were as many shots in 'Star Trek: The Motion Picture' as 'Star Wars' and 'Close Encounters' combined, and it was a big problem. It took a massive effort to try to pull it off. We had visual effects crews working 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, for the entire period."

Trumbull famously worked himself into the hospital, having given himself ulcers from the stress. He also required a lot of help and had to call in another one of Hollywood's better-known VFX guys, John Dykstra, to collaborate. The two had known each other through a familial connection, and some mutual work that Trumbull's father had been doing. This, however, required a weird meshing of film formats, as Trumbull liked 70mm and Dykstra worked in 35. Trumbull said:

"After [the Southern California branch of Industrial Light & Magic] was closed by George Lucas, John and his pals, including my father, Don Trumbull, formed a new company called Apogee, to do visual effects for films. And they had a really good track record and were doing really great work. So we collaborated with them, and we had to figure out how to do part of the visual effects in 65-millimeter negative, and part of the visual effects in 35-millimeter VistaVision, because we were both using different techniques."

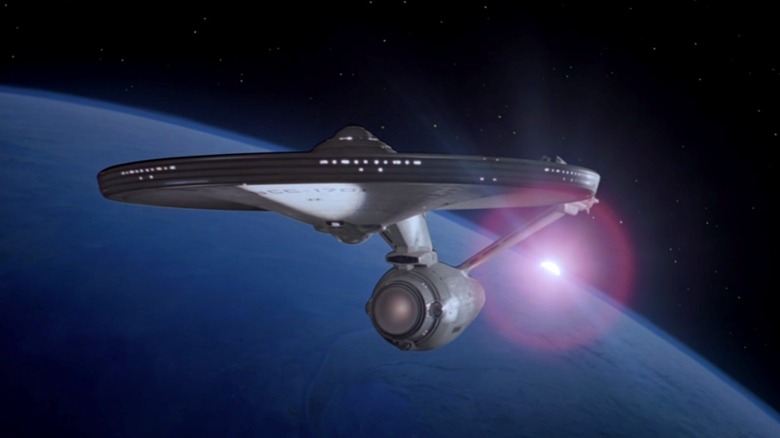

Trumbull also revealed that he had to build a new model of the U.S.S. Enterprise with its own light-up windows. Evidently, Robert Abel's model had little detail and no lights, and Trumbull felt he couldn't point a camera at such a dull-looking model.

The Enterprise model

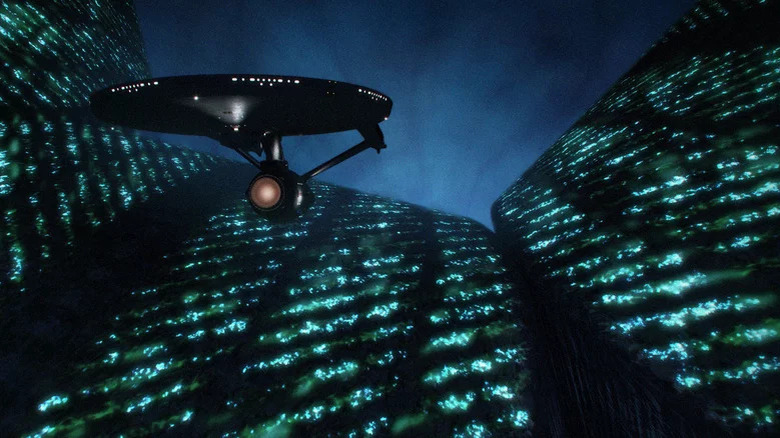

Trumbull knew that the Enterprise had to be impressive. The goal of "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" was to translate the low-fi adventures from the 1966 TV series into something outsize and cinematic. A lot of energy was spent making the U.S.S. Enterprise look enormous and real. Trumbull saw what Abel had been working on and was baffled. He quickly swept in, built a new model, and rearranged the entire filming process. Trumbull said:

"The first task we took on was to basically redesign the ship, and make it so that it could light up itself, with light sources on the body. So it looked really great even with no key light, and there was a tremendous amount of detail painted on the surface. And then part of that was the dry dock sequence, which was also misconstrued. They had really crazy ideas at this previous company, to shoot in separate passes, and then composite them optically, which in my opinion was just never going to work, and it was not necessary."

A key light is a light source that shines directly on the subject. "Multi-pass" effects involved shooting the ship in one pass, the warp engines in a second, the windows in a third, etc., and then compressing them all down into a single shot. Trumbull said there was no point in doing it that way. He continued:

"We had to redesign the lighting and everything in the dry dock to make it work with the craft. So that was the first thing. And then there were other miniatures that had been built for the orbiting space station and stuff like that, that had to be done better and illuminated better and rigged up for motion control photography."

He did it better. And thank goodness.