14 Times Star Trek Broke The Mold

The 1967 revision of the "Star Trek" writer's guide starts by asking the reader a simple question: "Can you find the major 'Star Trek' format error in the following 'teaser' from a story outline?"

"Star Trek" is a franchise that comes with many rules and dictums, many derived from its late creator, Gene Roddenberry. Other times they came from story editors and producers across the franchise's nearly-60-year history. And all of them are fiercely debated among fans in countless fanzines, convention halls, and chat boards, as well as on social media.

But rules are made to be broken, aren't they? Or, at the very least, broadly interpreted... like Starfleet's non-interference directive by some captains (looking at you, James T. Kirk and Jean-Luc Picard). And, to paraphrase Kirk, risk was "Star Trek's" business from day one. So let's look at 13 times when the makers of "Star Trek" took a risk and broke the mold.

1. Ron Jones went big and went home

Composer Ron Jones always seemed like an ill fit for "The Next Generation," reliably eschewing executive producer Rick Berman's preference for unobtrusive, low-key, musical scoring (dubbed "sonic wallpaper" by detractors). Senior composer Dennis McCarthy colored within the lines, while Jones effectively ignored them. Compare their scores for alternating episodes and decide for yourself which is the best of both worlds.

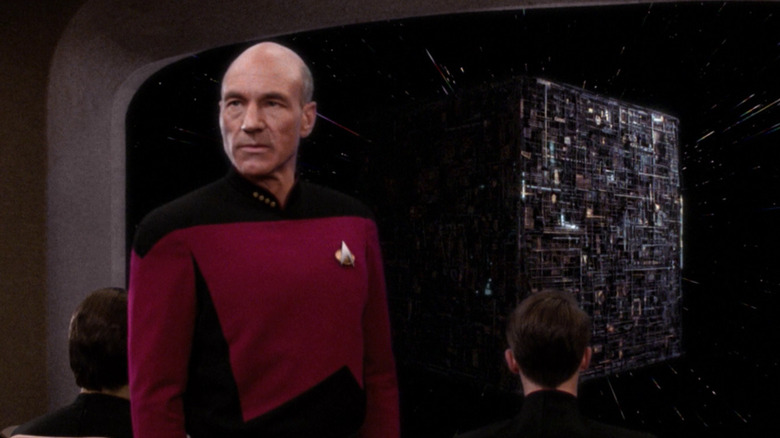

Speaking of which... Jones' tour de force score for the epic two-parter "The Best of Both Worlds" delivered motion-picture scale music that signaled the possible end of humankind as we know it. It even won the award for best soundtrack album of the year from the National Association of Independent Record Distributors (NAIRD).

But Jones' wont to go big (and reportedly over-budget) was ultimately doomed, and it doomed him. Berman dismissed him from "TNG" in Season 4, his final score being for the memorable episode "The Drumhead."

2. The Slaver Weapon ditched the show's star

Despite claims by the supporting cast, OG "Star Trek" was never an ensemble affair but rather a starring vehicle for William Shatner and breakout co-star Leonard Nimoy. From the second season on, DeForest Kelley shared co-star credit but firmly in third place. At various times, the show contracted most of the supporting players to appear in, say, eight out of 13 segments. Other times, George Takei and Nichelle Nichols were employed on a freelance basis. Poor Walter Koenig was always hired "as available."

"Trek" creator Gene Roddenberry's memos make plain that Kirk and Spock are the stars, and that they must drive the action. "This Side of Paradise" initially featured a romance for Sulu (Takei) but that big story point soon went to Spock. The only time Kirk ever took the back seat? When he vanished into the "spatial interphase" in "The Tholian Web." Even then, however, the story focused on Spock risking everything to rescue him.

The 1973 animated "Star Trek" followed this rule closely: except once. The episode "The Slaver Weapon" doesn't feature Kirk at all (outside the opening titles' voiceover). And no Enterprise, either! This is because the story was a barely altered version of SF author Larry Niven's short story "The Soft Weapon"; and he simply swapped the closest "Trek" equivalents for his own "Known Space" universe characters.

3. Absolutely no Spock siblings

Kirk: You mean he's your "brother" brother? You made that up.

Spock: I did not.

Spock may not have made that up, but rule-breaker William Shatner and co-writer David Loughery sure did for "Star Trek V: The Final Frontier." The film gave us the first of Spock's previously never-mentioned siblings: his half-brother, Sybok. Decades later, "Star Trek: Discovery" introduced Spock's adoptive human sister, Michael Burnham, the only child Spock's father, Sarek, actually got along with.

But at the start of OG "Trek's" second season, then-story editor Dorothy (D.C.) Fontana made Spock's family situation very plain. Writing to the fanzine Spockanalia, she explained, "Both his mother and father have been married only once to each other. Spock is an only child... There are absolutely no other siblings."

One can get sneaky around this "married only once" rule by saying Sarek never married Sybok's mother, and that Burnham was adopted. Both cases break Fontana's firm "absolutely no other siblings" edict.

4. Technobabble breaks a cardinal rule

If your "Star Trek" watching began with "The Next Generation" you'll be familiar with the jargon-laden dialogue most commonly spouted by Data and Geordi La Forge. Such doubletalk peaked under the tenure of executive producer Michael Piller; so much so that actor Brent Spiner (Data) dubbed it "Piller-Filler." And filler it was. "The technobabble in Trek just got completely out of control," writer-producer Ronald D. Moore confessed, "The actors hated it." The show had science consultants who would come up with the words for the writers, who would just write 'tech' in the script." Hard SF author Charles Stross derided this as having "thrown away the key tool that makes SF interesting and useful in the first place, by relegating 'tech' to a token afterthought."

Ironic, since such technobabble was verboten under Roddenberry's watch. In the OG series and movies with its cast, there's an almost complete lack of "Piller-Filler."

"Joe Friday doesn't stop to explain the mechanics of his .38 before he uses it," was advice given to writers, as reprinted in the book "The Making of Star Trek." So, how much science-fiction terminology should scripts contain? The "Star Trek" writers' guide cautioned, "the minimum which is sufficient to maintain the flavor of the show and encourage believability[...] however, the writer must know what he means when he uses sf terminology. A scattergun confusion of meaningless phrases only detracts from believability."

Sadly, this rule got broken more times than not over multiple series.

5. Recasting legacy characters

Of his abandoned "Trek" project in 1977, director Philip Kaufman said of the cast, "They were going to play more of a minor role. I was going to put them in the background." Roddenberry always resisted such attempts, just as he resisted replacing the Enterprise with something radically different. And thus we got the big reunions that were the movies "I"–"VI." Any time a recurring actor left the show their part was never re-cast. In fact, the only significant recast for decades was replacing Kirstie Alley with Robin Curtis as Saavik for "Star Trek III", but that wasn't a legacy role. Producer Harve Bennett's "Star Trek: The First Adventure" script featured Kirk-Spock-and-company-as-cadets, and he had an eye on John Cusack for Spock and Ethan Hawke for Kirk. But that script was shelved in favor of "Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country."

So there had never been a complete recast of the OG crew until J.J. Abrams' soft reboot "Star Trek" (2009). It's something that's been carried over with "Discovery" and now "Strange New Worlds." To date, we've seen Kirk, Spock, Uhura, Scotty, and Pike played by three different actors each, and McCoy, Chekov, Chapel, M'Benga, and Number One each played by two.

Thank the Great Bird of the Galaxy (Roddenberry) for that. Could you imagine a necro-CGI Nimoy on "Discovery" or "Strange New Worlds"? Mark Hamill nailed it... recast, not reanimate.

6. Pulitzer-winning writer ignores Roddenberry's no money utopia

Gillian Taylor's (Katherine Hicks) banter with Admiral Kirk (William Shatner) over a dinner bill in "The Voyage Home" firmly established "Trek's" economics no longer used money; something Captain Picard reiterated to Lily Sloane (Alfre Woodard) in "First Contact," adding "humanity works to better itself."

But Season 1 of "Picard" depicts a Federation that doesn't feel free of the capitalistic shackles of money. It's certainly not Roddenberry's Post-Scarcity socialist utopia. Picard is of the landed gentry, living it up in his chateau, making his family's wine with farm hands he employs. Meanwhile, his former colleague, Raffi Musiker (Michelle Hurd), lives in a trailer with no social support for her vices.

On Instagram, then-showrunner and Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Michael Chabon addressed this discrepancy. He wrote that "Trek's" no-money society is "interesting and even provocative in pockets but highly unsatisfying overall." As to Raffi's situation, he said that for someone "who is determined to hit bottom, no safety net will ever be sufficient."

"Strange New Worlds" has re-embraced the concept of the moneyless utopia with Pelia (Carol Kane) stating she hoards just in case "this no money, socialist utopia is a fad."

7. Starfleet as a military organization

"Scientists have always been pawns of the military," cried Dr. David Marcus in "The Wrath of Khan," the first installment in the franchise which did indeed treat Starfleet as a more overtly military organization than it had ever been previously portrayed in the original and animated series and "The Motion Picture," and beyond what creator Gene Roddenberry wanted or intended. Even as the OG series was in production, he characterized the service as a "quasi-military" organization; like a hybrid of NASA and the Coast Guard, where — like astronauts — everyone was an officer. No saluting, piping in, or tedious "Captain on the bridge"-ing.

But when Paramount granted him creative control of "The Next Generation," Roddenberry firmly slammed the lid on the harder military take for "Trek." And thus it remained until his death. The military-mindedness crept back in over the years, particularly in the Dominion War of "Deep Space Nine" and the Xindi arc on "Enterprise." Shows like "Strange New Worlds," however, have largely chosen to reattach the "quasi-" to the "military," re-embracing Roddenberry's rule after it's been battered, bent, and broken.

8. Section 31 breaks almost all of Roddenberry's ideals

If Roddenberry hadn't been cremated, he'd be spinning in his grave over "Deep Space Nine's" invention of the extra-governmental agency Section 31 — and the fact that no one dismantled it.

Roddenberry wasn't as starry-eyed as popularly portrayed. His later works, like "Genesis II," and even some details in early "TNG" ("the post-atomic horror") demonstrate that. He thought humanity might have to come close to destroying itself before getting its act together and growing up. But, that was in "Trek's" past. The occasional bad actor or bad admiral aside, he considered the Federation as a whole and Starfleet as pretty upstanding — if bureaucratic — organizations; and nixed Starfleet personnel deliberately undermining the organization for "TNG's" episode "Conspiracy." This carried through the shows produced after his death and became a sticking point in the scripting of the movie "Insurrection." As Piller explained in his unpublished memoir, "Fade In: The Making of Star Trek — Insurrection," Berman resisted attempts to make the Federation knowingly complicit in stealing a planet from its inhabitants.

An autonomous organization answerable to no one was anathema to Roddenberry's vision for "Star Trek." The notion that any branch of the Federation or Starfleet would attempt genocide, as portrayed in "DS9," would have never gotten past his desk.

9. Enterprise boarded the story arc

The original "Star Trek" was invented to be episodic. That's baked into the earliest conception of the show: a "Wagon Train to the stars," where the regular characters encounter guest stars and get involved in their stories, then move on.

That was the status quo for almost 30 years. Until "Deep Space Nine," no "Trek" had been significantly serialized, and even that series was mostly episodic, with the Dominion War representing its longest sustained arc. Not until "Star Trek: Enterprise" did the franchise boldly go for a season-long arc with a clearly delineated beginning and end.

In the third season of that show, Earth was attacked, and the NX-01 Enterprise embarked on a desperate mission into the unknown. Its goal was to locate the source of the attack and thwart an even more devastating one. This event signified uncharted territory for "Trek." Despite occasional execution that fell short of expectations, it introduced a format shift uncommon in the conservative Berman-era "Trek" shows. Consequently, it established the groundwork for the serialized streaming-era franchise series that would emerge more than a decade later.

10. It's all about the people, people

Freelance writers for the original "Star Trek" often got lost in "the wonder of it all" of their sci-fi scenarios. They wrote the regular characters as passive, which is "Star Trek—The Motion Picture" in a nutshell.

One of the biggest complaints about the film is the long stretches where the crew gapes at alien vistas. Those stretches helped earn the film an amusing nickname: "The Motionless Picture." But during the making of OG "Star Trek," Roddenberry frequently cautioned those freelancers about the importance of having the main characters drive the action. Funny that the only Roddenberry-produced movie would be criticized for its passivity and lack of humanity.

The second feature film returned to stories about the characters. In "The Next Generation," Piller's rule was that the stories should involve and personally affect the characters. But on "Voyager," a Rick Berman dictum decreed that the actors playing humans should underplay their roles, according to actor Garrett Wang (Harry Kim). But full humanity once again returned to "Trek" in its current era with "Star Trek: Discovery."

11. These are the non-voyages

Paramount sought to capitalize on the syndication success of "The Next Generation" with a spin-off. It tasked "TNG's" Berman and Piller with creating the new show. They came up with a twist. If the original series was "Wagon Train to the Stars," this new show was "The Rifleman in Space." That series focused on a Civil War vet and widower and his young son living on the frontier. Their proposal would take a page from that playbook but set the scene on an outpost at the edge of the final frontier.

"These are the voyages..." is so tied up with "Trek" that the idea of this third live-action series ditching a starship for a space station was a major break with the past. This station was located near a stable wormhole. The name of the place... Babyl... wait, sorry that's not right. I meant Deep Space 9; a former Cardassian mining station orbiting the planet Bajor, and now operated by Starfleet to help the planet join the Federation. Maybe.

What of the similarities between "Deep Space Nine" and another space station show? "Babylon 5" creator J. Michael Straczynski said he's confident Piller and Berman didn't know about his series even though he had originally pitched it to Paramount.

12. Breaking out in song

Musically, when you think of the franchise, you think orchestral scoring, and the most controversial theme song was a pop ballad. So when "Strange New Worlds" went Broadway for "Subspace Rhapsody," it managed the neat trick of breaking the rules for "Trek's" format while simultaneously telling a tale in keeping with the 600-plus hours of "Trek" preceding it.

It had the USS Enterprise's crew singing and dancing. It featured a Klingon boy band. The Enterprise performed choreography with Klingon battlecruisers. It even changed up the theme song.

As big a franchise change-up as this was, it was timidly going where many other shows went before. Musical episodes abounded in the 90s, including on "Northern Exposure" (in 1993), "Chicago Hope" (in 1997), "Xena: Warrior Princess" (in 1998), "Ally McBeal" (in 2000), and "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" (in 2001). Groundbreaking for "Trek," yes, but a quarter century behind the curve.

13. Voyager broke its entire premise

Paramount launched a fifth U.S. television network in 1995, and headlined it with a "Star Trek" show, much like their original plans for a fourth network in the late 1970s. "Star Trek: Voyager" did something no other show had done previously — strand a titular starship many years travel from Earth. Originally, the ship was to be a powder keg. Its stalwart Starfleet crew and a band of renegades, known as the Maquis, work together to survive being lost in space (to coin a phrase).

"Deep Space Nine" had introduced the Maquis as a freedom fighter-terrorist group made up of former Starfleet and Federation citizens. Captain Janeway of the starship Voyager tracked down the rebels, but both her ship and the Maquis' wind up whisked away to the farthest end of the Milky Way.

While "DS9" featured more interpersonal conflict than allowed under Roddenberry's rules on "TNG," the "Voyager" premise seemed meant to push that to the limit. But the show broke with its own core premise almost immediately, ditching the dramatic conflict between the two groups as early as episode two. Except for one or two episodes where the division comes up, the Voyager becomes just one big, happy crew. In his unpublished memoir, Piller wrote that this decision to curb the conflict was predicated on the most common criticism of "DS9": fans didn't want to see the "family" fight.

14. Frakes broke the house rules for The Drumhead

Outside the realm of visual effects, where it was cutting-edge TV at the time, "The Next Generation" wasn't terribly innovative in terms of its direction and cinematography. Even in its heyday, it felt almost quaintly old-fashioned compared to shows that preceded it, like "Hill Street Blues" or "Miami Vice." For his third outing as director of a "TNG" segment, Jonathan Frakes decided to break a big rule in the way he handled the episode "The Drumhead".

"TNG" developed a simple and editor-friendly house style imposed under the auspices of executive producer Rick Berman. But Frakes wished to be more dynamic in his visuals for this episode, especially since it boasted an illustrious guest star: Jean Simmons. It featured inventive camerawork for "TNG," moving around the sets, darting high and low, and lingering on characters rather than cutting constantly.

At the time, Frakes had two well-received episodes under his directorial belt, so he was in a good position to get more leeway for shooting outside the "TNG" box. That he was the show's second-highest-billed actor didn't hurt! And it all led to a full-on, decades-long second career for Frakes as a director of "Trek" shows and movies, as well as a wide variety of non-"Trek" projects.