The Frustration That Drove Was Craven To Finally Make New Nightmare

The 1994 horror movie "Wes Craven's New Nightmare" was the seventh film in the "Nightmare on Elm Street" series, and featured one of the cleverest conceits for a horror sequel. The vicious supernatural serial killer Freddy Krueger — able to kill his victims from inside their dreams — somehow escaped the surly bounds of fiction and began stalking the actors and filmmakers who made the original "The Nightmare on Elm Street" a decade prior. Heather Langenkamp appears as herself, as does Robert Englund, John Saxon, Craven, and New Line Cinema bigwig Robert Shaye. Langenkamp did have a young child in 1994 — her late son Daniel Atticus Anderson was born in 1991 — but in the movie, Langenkamp's child was named Jacob and played by actor Miko Hughes.

Prior to "New Nightmare," the "Nightmare on Elm Street" series had become increasingly outlandish and cartoony. Freddy was no longer a menacing murderer, but a comedic supervillain who dispatched his victims in creative, unusual ways. Having complete dominion over the world of dreams, Freddy could turn his victims into cockroaches, flatten them into comic strips, wire them into motorcycles, place them inside video games, or make their heads explode with monstrous, ultra-powered hearing aids.

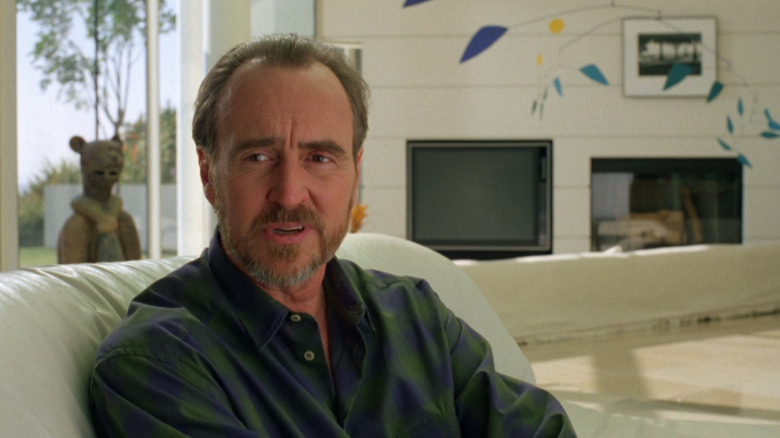

"Freddy's Dead: The Final Nightmare" was released in 1991, and that was thought to be it for the old Nightmare. It was Shaye who called Craven a few years after that, asking if it would be possible to squeeze at least one more film out of the franchise. In an interview with The Front, Craven admitted that revisiting Freddy would be apt in 1994, as he felt frustrated by the darkness he felt had been unleashed in the American psyche toward the end of the millennium. He wanted a Freddy story that reflected that.

The horrors of existence

When Shaye proposed a "Nightmare 7" to Craven, he said, "It came at a point of frustration." Shaye tasked the filmmaker with inventing concepts that might be adapted into film. A challenge, given the title of the previous movie. "We already killed Freddy Krueger," Craven said, "but he said there was an audience for one more. He asked if I could come up with an idea for Freddy to come back."

It's worth remembering that crime declined in the United States throughout the 1990s, and has been declining ever since. There was, however, a great deal of moral panic in the country, and some might recall the weird political furor over censorship. Tipper Gore notoriously helped create the Parental Advisory label, warning parents that labeled records might contain cuss words or sexual lyrics. Discussions were being had in earnest about the role of censorship in the modern world. Craven felt that censoring violent art would unleash violence in the real world. His idea for "New Nightmare" sprung from that notion. He said:

"We were in the middle of dealing with a lot of strict censorship. We asked ourselves what these films give or take away from culture. Do we really make kids go crazy and kill their baby sisters? It's like boot camp for the psyche. This is the way humans deal with the horrors of existence. If you forbid this kind of art, the actual real horror is unleashed in a sense. The way humans deal with the horrific is to put it in a narrative and cloak it in character. So by censorship and not being able to make any more films about Freddy, he will be unleashed. That was the concept that came out."

Without stories, Freddy is set free.

Theater of the absurd

"Wes Craven's New Nightmare" is tonally darker and far less humorous than the previous few films. Rather than make a straight-up horror movie, Craven longed to stretch into a post-modern milieu. He aimed to break the fourth wall, blurring the lines between what is fiction and reality. All his old actors would play themselves, and Freddy Krueger is even credited as himself. Craven, holder of a Masters in philosophy, was very pleased to delve into absurdism, as that was always the kind of literature that interested him. He also felt it was a fun, winking decision to include Robert Shaye in the film as well. As he explained:

"Smartest thing I said was that Bob would have a part in it and he liked that. I was steeped in 19th and 20th-century literature of the absurd, so it was in my intellectual bag. But in that time people had the same reactions as with 'Last House [on the Left],' fights in theaters and what have you. So I felt like, why not get past this fourth wall and talk about how music and art affects people ... and what about the people who make music and art and how it affects them?"

"The Last House on the Left" was Craven's first feature film, made in 1972. It's a bleak, grindhouse-friendly remake of Ingmar Bergman's 1960 film "The Virgin Spring." In both films, a young woman is out in the woods where she is accosted and murdered by passing criminals. The criminals then unknowingly seek shelter at the home of the girl's parents. Craven's film was brutal and widely criticized for its violence. The film was famously censored.

Craven, then, knew about the effects of censorship on art. Fitting that he should make Freddy get involved.