The Late Film Editor Who Was Quentin Tarantino's Secret Weapon

In 2009, Sally Menke, the splicer extraordinaire who cut her way to film industry prominence as Quentin Tarantino's most trusted collaborator, wrote, "Editors are the quiet heroes of movies and I like it that way." I emphatically agree and disagree with this observation. On one hand, the best film editing is seamless; watching a movie should be an entrancing experience, and it's the editor's job to not break the spell. Yes, there are singular, medium-altering cuts (the entire Odessa Steps sequence in Sergei Eisenstein's silent classic "Potemkin;" the blowing out of a match whisking us off to the desert in David Lean's "Lawrence of Arabia;" the bone-to-spaceship transition in Stanley Kubrick's "2001: A Space Opera"), but they're grand gestures deftly woven into the fabric of the movie. They pull you deeper into their worlds, not take you out of them.

Watch enough movies, however, and you become attuned to certain editorial rhythms. After a while, you can sense early on when a great director has been knocked off his A-game. For example, Lean's "Doctor Zhivago," his epic follow-up to "Lawrence of Arabia," might look and sound the part of a masterpiece on occasion (thanks to the contributions of screenwriter Robert Bolt, cinematographer Freddie Young, and composer Maurice Jarre), but it's glacially paced from the start and never finds its gait. How did a god-level director coming off his finest work miss the mark so badly?

Anne V. Coates, the quiet hero of Lean's 1963 triumph, was loudly absent from the editing room.

Most filmmaker-editor relationships are not monogamous (Lean only worked with Coates once), but I do think it's telling that two of the best to step behind a camera, Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino, are/were fiercely committed to, respectively, Thelma Schoonmaker and Sally Menke. While I think both men were destined to be major artists regardless of whom they collaborated with, they were remarkably fortunate to grow as directors alongside such incredibly talented women.

And though Tarantino's made several great movies over the last 14 years, I miss that singular cinematic voice he shared with Menke.

A long walk interrupted

Sally Menke died at the age of 56 on September 27, 2010. I remember the day well. The asphalt-melting heat wave that had gripped Los Angeles for most of the month peaked with a 113-degree banger. I tried to walk five blocks that afternoon, and, while laboring back uphill to my Tamarind Avenue apartment, I called my friend Damon so I'd have someone on the line if I fell out.

A couple of miles northeast, Menke, an avid hiker, was out on a Griffith Park trail with her dog. Coincidentally, Menke had been hoofing it in Banff, Alberta almost 20 years prior when she hopped in a phone booth and learned she'd been hired to edit "Reservoir Dogs." Tragically, the extreme heat of that wretched day proved too much for Menke. Her body was discovered at the bottom of a ravine in Griffith Park.

For anyone who cared about movies, this was not a quiet death. And it tore Tarantino's heart out.

It's Travolta - dancing in front of me

Menke was as much of a living legend as Tarantino. Film critic Elvis Mitchell, who knew her personally, called Menke a "sensualist." I can only judge the films from the heat emanating off the screen, but once Tarantino got past the macho posturing of "Reservoir Dogs," his films acquired a carnal charge. John Travolta and Uma Thurman's dinner flirtation at Jack Rabbit Slim's is, for all the adorkable banter, hot stuff; Thurman's accidental heroin overdose keeps the pair from taking it to the bedroom, but they scratch that itch in an unforgettably goofball manner via their prize-winning dance to Chuck Berry's "You Never Can Tell."

This was only Menke's second feature with Tarantino, but, while cutting the unconventionally shot Jack Rabbit Slim's dance (Tarantino had his stars get down to playback on the set), she knew she'd found a kindred creative spirit. As she wrote in her 2009 The Guardian essay:

"[O]h my God, it was glorious. We chatted about using the long shot, the medium close-ups, and when to focus on the hands. Most editing is painstaking but this was an exciting scene to edit because it had momentum of its own and an obvious magic – it's Travolta, dancing in front of me."

When it comes to the editing, I write with Sally

With its non-chronological narrative and myriad verbal digressions, "Pulp Fiction" is one great big two-and-a-half-hour magic act. Had Tarantino made the film at a major Hollywood studio, he likely would've been encouraged to vacuum out the space and vanish moments like Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson hanging back to debate whether a foot massage can be construed as a subtle form of seduction — which means we would've been deprived of Menke getting around what could've been an awkward edit by inserting Travolta's next line of dialogue a half-beat before cutting to the rear shot of the duo in front of the door. This may sound kind of in-the-weeds, but watch the sequence and observe how one invisible editorial flourish can make a massive difference. Now that's some quiet heroism.

Menke had a musical ear when it came to editing long dialogue scenes, but, oddly, given her collaborator's love for layering these moments with needle-drop cues, she preferred to make her first pass sans music. "I just make the scene work emotionally and dramatically," she said, "And then Quentin will come in and lay the track over it and we'll tweak it to the beats." For Tarantino, the entire editorial process is something of a rewrite. "I write by myself," he said. "But when it comes to the editing I write with Sally. It's the true epitome, I guess, of collaboration because I don't remember what her idea was, what was my idea."

How Menke helped Tarantino capture the ache of middle age

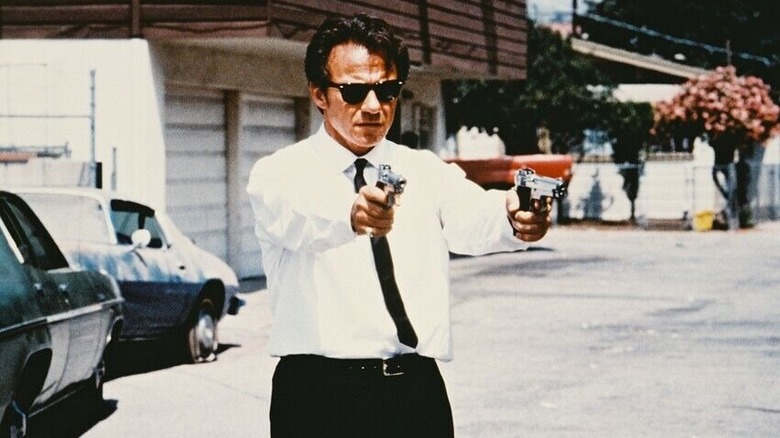

Their editing suite pas de deux went full Astaire-Rogers with 1997's "Jackie Brown" — though not everyone was initially pleased. After the dazzling movie-movie shenanigans of "Pulp Fiction," the director's fanboys were amped for a wild meta ride, while critics were hoping to see signs of maturity from the new enfant terrible of American cinema. I think "Jackie Brown" might've been too mature for the latter camp, but I know for a fact it was too sedate for his acolytes who adorned their dorm room walls with posters of Harvey Keitel two-fisting Smith & Wesson 639s in "Reservoir Dogs."

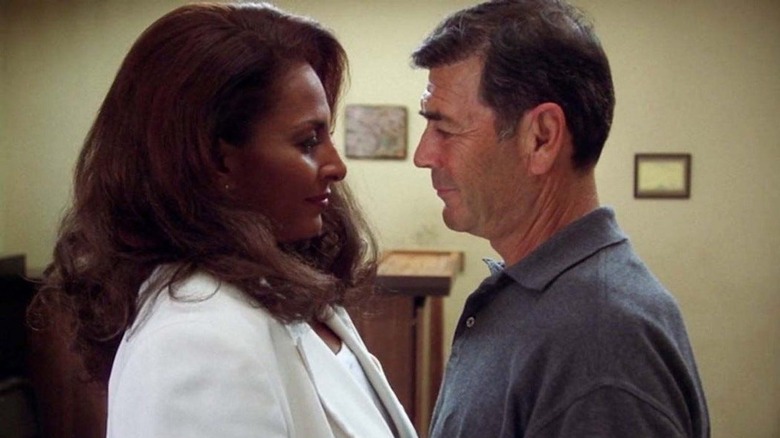

27 years later, both contingents have largely come around on "Jackie Brown," which luxuriates in Elmore Leonard's spiky repartee from "Rum Punch" while eschewing the barrage of pop culture references that turned his first two films into Gen X sensations. Surface-wise, it's an immensely satisfying crime yarn, but Tarantino and Menke dedicate a surprising amount of screen time to the middle-aged romance blossoming between Robert Forster's lonely bail bondsman and Pam Grier's over-it smuggler/flight attendant.

"Jackie Brown" is a wise movie about last-chance love, one I'm still surprised a 34-year-old Tarantino had kicking around in him. It's such a profoundly different experience from "Pulp Fiction" — relaxed, melancholy, human — that I've always felt this was the film where Menke's voice was most vital. She had 10 years on the brash thirtysomething (who spent a portion of 1997 bragging about backhanding contentious producer Don Murphy in a trendy West Hollywood restaurant), and, though happily married (to "Galaxy Quest" director Dean Parisot), could empathize with the movie's essential middle-aged ache. Tarantino wouldn't hit these heartbreaking notes again until 2019's "Once Upon a Time in Hollywood."

And he wouldn't have gotten the opportunity without "Kill Bill."

Our style is to mimic, not homage

I don't know that I've ever seen a director make a bolder aesthetic leap than Quentin Tarantino did between "Jackie Brown" and "Kill Bill," and I can't imagine an artist as particular as QT sticking the landing with such blow-the-roof-off bravado without an editor who, essentially, shared a brain with him.

"Kill Bill" is a meta-referential masterpiece that could only spring from the mind of a movie-mad 1980s video store snob (entire companion books full of annotations have been written about the film). It had to play and look a certain way, which could've been daunting for Tarantino because he'd never made a movie that played and looked anywhere close to this. He'd directed light bits of action here and there, but the House of Blue Leaves melee sequence required him to develop an entirely new skill set. And it presented Menke a whole new set of challenges in the editing room.

Working, as she typically did, from a rented house in Southern California (which allowed her to work through two pregnancies), Menke sorted through filmic influences ranging from Shaw Brothers martial arts flicks to Spaghetti Westerns. Complex fight choreography, wire work, dynamic cutting, extreme close-ups ... it's a smorgasbord of pulp cinema style, and it is nirvana.

"Kill Bill" might've been a giant leap in terms of scale, but Menke and Tarantino had the safety net of their conceptual ideology. Per Menke, "Our style is to mimic, not homage, but it's all about recontextualizing the film language to make it fresh within the new genre." They watched all kinds of movies in search of "the vibe," and they found something holy on the path to completing "Kill Bill." Could they top it? Did that matter? They'd hit the Scorsese-Schoonmaker sweet spot. They were a must-see combo. Tragically, we only got to see them work their magic two more times.

Hi, Sally!

A few days after Menke died, a reel of outtakes from "Death Proof," Tarantino's underrated slasher flick hybrid from the 2007 "Grindhouse" experiment, hit YouTube. Fans of the filmmaker knew that he loved peppering his dailies with glad tidings to his editor, who was holed up in a rented house far away from the shoot, but most people hadn't seen the actual footage.

Tarantino would have his time with Menke in post-production, but he loved her and wanted her to feel like a boots-on-the-ground part of principal photography. This is how he brought her onto the set. It's an endearingly affectionate act, one that likely never occurred to, say, Ridley Scott while he was dumping coverage on Pietro Scalia during the shoot of "Black Hawk Down."

A shared masterpiece

Menke considered the opening interrogation of "Inglourious Basterds," the last film she'd edit for Tarantino, the best thing they'd ever done. It's an excruciatingly tense scene intercut with perfectly timed shots of the Jewish family hiding beneath the floorboards of a French farmer's house. Tarantino and Menke lived for slow burns, and if she felt this was the apotheosis of their creative marriage — a legato passage of sinister sleuthing that crescendos to a staccato spasm of violence — I will not quarrel.

Menke isn't invisible here, nor is Tarantino. On the contrary, they're full of swagger. For my money, they hit their loping stride at the outset of the film's third act, when they execute a needle-drop coup de cinema by setting up Mélanie Laurent's fiery act of retribution via David Bowie's "Cat People (Putting Out Fire)" theme from Paul Schrader's 1982 remake of Jacques Tourneur's 1942 horror flick. The rhythmic cutting is expectedly spot-on, but the emotion of Laurent's Shoshanna — who, we realize through the war-paint application of her make-up, intends to die this evening — scorches our soul. She will perish, yes, but so will a theater full of Nazis, and they'll do so watching a propagandistic lie intended to bolster their genocidal spirits.

Porting Bowie's (initially unheralded) song from a tepidly received remake of a World War II-era movie into a modern film set in World War II is an epic feat of recontextualization. This is the ne plus ultra of the Tarantino-Menke anti-homage philosophy. This is their shared masterpiece. And it will never cease to suck that this is where their journey terminated.

So I implore you to never be quiet about Sally Menke. Shout her name. Spread her gospel. Live for the edit.