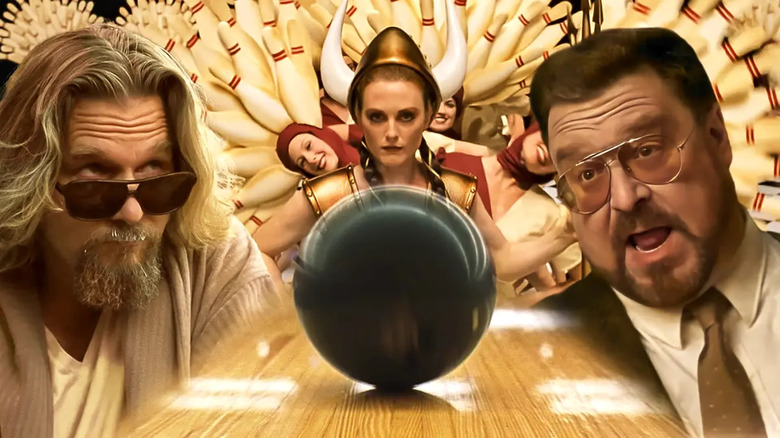

How The Big Lebowski Went From Box Office Bomb To Bonafide Cult Classic

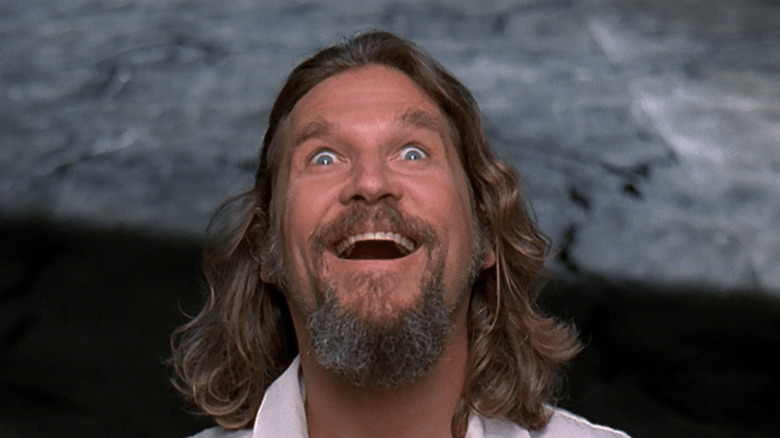

The story goes that Belgian bartender Gustave Tops invented the Black Russian cocktail back in 1949 to honor the U.S. Ambassador to Luxembourg, who was visiting Brussels at the time. Sources vary, but it is estimated that sometime in the '50s or early '60s Tops, or some other mixologist, later added cream to the blend and gave birth to the White Russian. The drink never made the A-grade of cocktails and might have died out altogether if it hadn't found its moment in the spotlight as the preferred tipple of Jeff "The Dude" Lebowski (Jeff Bridges) in "The Big Lebowski."

Nowadays the White Russian is synonymous with the film and you can get it in just about any cocktail bar. Has anyone ever ordered one without seeing the movie first? Only a handful of movie characters are so well-known for their choice of alcoholic beverage. Of course, there's James Bond and the Vesper Martini, and I can't order a Heineken without hearing Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) from "Blue Velvet" yelling: "F*** that s***! Pabst Blue Ribbon!" But that is a sign of how much of a cult favorite "The Big Lebowski" has become; it even has its own cult cocktail.

Like many cult movies, "The Big Lebowski" initially made an inauspicious debut with critics and audiences. Reviews were mixed and it performed poorly in the States, taking just $17 million against a budget of $15 million before creeping to $46 million internationally. By contrast, its critically adored predecessor, "Fargo," took $25 million at home on a $7 million budget on its way to over $60 million worldwide. You'd think everyone would have been falling over themselves to see the next Coen Brothers joint after that success; so why did "The Big Lebowski" underwhelm at first, and how did it become such a cult classic?

The Big Lebowski had a tough act to follow

After making its debut at Sundance Film Festival in January 1998, "The Big Lebowski" ambled out of the gate to meet the general public on March 6th. It surely suffered from proximity to "Titanic," which was still leaving everything in its wake at the box office, racking up over $95 million in that March alone when it also swept the Academy Awards with 11 Oscar wins. There are signs that "The Big Lebowski" would have struggled even without James Cameron's blockbuster: It opened against "U.S. Marshals," which took almost as much money in its opening weekend as the Coens' film managed in its entire domestic run.

More damagingly, expectations were set incredibly high for the Coen Brothers' next film after "Fargo." In the early stages of their career, the Coen Brothers were often dismissed as talented filmmakers who favored style over substance, but their dark kidnapping comedy changed all that, largely thanks to their first fully three-dimensional character to date, Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand). The heavily pregnant police chief gave the film a warm humanistic center lacking from their previous movies. It was a sign that the Coens were maturing as artists, and critics and audiences ate it up. "Fargo" was nominated for seven Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director, and McDormand deservedly picked up the Best Actress award for her performance. Previously, only "Barton Fink" had received any Oscar nominations at all, and "Fargo" was taken as a sign that the Coens were becoming accepted by the mainstream.

"Fargo" was a tough act to follow and perhaps everyone expected more of the same, maybe even another step into Oscar-worthy respectability. Whatever audiences were hoping for, it clearly wasn't "The Big Lebowski."

A movie that needs time to settle

After almost 40 years of the Coen Brothers, we now delight in their ability to constantly wrong-foot us, hopping from genre to genre and taking risks with their narratives; just take their Oscar-winning triumph "No Country For Old Men," where the protagonist is murdered off-screen. In 1998, however, "The Big Lebowski" might have seemed like a return to their old tricks after the relatively low-key "Fargo," and perhaps audiences didn't feel like they needed another kidnap caper.

Even at the time, anyone paying attention to the Coen Brothers' filmography shouldn't have been so surprised by their latest left turn. After all, they had followed their pitch-black debut "Blood Simple" with the zany "Raising Arizona," and the confounding "Barton Fink" with the screwball homage "The Hudsucker Proxy."

Whatever the case, perhaps the biggest cause of "The Big Lebowski's" initial failure is that it's a movie that requires multiple viewings to fully appreciate. That is often the case with cult movies, which often take years or even decades to find their true audience. A good example is "Withnail and I," which also made little impact at the box office when it was released in 1987 before being adopted by impoverished British students who saw something of themselves in the cash-strapped, drunken protagonists.

As for "The Big Lebowski," I didn't like it all that much when I first saw it. I felt it was inferior to "Miller's Crossing," "Barton Fink," and even "The Hudsucker Proxy" (yes, I'm one of that movie's few ardent fans). It didn't grab me after a second viewing, either, but there was still something about it that kept me coming back. The third time around, I was hooked.

What makes The Big Lebowski such a cult favorite?

What exactly is a cult movie? It's very subjective, but there are several categories that "The Big Lebowski" covers with addled aplomb. You have flicks so offbeat and diverse that they automatically alienate the squares. In that pot, there are films like "The Rocky Horror Picture Show" with its love-obsessed aliens and "Pink Flamingos," which puts us on Team Babs Johnson (Divine) as she strives to become the filthiest person alive.

Then you have stoner classics like "Up in Smoke" which overlap with hangout movies like "Dazed and Confused," films that derive their pleasure from just spending a few hours in the company of the characters. There are also movies with a high quotability factor, like "This is Spinal Tap" or "Withnail and I," because cult aficionados love quoting dialogue at each other. Broadly speaking, cult movies are outliers that make you feel like you're part of a special club because you love something that many mainstream viewers overlook or reject altogether.

"The Big Lebowski" falls into all these categories. It is an outsider movie through and through, putting an unemployed stoner protagonist in the traditional private eye role. The Dude bumps up against all sorts of oddballs and lowlifes but the main villain is the "Big" Lebowski (David Huddleston), the one member of the "respectable" society he encounters. His penchant for a spliff also puts it in the stoner category and the meandering plot makes it a strong hangout film, too.

Line for line, "The Big Lebowski" may also be the most quotable movie of all time. Even after about 40 viewings, I'm still picking out plenty of gems. In short, it may not be an extreme example of a cult classic, but it is perhaps the most cult movie for your buck.

The Big Lebowski's resurgence as a cult classic

"The Big Lebowski" was recognized quickly for its cult potential. Steve Palopoli of Metro Active wrote about it as early as 2002, discussing it as a modern-day savior of the cult movie. That same year, the first Lebowski Fest took place in Louisville, Kentucky. The event is still going strong today, a place for fans, aka "Achievers," to "drink White Russians, throw some rocks, and party with an array of Dudes, Walters, and Maudes (not to mention a nihilist or two)."

In 2005, "Lebowski" fandom took on a spiritual dimension when Oliver Benjamin, "The Dudely Lama," founded his own religion based on the film. Dudeism, or The Church of the Latter-Day Dude, interweaves quotes from the movie with the ancient wisdom of the Tao and Buddhism, creating a surprisingly coherent philosophy that has gained many followers who see it as a release from the pressures of high-intensity modern life. At the last count, there are over 600,000 ordained Dudeist Ministers around the globe and, in the United States at least, you can legally have one oversee your wedding.

Cinema is littered with movies that miss their audience the first time around, develop a cult following, and later receive critical reappraisal, sometimes from the critics who slated the film in the first place. John Carpenter's "The Thing" and "Withnail and I" are two such examples, and "The Big Lebowski" is a third. It was inducted into the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 2014 and now regularly ranks high in lists of the greatest comedies ever made. At this rate of progress, it wouldn't surprise me if it shambled into the lower reaches of the Sight and Sound Top 250 come 2032. But you know, that's just, like, my opinion, man.