Bela Lugosi's Follow-Up To Dracula Featured A Scene Too Disturbing To Keep In The Film

Of the many macabre quotes attributed to writer-poet and goth luminary Edgar Allan Poe, one of the most implemented in fiction is his insistence that the death of a gorgeous woman is the "most poetical topic in the world." It's the focal point of his celebrated 1841 short story, "The Murders of the Rue Morgue," concerning the procedural investigation into the brutal death of a mother and adult daughter. It's a detective story crafted before such a term existed, and one of its big-screen adaptations featured a completed scene so vicious that the powers-that-be kept it from seeing the light of day, no matter how "poetical."

The year is 1932. Audiences are reeling in the wake of two major horror game-changers; James Whale's "Frankenstein" and Tod Browning's "Dracula" were both fairly faithful adaptations of their respective novels the previous year and (no thanks to the restrictive Hays Code) pushed the boundaries of what moviegoers could handle. Alongside Browning's "Freaks," Robert Florey's "Murders in the Rue Morgue" would do the same.

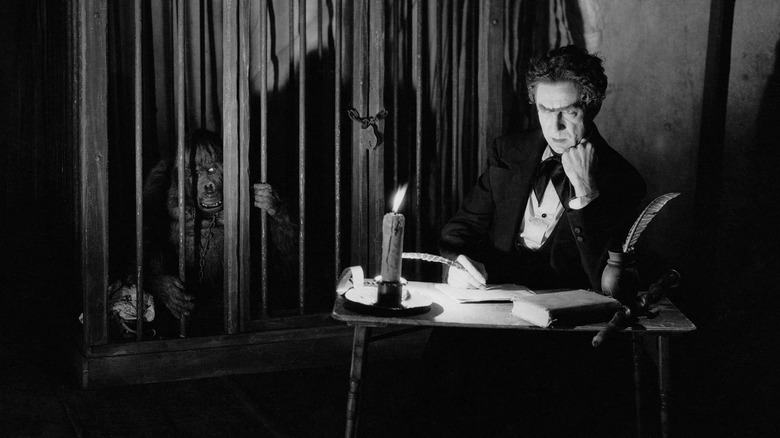

This adaptation would play fast and loose with its source material, transforming it into a vehicle for rising genre icon Bela Lugosi. Therein, sideshow performer Dr. Mirakle (Lugosi), kidnaps women from the streets of Paris with the aim of mixing their blood with that of his gorilla Erik in an evolutionary crusade. The chosen women were to be brides of science, canon fodder for the advancement of humanity, the doctor reasoned. One such victim, played by a pre-"What's My Line?" Arlene Francis, undergoes such onscreen torment that her torture scene, which was originally supposed to open the film, was eliminated by the censor board.

The Hays Code strikes again

The scene is a mere YouTube search away these days, despite the efforts of the Golden Age-era censoring bodies.

It begins with Lugosi finding Francis cowering from a violent fight she witnesses by the Seine; Francis has no name beyond her credit as "Streetwalker," so it's clear how things are going to go for her. The doctor whisks her away to his lab, where the notorious scene unfolds: bound to crossed beams and standing in torn underwear, the woman screams as Mirakle, aproned like the sadists of "Hostel," takes a nonconsensual blood sample. "We shall know," he proclaims, "if you are to be the Bride of Science!" He then deems her blood "rotten," tainted by a life of sin. As she succumbs to her wounds, he drops to his knees before her body and wrings his hands together as if in prayer. It's a foul religious image, as perverse and sublime as that of Shelley Winters' pre-death prayers in "The Night of the Hunter."

David J. Skal's cultural history tome "The Monster Show" chronicles the pearl-clutching reactions to the scene, the most damaging of which came from those who had the power to stamp it out of the film entirely, like the New York State Censor Board. Skal writes of the board's judgments:

'Reel 2 — eliminate all distinct views (5) of the girl bound and tied to cross beams... all views of her writhing in agony — all views of Doctor standing over her, holding her arm while he tortures her. Eliminate all sounds of girl and loud cries and moans of agony and fear, and accompanying dialogue..."

Ultimately, Arlene Francis' role in the film was decimated, even cut from Universal's 1936 rerelease four years later. So much for poetry.