Why You Should Watch Naked Lunch, David Cronenberg's Most Baffling Film

To celebrate David Cronenberg's 80th birthday, check out his underrated adaptation of the controversial novel "Naked Lunch."

David Cronenberg, the undisputed king of cinematic body horror, turns 80 this month, and he shows no signs of slowing down. Last year, with the release of "Crimes of the Future," he heartily reminded audiences that there's no filmmaker greater than he when it comes to piercing dissections (often literally) of the human form's grotesqueries and its relationship with the wider world. He's so distinctive, so unflinching in his portrayal of that which horrifies us most, that we use the adjective Cronenbergian to describe works inspired by him. Every fan of Cronenberg has their favorite moments from his vast filmography, whether it's the exploding head in "Scanners," Jeff Goldblum's disintegration in "The Fly," or the abnormal births in "The Brood." One of his lesser-discussed films, and perhaps his most curious effort as a director, is just as gross as his most iconic work but was so unexpected to many of his devotees that it sank under the radar for years.

His first film after "Dead Ringers", which signaled a new peak of critical adoration for the director, Cronenberg's "Naked Lunch" seemed like a project doomed to sink at the box office. How do you adapt a demented novel that's notoriously difficult to read, and do so while retaining its depictions of drugs, sexual abuse, murder, and bodily orifices? And how do you manage it under the helm of a major studio, 20th Century Fox, with hopes of a wide release across the globe? Somehow, Cronenberg pulled it off, but it flopped, garnering only $2.6 million out of a $17–18 million budget. This scared the studio, as audiences just didn't seem ready for "Naked Lunch", although it did win a ton of Genie Awards in Cronenberg's native Canada. Nowadays, its reputation has fared better with critics, and a Criterion Collection release has secured its status in the Cronenberg canon, but it remains one of his least-seen films. That should change, because it's easily one of his most challenging projects, and maybe his most baffling.

Naked Lunch is controversial and unadaptable

In 1959, the American author William S. Burroughs released "Naked Lunch", a surreal and stark novel inspired by his experiences with drug addiction. It's a tough book to read, a loosely connected series of vignettes that can be read in any order, conveying the mind-splitting terror of substance abuse and paranoia. Hugely controversial upon release, it was initially banned in several American cities, deemed obscene by the U.S. Post Office, and inspired walk-outs at universities. It's a fool's errand to try and describe what the book is about, and its most infamous moments include child murder, acts of pedophilia, and a talking a**hole. "Naked Lunch", on its surface, seems to be the epitome of an unadaptable novel. So, of course, David Cronenberg managed to adapt it.

Cronenberg's status as an adapter of tough material is oft-overlooked. This is the man, after all, who brought "Crash" to the big screen; a book often as clinical and impenetrable as "Naked Lunch." With Burroughs' book, he made the savvy decision to bring in other elements of Burroughs' work as well as autobiographical accounts of his life. Infamously, Burroughs shot and killed his partner Joan Vollmer during a drunken game of William Tell. He was later convicted in absentia of homicide and sentenced to two years, which were suspended. He would later admit that her death played a crucial part in kickstarting his career as an author, saying, "I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would have never become a writer but for Joan's death."

How Cronenberg adapted Naked Lunch

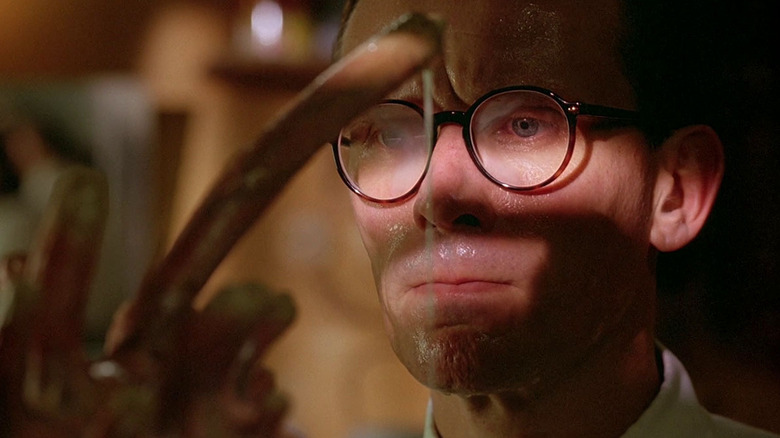

Joan Vollmer's death was written into Cronenberg's "Naked Lunch", serving as the impetus to a somewhat more conventional narrative that's present in the novel, but often seems inconsequential to William Burroughs' wider intentions. The protagonist is William Lee, played by Robocop himself, Peter Weller. He's an exterminator whose wife, Joan, played by Judy Davis in one of her best performances, has gotten hooked on the insecticide he uses for work. Like Burroughs and Vollmer, Lee accidentally kills Joan in a game of William Tell, attempting to shoot a whiskey glass from atop her head. But it may also have been a deliberate assassination, as ordered by a giant talking beetle who claims that Joan was a secret agent working with a shady organization based in the Interzone, somewhere in North Africa. After Lee flees, he tries to write reports on his escapades, all while sinking further into addiction and becoming embroiled with another writer and his wife who looks exactly like Joan (and is also played by Davis). Are you keeping up with this?

While there's a more cohesive narrative to Cronenberg's film than Burroughs' novel, neither prizes the kind of closure or easy answers a traditional cinematic arc would present. The idea is to replicate the unique strain of mania that comes with hard opioid addiction. Lee ingests bug spray, a yellowish powder that seems like a stand-in for heroin, and its side effects include a total disengagement from the truth. Is Lee actually a secret agent? Is he really in North Africa with a talking typewriter that gives him orders? Are mugwumps real? The answers seem evident given Lee's state, but Cronenberg is uninterested in pointing out the obvious — not when his own protagonist can't see it.

What's With All the Bugs?

It famously irked Nelson in "The Simpsons" that there was no nakedness or lunch in "Naked Lunch", but there is plenty of consumption of another kind. Burroughs was a leading figure of the Beat Generation, a movement of writers who sought to dismantle the rigid norms of post-war American culture. Alongside writers like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsburg, Burroughs tore into the staid social demands of their era, challenging the literary norms as well as societal ones. That led to a lot of outrage from the law and even a few obscenity trials thanks to their proclivities for stark depictions of sex, violence, and drug use. Nothing is off the table in Burroughs' work, but translating that to the big screen, in a studio film no less, gave Cronenberg a few challenges.

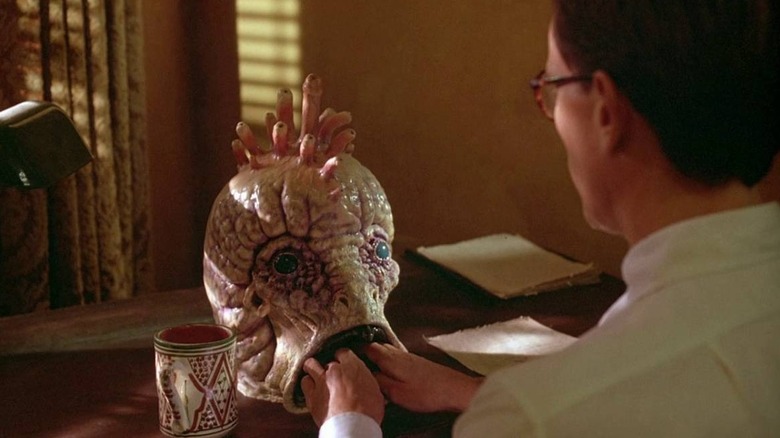

The grotesque nature of Burroughs' work, so stripped of optimism and sentimentality, takes physical form via Cronenberg's creatures. Lee's typewriter is a talking bug that groans with pleasure when typed upon, and demands that bug powder be rubbed on the "lips" of his anus-like back. Lee casually encounters a mugwump in a bar, a human-sized alienesque figure with protruding sphincters that leak addictive substances (which we later see people milking in a drug den for personal use.) All of this is shown with a cool detachment, not quite as clinically as Cronenberg manages with "Crash," but so matter-of-fact that you too are pulled into the absurdity of Lee's addled world. Why wouldn't bugs tell you to kill your wife? Lee, with Weller's monotone dry wit, addresses such things as if he's in line for the bank. As Burroughs' novel famously says, exterminate all rational thought. Like a bug.

How Naked Lunch depicts addiction

It's fascinating how "Naked Lunch" is unlike other portrayals of drug addiction. This is no "Requiem for a Dream," where the degradation of the human form is revealed in agonizing detail. We don't see Lee get high, so to speak. Everyone takes the bug powder in a curiously straightforward manner and nobody is shown strung out or in the midst of a trip. The truth of Lee's time in the Interzone is only revealed when a few friends find him wandering destitute through the city, with a pillowcase full of paraphernalia, of which he seems entirely unaware. This isn't what one would expect from the director of "Scanners." Cronenberg is not one to shy away from the rot of flesh, so when he does restrain himself on such fronts, you know he's doing it for a reason. In "Naked Lunch", mental rot is as horrifying as that of our tender, fragile bodies.

Burroughs was remarkably candid in discussing how his various troubles influenced his now-iconic output as an author. Reading his work makes one highly aware of Burroughs' creative origins, particularly the death of Vollmer, which is given immense focus in Cronenberg's adaptation. Becoming a writer is an act of self-annihilation for both Lee and Burroughs. There's no joy in what he's been through, not when so many were damaged in the process. In this sense, Burroughs found the ideal bedfellow in Cronenberg; a creative who often views the act of creation with a kind of nonplussed horror. By the end of their "Naked Lunch", Lee/Burroughs is now officially a writer, but it barely seems worth it. The Interzone will eat you alive.