Guy Ritchie's The Covenant Review: A Shallow War Movie About Bros Standing Up For Each Other

Filmmaker Guy Ritchie's filmography is, like Sam Peckinpah before him, replete with assertive, unabashed maleness. With the possible exception of "Aladdin," Ritchie's films hover on the concerns of dudes being dudes, usually bonding over their mutual passions for criminality and violence. When he makes gangster movies, he's careful to include multiple scenes of his characters hanging out, chatting, and generally enjoying being blokes. His spies and detectives tended to be obsessed with fashionably outshining the men closest to them. Femaleness is rarely Ritichie's focus, as he lives in the realm of lager louts. Even his Arthurian movie, the legendary bomb "King Arthur: Legend of the Sword," featured a scene wherein the title monarch reveals his famous Round Table to his beer-drinking knights. "It's a table," he said. "You sit at it." Actual warmth and tender emotions aren't to be much expected from Ritchie's protagonists.

It's curious, then, that it has taken him so long to reach the world of soldiers. In Ritchie's newest film, "Guy Ritchie's The Covenant," a pair of men, bound together by a mission in 2013 Afghanistan and by mutual regard for their respective military skills, take turns rescuing each other from certain death. While pro-military and jingoistic in its construct, "The Covenant" is far more concerned with how much bros — real bros — stand up for one another. The American military is ideal for a man interested in tales of uncut masculinity. This is a world where male friendship is necessarily marked by violence, death, and a flip "Yeah, I did that" attitude. It may not bear the wild style of most of Ritchie's other movies, but it bears all his thematic hallmarks.

Do one for me, bro

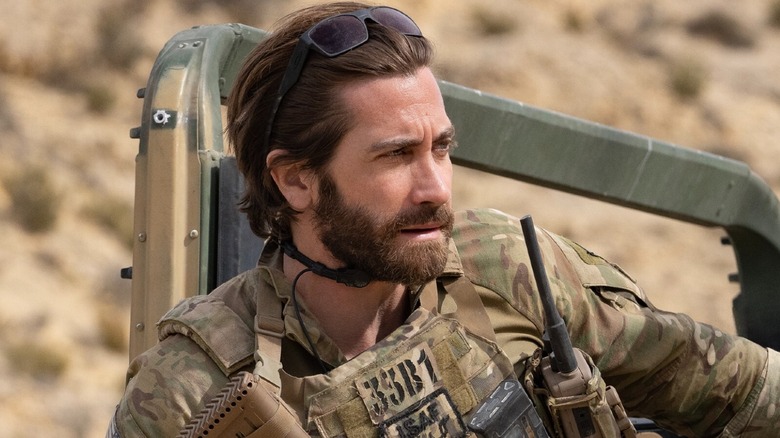

Jake Gyllenhaal plays U.S. Army Sergeant John Kinley who, during the 20-year-long war in Afghanistan, was tasked with tracking down the Taliban's bomb-making sites. Because none of the American soldiers speak the local languages, they require an interpreter. Because the mission is so dangerous, it would help if their interpreter was also trained in a certain degree of military tactics. Kinley is paired with Ahmed (Dar Salim) a former drug kingpin who hopes, by working with the U.S. military, to obtain an exit visa and flee the country. As a film-end chyron explains, the military promised many, many such visas, although it seems they rarely made good.

The first half of "The Covenant" is about Ahmed and Kinley locating a Taliban base and the ensuing, prolonged firefight that resulted from the discovery. Kinley is injured, and the two have to trek through the wilderness, avoiding Bad Guys and working their way to safety. Ahmed, through a sense of soldierly obligation, keeps Kinley alive through some rather harrowing circumstances, including dragging him bodily up a mountain, "Fitzcarraldo" style. The rescue, once completed, becomes a folk tale among the Taliban, leaving Ahmed vulnerable to the regime. The second half of the film, set about a year later, will see Kinley leaving his family behind in the U.S. and returning to Afghanistan to rescue his rescuer. You do one for me, bro, and I do one for you. It's a Covenant. You sit at it.

"The Covenant" is about how masculine, soldierly regard is desirous and self-evident. If two men are equally capable of killing for one another, then kill they shall. The actual circumstances of their being in danger — the politics of the war itself — are not to be litigated.

The non-litigation of war

In terms of raw, visceral thrills, "The Covenant" is functional and exciting. Ritichie's forthright, slick, brutal skills as a director of shootouts are on full display here; unlike many modern action filmmakers, Ritchie retains a good sense of spatial continuity in his firefights. When Gyllenhaal and Salim are sliding down dangerous slopes or trekking up rocky terrains, one always knows where the enemy soldiers are in relation to them. In action films, and in war films in particular, clarity is key. If one is to see "The Covenant" as merely an action film, then it certainly delivers.

However, there is a great deal missing from Ritchie's film. "The Covenant" is almost aggressive in its complete lack of wartime litigation. While the harrowing nature of a soldier's experience is laid bare, the meaning of the actual, prolonged quagmire of the Afghanistan occupation will be lingering in the back of most audience's minds. There's no talk about why the soldiers are there, and few mention that there doesn't really seem to be a way to win this war. After so many years, one might think that the soldiers would be hollowed out, dismayed, trapped in an endless, Sisyphusian struggle. Instead, they are seen as held upright by their bro-ness. It's telling that one of the new members of Kinley's platoon is welcomed to the fold with a can of American beer. For these characters, all nicknamed like in a boys' clubhouse, a cold one and a fist-bump are where their existence begins and ends.

Also unlitigated is the imbalance of what's at stake for Kinley and for Ahmed. A moment's thought proves this to be a sizeable issue.

Look away from the quagmire

For Kinley, he is merely an occupying soldier, following orders and gaining accolades for violence. His boss (Jonny Lee Miller) praises his abilities. His only personal dangers seem to be career oriented. When Kinley calls his wife (Emily Beecham), she is endlessly supportive, despite his prolonged absence and nearness to death. Ahmed, meanwhile, is in constant danger. The locals hate him for collaborating with the U.S. military, and he only takes the money to support his wife and infant child. Ahmed's story is clearly the more interesting one. Why did we have to focus on Kinley at all?

It seems galling for Hollywood to make a story about a struggling Afghani interpreter, and somehow foreground the American soldier in his place. See also: John Woo's "Windtalkers," a film about a WWII code-translating Navajo soldier ... being protected by a brave white dude (in that case, Nicolas Cage).

Salim, however, gives Ahmed a great deal of humanity, refusing the play the character as anything other than capable and resolute. Salim, a Danish actor, outshines his co-star by a considerable margin, communicating intelligence and humanity through the manly grit that Guy Ritchie shoulders him with. The sequences where the Gyllenhaal character is taken out of commission, and Salim has to use his wits to survive may make audiences wonder why the film was told from Gyllenhaal's perspective.

The final chyron pointed out that, after the U.S. hastily withdrew from Afghanistan in 2021, the Taliban immediately regained power over the government. The quagmire was futile. "The Covenant" is not an Oliver Stone-like damnation of the war experience. For Ritchie, war is quite grand, and a great way for dudes to get to know each other. On that shallow level, I suppose it functions. Beyond that, it may disappoint.

/Film Rating: 5 out of 10