Orson Welles' Favorite Film Idea Was Ruined In The Editing Room

Auteurs and Hollywood don't always mix. Stanley Kubrick put some considerable distance between himself and the studio system after being required to stick closely to Dalton Trumbo's "Spartacus" script in 1960 — heading to England to secure funding and creative control on 1962's "Lolita." But he wasn't the first American filmmaker to flee his homeland in search of artistic freedom and funding.

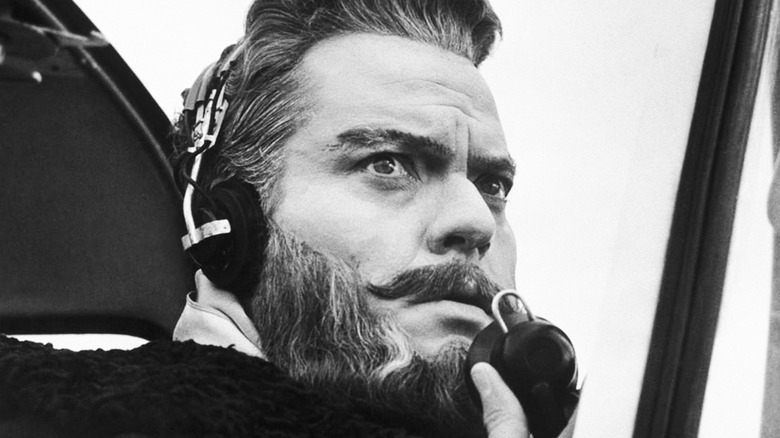

Orson Welles is perhaps the ultimate example of a director clashing with a filmmaking industry unaligned with his sophisticated artistic ambitions. After his first film, "Citizen Kane," debuted in 1941 and proved a financial failure, Welles had to fight for financing and artistic control on future projects. RKO, which had funded "Citizen Kane," renegotiated Welles' contract to remove the unprecedented creative control he was initially afforded. And even though the film would eventually become regarded as one of, if not the finest movie ever made, the director would regularly find himself at odds with producers throughout the remainder of his career. As he told the BBC in 1982: "The people who have done well in the system are the people [...] who want to make the kind of movie which producers want to produce."

Welles did not include himself in that group. After "Citizen Kane" flopped on its initial release, his follow-up, "The Magnificent Ambersons," was recut and reshot at the behest of RKO, before his next project, "It's All True," was canceled outright. Welles would endure more frustration when Columbia Pictures head Harry Cohn forced him to recut his 1948 effort "The Lady from Shanghai," which lost Columbia half a million dollars. Soon after that, Welles turned to Europe, where he made and starred in multiple films. But his creative control woes would follow him, leading to what he saw as the biggest disaster of his career.

The multiple versions of Mr. Arkadin

Orson Welles always had specific ideas about how his films should be edited. He wrote a 58-page memo to Universal making shot-by-shot suggestions on how to cut together his 1958 movie "Touch of Evil," which the studio outright disregarded. But the biggest editing debacle of his entire career came with his 1955 effort "Mr. Arkadin."

Written and directed by Welles, who also starred as the titular billionaire, "Mr. Arkadin" was envisioned as a series of intricate flashbacks that reveal the plot's various twists and turns. The narrative follows one of Orson Welles' best characters, Russian Oligarch Gregory Arkadin, as he attempts to cover up his past as a sex trafficker in Poland. He convinces American smuggler Guy Van Stratten that he suffers from amnesia and needs help piecing his life together. As Strattan travels Europe on his mission, he uncovers the terrible truth and learns that the billionaire is having everyone he's spoken to killed. When filming was complete, "Mr. Arkadin" went through a series of re-edits, resulting in multiple versions, all of which Welles was unhappy with, and one of which had removed the flashback element altogether.

Jonathan Rosenbaum, who edited the 1992 book "This Is Orson Welles" — a compilation of conversations between Welles and fellow writer/director Peter Bogdanovich — wrote an essay entitled "The Seven Arkadins," in which he breaks down the seven versions of the film. Criterion maintains there are "at least eight 'Mr. Arkadins': three radio plays, a novel, several long-lost cuts, and the controversial European release known as 'Confidential Report.'" There does seem to be some confusion over how many cuts of this movie there actually are, but Welles was certain that none of them measured up.

Orson Welles couldn't even think about Mr. Arkadin

In "This Is Orson Welles," Peter Bogdanovich and Orson Welles discuss "Mr. Arkadin" — something Welles was reluctant to do with the American press, owing to his experiences with having the film taken away from him during the editing process. During the conversation, Bogdanovich mentions that the version of the film, "that's in general release" (There were multiple general release versions across different countries) did not feature the flashbacks, prompting Welles to remark that he has a "block on the rest" of how the narrative was supposed to be told. The director went on to say:

"I just hate to even think of it. It was the best popular story I ever thought up for a movie, and really it should have been a roaring success. I'd love to make that story again [...] it's a super movie story. It was blown, blown, blown by the cutting."

Aside from the removal of the flashback sequences, Welles reveals there were two major scenes that never made any of the final cuts and which showed Arkadin, "as a sentimental, rather maudlin Russian drunk." He previously spoke about his dismay following the editing debacle on "Mr. Arkadin" in an interview with French film magazine Cahiers du Cinema, in which he referred to the movie as, "the real disaster of my life," and a "flawed masterpiece." Which considering his consistent issues with studios over editing and artistic control, and the multiple unfinished Welles films across his career, is saying something.

'It's as if they'd kidnapped my child'

In a career in which Orson Welles infamously clashed with studios, "Mr. Arkadin," at least in Welles' estimation, stands as his worst experience making a film. As he told French magazine L'Avant-scène Du Cinema:

"I thought it could have made a very popular film, a commercial film that everyone would have liked. In place of that ... I'm afraid to see it! [...] The film was snatched from my hands more brutally than one has ever snatched a film from anyone ... it's as if they'd kidnapped my child! They brought in another cutter who pretended to have 'saved' the film."

Of all Orson Welles' films, "Mr. Arkadin" is far from the worst. Christopher Nolan cited it as one of his top 10 films in the Criterion Collection, highlighting the "heartbreaking glimpses of the great man's genius" that remain between the edits. Elsewhere the New Yorker referred to the film as "extraordinary" and "unjustly unrecognized."

That hardly holds for Welles as a director. Despite dying a Hollywood outcast He is perhaps the most celebrated filmmaker in the history of cinema, which just goes to show that his assertion that, "The people who have done well in the system are the people [...] who want to make the kind of movie which producers want to produce," isn't necessarily true. After a career spent battling to realize his own unique visions and fighting against studio interference, Welles has done not just well but arguably better than any other director. Which is probably why he was so frustrated that "Mr. Arkadin" was wrestled away from him before he had a chance to finish his version and give audiences the chance to evaluate the film as he intended it.