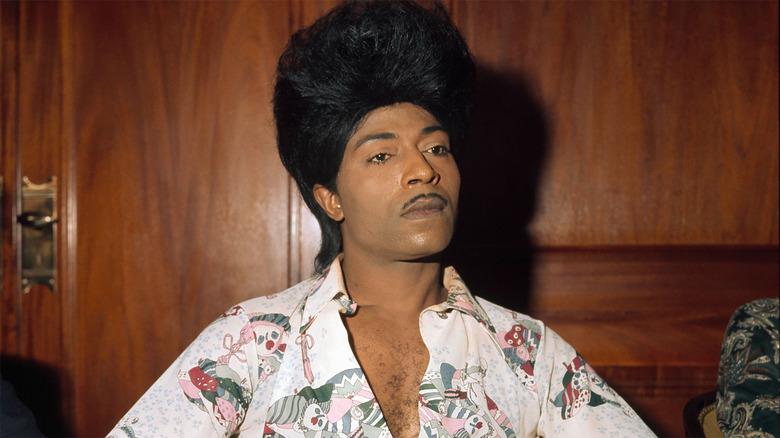

Little Richard: I Am Everything Review: Rock Doc Is An Uneven Tribute To A Troubled Artist [Sundance]

Lisa Cortés' music documentary "Little Richard: I Am Everything" is described on the Sundance website as an "eye-opening" look at the "Black, queer origins of rock 'n' roll." This is partially true: I learned a lot about the early life of Richard Wayne Penniman — known by his stage name Little Richard — that I did not know before, and much of it was very interesting. Often dubbed the "architect of rock and roll," the musician, songwriter, and occasion minister led a fascinating life that oscillated between extremes. He comes across as an exceptionally talented and passionate man with deep, inner turmoil.

I only wish the documentary spent more time celebrating his music.

In some ways, it's easier to study a pop culture icons like Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, or Kurt Cobain — they have clear arcs in the industry and tragic ends, giving a clear, definitive ending to their story. Then there are figures like Johnny Cash and Aretha Franklin, who despite having a clear "breakout" period early in their career, stayed active in the industry, reinventing themselves along the way. The problem with Little Richard as a pop culture figure is that he has a very messy legacy, and Cortés really struggles with balancing her celebratory intentions and needing to be transparent about what actually happened.

There are multiple layers in "Little Richard: I Am Everything": there's the queer subcultures that Richard Wayne Penniman borrowed from and popularized to create a new sound — one that would act as a blueprint for later rock artists; there's his breakthrough success in the '50s and his later career making gospel music but touring on his old hits; and, there's Penniman's own inner conflict over his religion and his sexuality, which sometimes manifested as public, homophobic and transphobic statements. It's really hard to reconcile this — yes, he was an inspiration to queer director John Waters, but he also said in a 2017 interview that "God, Jesus, he made men, men, he made women, women ... you've got to live the way God wants you to live." Ultimately, Cortés made a movie promoting a queer artist who, in his last televised interview, doubled down on his decision to choose "faith" over "fame." Would he have even wanted this film?

Slippin' and a slidin' (with the truth)

Cortés has a lot of ground to cover with her documentary, and she introduces some really interesting perspectives right from the start. We get a good sense of Penniman's childhood, and how both poverty and religious ideology really informed his outlook on life. The reveal that Penniman was involved in the local drag scene, for example, was really intriguing, as was the explanations by ethnomusicologists and other similar experts on the queer history of Georgia. It was unexpected, but very cool, to see names like Ma Rainey and Sister Rosetta Tharpe come up. I also enjoyed hearing stories from previous bandmates, family, and friends — these provide a glimpse of who Little Richard really was.

However, Cortés makes two odd choices here that hurt the documentary overall. First, she rushes past Little Richard's pop cultural dominance to focus on his role as the "architect." Sure, we're shown the ways he lived the rock star lifestyle, but we don't get a lot of details about his really big hits. After the audience learns about the origin of "Tutti Frutti," and experts explain why the playing style was so innovative, we're told the music tapped into teenage sexuality, and we get a lot of theoretical content. What we don't get is actual history and anecdotes. I wanted more information about Little Richard's life and career in that period between 1956 and 1958, before he quit the industry to become a born again Christian.

The other questionable creative decision in "Little Richard: I Am Everything" is the use of artistic "recreation" scenes. Essentially, there are a few moments when someone is describing Penniman performing, and the documentary shows a Black musician essentially playing the role of Little Richard in highly stylized empty performances spaces. There are shots of dust and a twinkle of notes hinting at some whimsical magic at play. Tonally, it's very jarring and more than a little cheesy.

I love the idea of having contemporary Black artists perform pivotal moments of Little Richard's life in theory, but it's not executed well here. I wish at some point in the production, someone had noticed that Cortés was creating a beautiful, fascinating tribute to the Black, queer roots of rock and roll, and said hey — let's just do that. I think the cover sessions would have worked better in that context, especially if there were more of them featured throughout (minus the magic dust).

Who was Little Richard?

Cortés is trying too hard to exaggerate Little Richard's lasting cultural significance and present him as a victim of circumstance, and that wasn't necessary. There's a real "us vesus them" energy in the documentary that doesn't reflect well on its central artist, and doesn't always ring true. For example, it's brought up more than once that he had never won a grammy when he presented at the 1988 Grammy Awards. This sounds bad; however, the Grammy Awards didn't begin until 1959, and his big hits ("Tutti Frutti," "Long Tall Sally," "Slippin' and Slidin'," etc.) all came out before then. Plus, in the early days, the Grammy Awards tended to recognize crooners like Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland, and Henry Mancini. (And he did get the Lifetime Achievement Award in 1993).

I'm going to say something potentially provocative here, but bear with me. Little Richard draws natural comparisons to pioneers like Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Chuck Berry, and a major argument Cortés presents over and over again is that the "Tutti Frutti" laid the groundwork for rock and roll, yet unlike other (white) artists, Little Richard never got his due. The implication is that he was robbed by the industry, and if it wasn't for racism and homophobia, he would have enjoyed much more fame, recognition, and wealth.

I don't think it's that simple.

Yes, Little Richard was massively influential, and his music changed the world. Yet, he quit the industry a short time into his fame, and when he returned, he was not able to reinvent himself for the next generation — other than as a nostalgia artist. This is common: Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis also had career lulls after their breakthrough success (but for them, scandals really hurt their public image and celebrity). Heck, people forget that Elvis was kind of a joke in the '60s until his '68 comeback special (and he was so spectacularly talented — "If I Can Dream" gives me chills every time). I'm sure Little Richard being pulled between his religious faith and over-the-top flamboyant personality really hurt him commercially in terms of releasing a hit record. The back and forth in particular was likely detrimental, especially because he'd be appealing to polar opposite demographics. And I'm sure racism and homophobia contributed to his problems. The issue is that the documentary doesn't know how to handle all of this history, so the resulting portrait is rough, unfinished, and unconvincing.

I think Cortés did not succeed in making Little Richard likable, nor did she portray him honestly — which I assume was the intention behind making "Little Richard: I Am Everything." This is a complicated subject with a lot to cover, and that's very difficult to do in a feature-film length. In the end, I don't think audiences will come away with a better appreciation for his work, but at least it's starting the conversation about the "Black, queer origins of rock 'n' roll" — a subject that really needs further examination.

/Film Review: 6 out of 10