Suzume Director Makoto Shinkai Embraces The Idea Of Things Getting Lost In Translation [Exclusive Interview]

This post contains spoilers for "Suzume."

Makoto Shinkai is one of the most popular filmmakers that some Americans may not know about. Three of the director's films — the animated fantasy-dramas "Your Name," "Weathering With You," and his latest, "Suzume" — are among the ten highest-grossing Japanese films in history, and each tell stories of young people in intensely emotional, strange situations, like switching bodies, controlling the weather, and preventing natural disasters using magic.

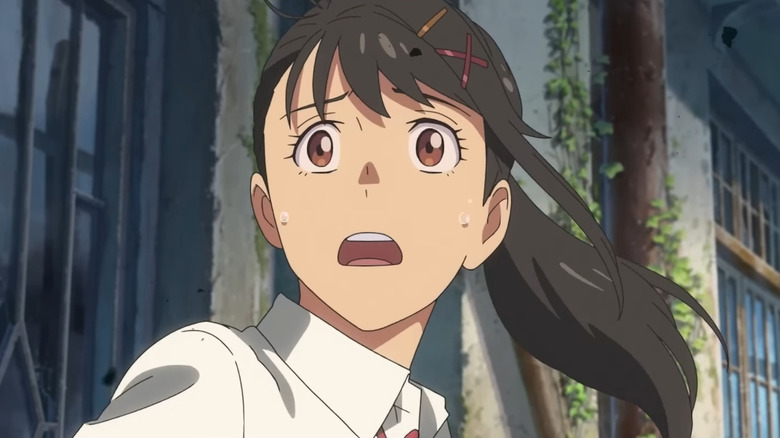

"Suzume," now on Crunchyroll, tells the story of a young girl who accidentally opens a door and unleashes a giant worm that only she and a college student, Souta, can see. If it escapes completely, the worm will cause a gigantic earthquake, so they have to close the door and seal it away as fast as they can. But when Daijin, the keystone that keeps the gate shut, leaves its post and takes the form of a cat, Souta and Suzume have to follow it across Japan before carnage can overwhelm the country. Making their job harder is the fact that Daijin has transformed Souta into a tiny three-legged chair, a gift that Suzume's late mother gave to her as a child.

We sat down with Makoto Shinkai (and an interpreter) to discuss the role that natural disasters play in so many of his films, the dangers of making certain characters too adorable, the film's amusing shout-out to Studio Ghibli, and how some elements of his movies don't come always across when they're localized for other countries ... and why he thinks those unlocalizable elements are actually a good thing.

Note: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

'The idea of this natural disaster has always been on my mind'

I want to start with the topic of natural disasters. A lot of your movies tend to involve natural disasters in their storyline. Is that something that just happens organically, or is that something that expressly, specifically interests you as a storyteller?

Initially as a filmmaker, I didn't really look at disaster as a core thematic element of my stories. It was more actually about this romance over a very long distance in time, or a story about adolescence and growth. A huge change happened to me in 2011, when the Great Eastern Japan earthquake struck. And of course there was a lot of death and a lot of damage that I think to this day, Japan is still trying to recover from. And as an animation director, I think it really affected me and had me seek the meaning behind what it is I'm creating. Over the next 10 years from the earthquake, I think the idea of this natural disaster has always been on my mind as a thematic element in developing my films, leading up to the most recent film, "Suzume."

"Suzume" is very much a film about mourning, or grief. It's a story about one character's mourning and a story about mourning on a larger scale. Do you feel as though the film is intended or effectually can help audiences deal with their own grief? Or, do you feel as though it was for you, perhaps, and your own emotional growth that the film is most powerful?

I think for me personally, I needed to make this film in some ways because after the disaster struck, there was a certain amount of kind of regret or lingering feelings that I had and that I don't consider myself a direct victim of it, but I was still affected. In doing so, the three films I made over the next 10 years, "Your Name," "Weathering With You" and "Suzume," was perhaps myself trying to understand what an animation director can do in a time when it didn't seem like a necessary good or service. So that resolution and understanding, I think, shaped in the form of these three films.

With "Suzume," I think how that affected both direct and indirect victims of the earthquake, depending on how close you were to the epicenter, through this film, I really can't speak to the effects and how it touched every person. Was it part of their own personal healing journeys? I don't know. Maybe, maybe not. I think a lot of that depends on when they've seen the film, how old they were, the environment, how the disaster affected them personally. But in spite of all of that, I never set out to make "Suzume," this film, of aiding people or telling people that, "Hey, this is how you come to terms with the disaster."

For me, first and foremost, making an engaged and very fun experience to the moviegoing audience was my first and primary priority. But of course, I as a filmmaker will try to offer something of value and some added value that I can provide. And as a result, if people are able to come to terms with and find meaning in that disaster, then that's great. But I wouldn't go so far as to say that, "Hey, this is what I was intending to do."

'I didn't want it to look and feel too much like a creature or monster like Godzilla'

Not all of my questions are this severe, but I have one more question on this topic. In the film, earthquakes are represented by a creature of sorts. It's called a worm in the translation. So many of your films are wonderful because they focus so much on character. Nobody does things just because the plot requires them to. They're very motivated. Is the worm or the earthquake a character? Does it have things that it wants? Is that something we can understand as an audience or even as a storyteller?

With regards to the worm and its expression and how it's shown on screen, I didn't want it to look and feel too much like a creature or monster like Godzilla, for example. Because once you visualize a creature that's very animal-like, then I think it will necessarily need to have some kind of motive or some kind of goal that we can understand and relate to, whether it's to destroy a city or defeat some kind of enemy, or fight something. Instead, the intention behind the worm is that it in and of itself is a force of nature. So I try to be very careful to not make it look too creature-like, and this disaster is also not driven by any one motive or anything. It just happens. So in a similar way, the worm, it wasn't intended to look too creature-like.

'The very nature of translating or interpreting something will come with its own set of loss'

I wonder if maybe that has something to do with the translation, that it was referred to as more of an animal. But it does raise a question about the way that your films translate to American audiences in a very literal way, and also in a broader context. And I want to talk about this in regards to just the film's title, which in America is "Suzume," the character's name. But in Japan, it is ["Suzume no Tojimari," translated: "Suzume's Locking Up"], the character doing something. It's an action. Do you believe that changes the context in which people will approach the film, or perhaps their takeaway from it, because it's suggesting what the emphasis is in the story?

Any time a film or work like this is localized — and this is not limited to just Japanese content or anime being localized for other regions, but even Hollywood films being localized for other regions around the world — there is some degree of almost cultural background that each country or culture will have that is more ingrained with the originating culture, as opposed to the ones it's being targeted or localized for. And I think the very nature of translating or interpreting something will come with its own set of loss. There's nothing you can do about that, just simply because of what words are available and what cultural backgrounds people have. And I think certain emotions, perhaps you can't even find the right words to use to express.

But I also find that process very interesting because of language and culture. You can't make something that's one-to-one. It's just a physical impossibility. But the fact that it doesn't exist, to me, is what makes multicultural projects or films quite interesting and engaging. Perhaps there might be some very subtle nuance or cultural background that Japanese people have that international audiences might not. But in spite of that, I think making a fun movie is at the core of what movie-making and filmmaking is all about. And if through some localization and some subtle nuance being lost through, whether it's a title or translation, if "Suzume" ceases to be a fun movie, then I think there's an issue with the movie itself and not necessarily the localization.

So in that sense, I think what I wanted to say in certain meanings in the core messages, the so-called spirit of the film itself is, at least I feel, is definitely conveyed, and it seems to me, just on audience reaction, that there is a fun movie there to be had.

'The chair is still able to stand on its own'

Well, it is a fun movie. I do want to clarify that. But a lot of it is the chair itself. It is such a distinct and, until we learn the deeper meaning of the chair, it seems like such a random thing to be transformed into. And I was wondering if you could talk about why a chair is meaningful as an entity, as itself, and also how you came to decide how this particular inanimate object would move, how that would be animated as its own unusual entity, and also why it only has three legs.

There are several reasons how I landed on the object of a chair, and I think it would be impossible to explain every single one of them. So I'll be selective and choose a few for the purpose of this conversation. The first one being, structurally in this film, it deals with the idea of disaster, but at the same time, it also deals with the idea of someone saving someone else. I had some imagery of the fairy tale of the prince turns to a frog, and through the princess's kiss, he's able to return back to his original form. It's very tried and true fairy tale that we all know, and it's got all the ... act one, two, three, it's all very simple. I wanted an element of that structure in my movie as well. But rather than the power of love somehow overcoming that challenge, but instead of it being any kind of animate object or animal like a frog or otherwise, I chose an inanimate chair.

When thinking about what inanimate object would be good, I landed on the idea of a chair as an object the parent would give to a child, because it actually happened in my own childhood when my father made a chair for me and gave it to me as a present. And it made me really, really happy, and I think that emotional connection is what Suzume shares with her mother as well. The reason it made me so happy was because, as a young kid, receiving your own piece of furniture, it almost feels like your own world, your own space, your own room, your house. It felt like my dad was giving that to me. So it really left a strong impression on me as a young kid. So perhaps young Suzume also had an equally strong connection with the chair when her mother gave it to her.

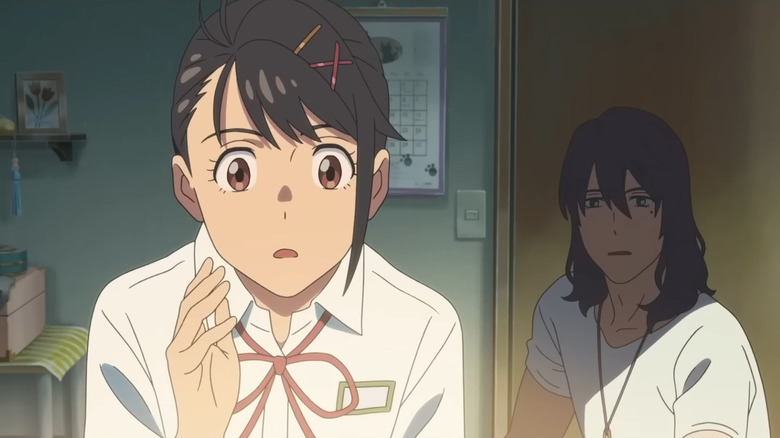

As for the reason behind it being a three-legged chair, there are also several reasons, but I'll focus on two. The first being, I wanted some comic relief in this film, because taken at face value, if you have a disaster film and take it too literally, then it's going to be a very dark and heavy film, I think, mood-wise. But in order to help balance and offset that and offer comic relief, a three-legged chair, just even walking on the screen, I think will have some effect of lightening up any scene that you're looking at.

And the other reason is Suzume, as a character, lost a resemblance of an ordinary life. She's been deprived and stripped of it, and she's lost her mother in this disaster that she experienced as such a young child. This idea of loss, I think in her heart and in her mind, there's a huge void. So the chair also metaphorically having lost one of its legs, I think represents that void in some ways. But in spite of that, the chair is still able to stand on its own. It's able to walk and it's able to run. So I think while carrying loss or these wounds, it's still possible to function and do everything that you need to.

'Perhaps we've illustrated and animated him too cutely'

In addition to the chair, we also have two cats, Daijin and Sadaijin. And at the end of the movie, I'm curious what you think this might say about me, is that as happy as I am for Suzume to have overcome what she has overcome and come to terms with her grief and have found love, I'm really sad that Daijin didn't get to be a cat. That has really stuck with me more than I perhaps expected it to. I'm curious what your thoughts are.

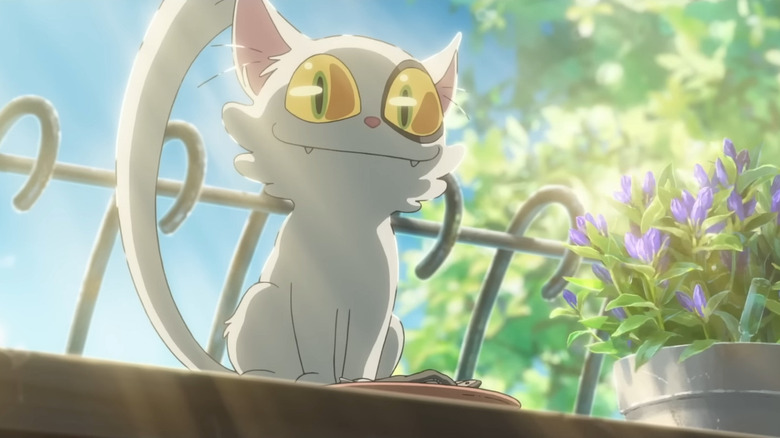

Actually, a similar sentiment is shared by audiences in Japan, certain audiences and demographics that they feel bad Daijin was stuck and he wasn't able to turn into a cat and resolve his own story. But in my mind, between the worm representing a grand force of nature in a similar way, Daijin as a cat is this massive god in some ways. It is divine by its nature, and that's how nature is being balanced, by these two gods, this force of nature and a god of sorts. So in that scene, what I was trying to depict is a god returning, or its divine being, returning to its normal occupation, so to speak, or restoring the balance. But perhaps because we've illustrated and animated him too cutely, people got attached to the catlike nature, and it returning to a god didn't land as I intended.

'That one scene has a little bit of an Easter egg [for] the die-hard Ghibli fans'

This might be me reading too much into it, but shortly before we meet Sadaijin, in the film there's a scene which Suzume and everyone are in a car and behind her we see a truck with a picture of a black cat. And I'm wondering if that's foreshadowing, if that is you being playful, or is that a detail I've read too much into?

I think it's very crazy of you to notice that because there are several things happening with that particular truck. If you're familiar with the movie "Kiki's Delivery Service" by Hayao Miyazaki, it's an homage, an Easter egg referencing that in some ways. So when they're in the car with Serizawa, he goes to the next track, which is in the Japanese title, "Rūju no Dengon" — "A Message Left in Rouge," or "Lipstick" in this case. And it's a song that almost the entire Japanese population has heard of, and it's a movie, "Kiki's Delivery Service," that almost the entire population has seen.

So to all the Ghibli fans, when he puts that track on, there's a character in "Kiki's Delivery Service," the black cat. There's the truck with that black cat and the music. And also the FedEx of Japan is called Kuroneko Yamato. The black cat is the logo of the FedEx of Japan. So there's a lot of things happening, and that company was a sponsor of the original "Kiki's Delivery Service" film. So that one scene has a little bit of an Easter egg [for] the die-hard Ghibli fans who know what's happening between that relationship.

'It's important to cherish what cannot be localized'

It's a really interesting time, I think, for animation as a medium. There are a lot of different filmmakers working in a lot of different styles. In America, we've seen a lot of different filmmakers trying to expand what animation is capable of as a storytelling medium after many years of it being very limited, and being considered very family-friendly. I'm curious, as a filmmaker who has made so many great films, what do you think the current state of animation is as an art form or as an industry, and what problems we may have currently today within that industry, that we — as animators, or even as audience members — have to be thinking about?

I think certainly animation has its own set of issues and problems as well as possibility, and to your point, a lot of people are trying to experiment with what can be done and push the boundaries and challenge the existing status quo of what animation has been limited and relegated to. I think there's a lot of different elements in your question and a lot of different nuance that I don't know if I can answer and cover everything. But I don't want to be seen as representing also the animation industry of Japan in its entirety. This is just a single creator's opinion. But I certainly want to expand our worldwide audience and footprint as well as expand my own fan base, because in Japan right now, I think there's more possibility for even older generations and people to experience what animation can deliver as a storytelling medium.

In terms of what animation can do and what we can do, I think to your point, it's important to know that ... you said perhaps there's some nuance that's lost, or some cultural background information that informs something that we might not necessarily understand that's based in certain detail. I think very much what I do is rooted in Japanese culture, and I think it's important to cherish what cannot be localized because it feels like there's something there. And yes, I know we're trying to expand to a more global audience and have more people engage and consume and understand and watch these films, and it might almost sound like reverse logic, but I think it's important to be very localized in what we take as a thematic element, and that's what's going to help animation expand to newer audiences, that factor that cannot be localized.

Because you look at companies like Disney or Pixar and they're already doing the super multicultural, something that it's for everyone, all audiences, all ages [type of filmmaking], and very intentionally done so. In order to almost differentiate or value add in a different way, I think it's important for us to bring in these subtle nuances that almost cannot be localized, but people still find engaging. So I think regardless of what I do in the future, I will continue to have that in my mind as I create new films.

"Suzume" is streaming now on Crunchyroll.