What These Iconic Horror Films Look Like Without Special Effects

Special effects artists are often the unsung heroes of horror films. Who is Pennywise without his startling clown makeup (above)? Who is M3gan without her hauntingly digitized face? Would King Kong and the silver screen's collection of other creatures and monsters even be remotely frightening without the technical prowess of the filmmakers behind their creation? We may not tangibly identify these artists' work in the moment as we watch a horror movie, but we certainly feel it.

On paper, many horror films' storylines don't seem scary at all; some even appear to be laughably unrealistic. Through special effects — practical mechanics, animation, makeup, puppetry, stunts, clever set-design tricks, and the like — artists can elevate even the most silly concepts into something macabre. They elicit the frights we love these movies for. Without them, such films appear quite different indeed. Here are what a few iconic horror films look like without special effects, in chronological release order.

King Kong (1933)

In the early days of filmmaking, artists' resources for creating movie magic were much more limited than today's supply of hat tricks. However, this fact doesn't render their work unimpressive. On the contrary, the wizardry that these creatives achieved nearly a century ago is all the more astonishing given the constant need to innovate in areas where no prior technology existed.

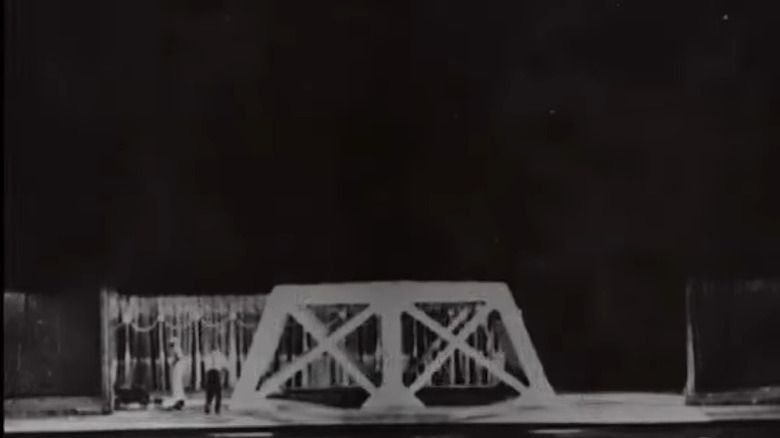

For example, in 1933's "King Kong," the namesake primate — a giant gorilla, much taller than any human — performs on a Broadway stage before a gathered audience. In real life, filmmakers captured this shot in two places. Inside the Shrine Theater in Los Angeles, the crew filmed a wide shot of an empty stage, void of any monster. Separately, stop-motion animators filmed a model of Kong on a miniature stage, to be supersized and imposed into the finished shot through a process known as matting.

It's natural for modern audiences accustomed to the special-effects spectacles of Marvel films to watch "King Kong" and wonder how audiences of 1933 considered the effect impressive at all. No one would blame them; by today's standards, Kong's appearance is inarguably archaic. Not that 1933 moviegoers believed they were seeing footage of an actual giant gorilla — but that the illusion, the wonderment of the scene's existence, still carried a whimsical mysticism as to how such an image could have been possible to composite.

Jaws (1975)

From the director's chair of 1975's "Jaws," a young Steven Spielberg enthralled audiences just as much with what he didn't show on camera as what he did show. The shark's elusive absence throughout most of the film is just as strong a horror device, if not stronger, than featuring the beast front and center every scene. The restraint in the shark's appearances — even if the strategy originated out of functional necessity, due to technical problems with the shark figure, rather than artistic intent — consequently meant that anytime Spielberg chose to spotlight a physical shark figure, the impact upon the audience was all the more menacing. In a way, among this list of what movies look like without special effects, the completed version of "Jaws" is basically already just that because Spielberg and his crew frequently couldn't use the special effect they planned for.

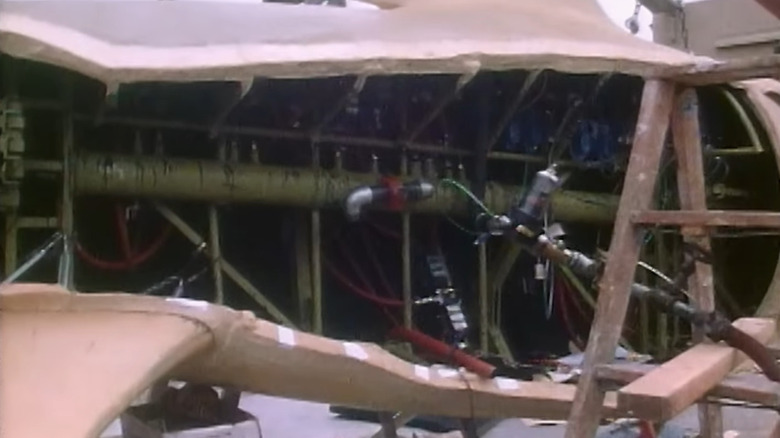

The shark doesn't seem quite as scary when he's on shore. Separate versions of him were fabricated to only be shown onscreen from one side. This meant the opposite side of the shark's body essentially provided a peek inside the robot's organs (pictured above), more fascinating than frightening. Bob Mattey designed the shark, coming out of retirement at the request of production designer Joe Alves. Mattey previously created the giant squid in 1954's "20,000 Leagues Under the Sea," Disney's adaptation of the Jules Verne novel. Though the shark figure's reliability on set was spotty, its brief screentime does a lot with a little.

An American Werewolf In London (1981)

A key ingredient in 1981's "An American Werewolf In London" is, well, the American werewolf in London. Creating the film's star character was a tall order tasked to makeup artist Rick Baker. In a home video bonus feature, Baker explained the process began as a creative conflict between himself and director John Landis. Baker wanted the werewolf to walk upright on two feet. Landis preferred the creature to walk four-legged. "He kept saying he wanted it to be this demon hound from Hell," Baker recalled.

This mandate, of course, would be harder to pull off onscreen. Baker's internal dialogue navigated the challenge: "How am I gonna do that? Can I put two people in a suit? No, that's gonna look dumb." The solution came to Baker in the middle of the night. He thought back to childhood wheelbarrow races, "where people hold your feet and you're walking on your hands."

Could a similar contortion of performers serve as a makeshift werewolf? Turns out, yes. Whenever the wolf performer suited up, they used their arms as the wolf's front limbs, the rest of their body lying parallel to the ground on a plank within the suit, their feet unceremoniously sticking out of the wolf's butt (off-camera, of course). The back of the suit emulated a wheelbarrow, able to be moved about by another person from behind. As the wolf walked, a puppeteer followed, operating the creature's hind legs with rods. Movie magic!

The Exorcist: The Version You've Never Seen (2000)

In 2000, Warner Bros. re-released 1973's "The Exorcist" with expanded sequences and unused scenes that landed on the cutting room floor in the horror film's initial run. Branded as "The Exorcist: The Version You've Never Seen," the extended movie included a moment in which Regan (portrayed in most of the movie by Linda Blair, but substituted by stunt double Ann Miles here) spider-walked backward down the staircase.

Back in the '70s, even with Miles' talented contortionist skills, she still required wires attached to her body to pull off the movement. Despite the filmmakers' best efforts, those cables were too visible on camera (as seen above). They distracted from the action and dispelled the illusion, so director William Friedkin removed the scene from the film's 1973 debut. By 2000, though, technology had advanced leaps and bounds. Making the wires invisible by means of computer-generated imagery (CGI) was more than doable. As such, Friedkin reinstated the spider-walk scene into "The Version You've Never Seen."

This trend fell in line with several other '70s and '80s classics re-released with updated technology around the dawn of the new millennium. George Lucas famously added CGI to the original "Star Wars" trilogy for its 1997 theatrical engagement, while Steven Spielberg similarly edited shots for the 20th anniversary of "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial" in 2002.

Friday the 13th (2009)

The team behind the 2009 reboot of 1980's "Friday the 13th" faced challenges typical of many Hollywood remakes, sequels, and spinoffs. How much of the source material should they retain in their retelling? Should anything be abridged, and if so, what, why, and how? In joining the project, director Marcus Nispel relayed an early instruction: "Create an underground — something claustrophobic, an old mine shaft, something like that — and have [the characters] operate from there," Nispel recalled in a home video bonus feature.

The tunnels get the job done. Enhancing the underlying eeriness of the story, the narrow passageways add an unsettling element to the aesthetic, even if their effect is subconscious. The audience feels the tension the tunnels elicit, even if they're not aware that that feeling is the tunnels' doing.

In real life, though, the underground labyrinth wasn't in close quarters after all. Set builders followed Nispel's wishes of creating claustrophobic pathways — 150 feet of them — but if the camera were to back up, the viewer would realize the tunnels existed in a large soundstage... just about one of the most open, expansive types of buildings one could imagine.

A Nightmare on Elm Street (2010)

With the technical finesse demonstrated by digital artists in the modern era, audiences enter a film with high expectations for visual effects. Benchmarks include Davy Jones' squid-like face in "Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest" and the sweeping vistas of Pandora in "Avatar." So, we've seen what's possible in terms of elite, believable computer-generated effects, and perhaps unfairly hold everything to those standards. Going hand in hand with this principle is the assumption that all special effects are digital. If anything onscreen could not exist in real life, it must have been created through the use of computer tools. Why wouldn't it be?

These natural, if baseless, preconceived notions about filmmaking are delightfully debunked by the perhaps surprising amount of practical effects that artists still use. In watching 2010's "A Nightmare on Elm Street," the audience might assume actor Jackie Earle Haley performed his role of Freddy Krueger makeup-less, with motion-capture dots covering his face to aid animators in monster-izing him in postproduction. While Haley wore a few small patches of green-screen-esque fabric for the purposes of visual effects — and the film contains its share of digital wizardry — Krueger's facial appearance was largely the work of talented makeup artists, led by makeup department head Karen Lynn. What you see on screen is what the crew saw on set.

Krampus (2015)

An oversized jack-in-the-box known as Der Klown serves as one of the sinister figures in 2015's "Krampus." Three artists brought the terrifying toy to life from within a multifaceted costume. Stunt performer Brett Beattie maneuvered the figure's head, puppeteer Imogen Stone the torso, and puppeteer Tanya Drewery the tail.

When it came time to film a stunt in which Der Klown violently careens through the air — starting in a living room, smashing through a window, and winding up 20 feet away in the snowy lawn outside — Beattie was the sole performer inside the clown suit. Furthermore, "outside" wasn't outside at all. The set existed within the more controlled environment of an indoor soundstage.

Stunt coordinator Rodney Cook helped build a ratchet to pull the jack-in-the-box out the window quickly. Cook had his work cut out for him, as he explained in a bonus clip posted to Universal's YouTube channel. "We're pulling something that's floppy," Cook said. "It's really long and it's a jack-in-the-box kind of thing. We had to get the torso through, get the tail through, and also get another body — flying on top of it — through." What projects as demented whimsy in the movie is, in actuality, intricate science and math at work.

The Nun (2018)

Creating a film requires artists of many trades and talents working together. The finished product as the audience perceives it wouldn't be what it is without the unique contribution of each individual department. Even with an accomplished actor giving a chilling performance as a horror icon... even with a skilled composer accentuating the scene with appropriately foreboding music... and even with a costume designer dressing the actor in a triumphantly nightmarish ensemble... it's often makeup artists who tip the scale in making cinema's most terrifying antagonists shine.

Such was the case when makeup department head Eleanor Sabaduquia transformed actor Bonnie Aarons into the namesake character in 2018's "The Nun." In a home video supplemental feature, Sabaduquia described Aarons's makeup design as being paler and employing a "gradation of grays" in contrast to how Aarons appeared at the beginning of each day's lengthy makeup application. A nun's wardrobe is universally recognizable enough to not necessarily need makeup to identify the central character. All the same, the makeup's presence elevates the foe's visual ensemble to be something more.

IT: Chapter Two (2019)

Would Margaret Hamilton have channeled the Wicked Witch of the West's signature cackle in "The Wizard of Oz" if she wasn't painted green and wearing a pointed hat? Would Ralph Fiennes have commanded scenes as Lord Voldemort if he didn't sport head prosthetics and wear billowing robes? In many cases, iconic makeup and costuming aren't just what we remember about a character; these elements help the actor inhabit the character to begin with. Taking these tools away poses a challenge, an acting exercise of sorts. Without the costume, without the makeup, is the character still there? Can the actor embody the personality all on their own?

While much of Bill Skarsgård's performance as Pennywise the Clown in 2019's "IT: Chapter Two" was achieved with practical makeup, director Andy Muschietti's plan for the film included Skarsgård performing a motion-capture test as the character prior to production commencing. This essentially distilled the character solely to Skarsgård's acting. Though the footage of him performing this screen test looks decidedly less creepy than Pennywise's appearance in the movie, Skarsgård's menacing smile, and therefore the spirit of Pennywise himself, remains present. Initially unsure of how effectively his motion-capture acting would go, Skarsgård reflected afterward, "Pennywise is ever-present and exploded out of me. I was surprised at how much of him was still there."

M3gan (2023)

The effective creepiness of the titular life-size doll in 2023's "M3gan" largely comes from the character's unsettling appearance of seeming almost real, but not quite. To achieve this, filmmakers approached the doll's performance as a combination of a live actor on set, Amie Donald, with animators in postproduction. Donald wore a wig cap during filming. Later, the digital artists superimposed M3gan's face and hair onto Donald's head, creating a character who moved like a real person but was visibly and obviously not human.

"I was really impressed with Amie's performance, especially because she was able to do most of the stunts on her own," said producer Jason Blum in a promotional video for the movie. Director Gerard Johnstone affirmed, "She could run on all fours really quickly. She could rise like a cobra without using her hands." Like many of the villains in our peek behind the curtain today, the M3gan character perhaps could have been created entirely with visual effects. The fact that filmmakers took a different, more practical path makes her place in movie history all the more memorable.