Rod Serling's Big Twilight Zone Pet Peeve Is Still As Frustrating As Ever

Although he had a career in theatre, radio, and feature films, writer/producer Rod Serling's legacy is inexorably tied to the medium of television. That's for very good reason, of course: not only did Serling create multiple television series that has withstood the test of time (such as "Night Gallery"), but he also was responsible for shaping a good deal about television as we've come to know it. For instance, the teleplay he wrote for an episode of "Kraft Television Theatre" entitled "Patterns" was so popular that the series decided to rebroadcast it in its entirety, thereby creating the concept of the "rerun."

As such, Serling was deeply entrenched in the rise of television, and that meant having to deal with growing pains and emerging annoyances. In order to continue experimenting with the form of TV and pushing the envelope of what types of stories could feature there, Serling found himself having to suffer the demands of advertising. Where early live television series had a less intrusive, smoother way of inserting ads into their programming (in a format adopted from the way such things were handled on radio broadcasts), pre-filmed programs had to deal with one and, later, several commercial breaks. In the case of "The Twilight Zone," Serling found these commercials to be increasingly detrimental, especially with regards to attempting to establish a distinct tone and retain an audience's suspension of disbelief. It's a pet peeve of the writer that is still a problem for television (and now streaming services) to this day.

Serling vs. '12 dancing rabbits with toilet paper'

Selling "The Twilight Zone" was not an easy task for Rod Serling. The concept of anthologies had more or less been introduced to TV via long-running radio programs like "Suspense" and "X Minus One." There also already existed "one-and-done" live shows like "Kraft Playhouse Theatre," "Playhouse 90," and so on. Yet "Twilight Zone" purported to be a genre anthology show that was to emulate emerging trends in science-fiction and horror seen in literary circles (primarily the works of writers like Ray Bradbury, Charles Beaumont, and Richard Matheson, all of whom worked on the series) at a time when filmed genre entertainment skewed more toward the hokier realm of Atomic Age aliens and giant monsters.

Serling knew that convincing the higher-ups at CBS was only half the battle; he'd have to win over audiences, too, and that struggle would be compounded by the scourge of tone-killing commercial breaks. As Serling ruminated while speaking at UCLA on May 17th of 1971:

"... [H]owever moving and however probing and incisive the drama, [a show] cannot retain any consistent thread of legitimacy when, after 12 or 13 minutes, out comes 12 dancing rabbits with toilet paper. It puts the creator, particularly the writer, in a tough emotional bind, though, because obviously Sanka coffee, here, as tasteless and offensive as those commercials were, nonetheless paid the freight. How do you predatorily bite that hand that feeds you consistently?"

Serling's ultimate victory

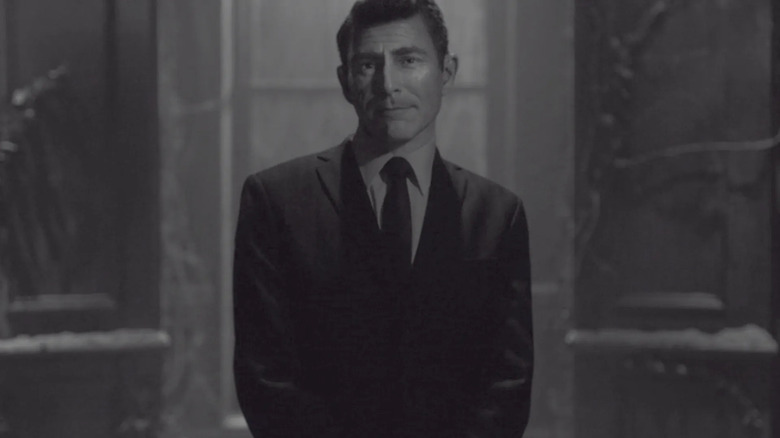

When taking Serling's feelings on commercials into account, the establishment of what would become his signature aesthetic starts to become a little clearer. As he said, his primary concern about commercial interruptions was keeping viewers immersed in the story. To help combat this, he took the unusual step of narrating the episodes of "Twilight Zone" himself during the show's first season (after first exploring someone else), creating a literal framework that broke the fourth wall while still retaining the theme and tone each episode hoped to create. This tactic went even further during the second season and beyond, involving Serling literally stepping into the episodes to deliver his opening narration, a style that continued and developed further during "Night Gallery."

While reruns of "Twilight Zone" in syndication are still subject to commercial breaks (leaving some episodes truncated from their original broadcast length), Serling would most likely be happy with the advent of streaming services, which remove ads from the viewing experience entirely. At least, up until now, as the streaming world is currently shifting and mutating into a form that is increasingly resembling classic cable television, complete with the return of ad interruptions.

Fortunately for us viewers and Serling, physical media remains blissfully ad-free. The "Twilight Zone" Blu-ray sets, in fact, do Serling's wishes one better: where each episode has been lovingly remastered with the original bumpers, next episode previews and post-episode ad spots included, the only thing omitted are the commercial breaks from the episode's sponsors. Those commercials are still included in the special features menu for each episode, they just aren't part of the full episode when viewed. All of which is to say that the Blu-ray producers took Serling's feelings to heart, removing all commercial interruption and allowing each show to create its full, intended emotional impact. Let's hope that some similar solution is found by streaming services — and maybe even broadcast TV — going forward.