Production Designer Anton Furst Took The Same Creative Approach In Making The Sets For Batman And Full Metal Jacket

Since 1989, we've had eight live-action "Batman" movies (not counting the DCEU films) and have yet to see as good an on-screen representation of Gotham as the city from Tim Burton's first movie about the Caped Crusader. At least, that would be true if it wasn't for Bo Welch's elegant expressionist nightmare from "Batman Returns." Still, "Batman" production designer Anton Furst created an indelible version of the Dark Knight's home turf that holds up to this day.

As the designer told TIME magazine in a 2001 interview, his "riot of architectural styles," erected at England's Pinewood Studios, led director Tim Burton to refer to his Gotham as a city where "hell erupted through the pavement and kept on going." So effective was this foreboding, oppressive, New York-gone-wrong aesthetic that Furst nabbed the Oscar for Best Art Direction in 1990. It was a well-deserved win for the British artist, who had previously worked on Stanley Kubrick's "Full Metal Jacket," for which he designed a similar yet distinct hellscape by recreating Vietnam in North London.

In fact, Kubrick's celebrated 1987 war movie was completely shot in and around the English capital, allowing the famously reclusive director to retreat to his nearby country home with ease. Kubrick had apparently been impressed by Furst's work on 1984's "The Company of Wolves," for which he'd created a shadowy dreamworld that apparently prompted the director to say: "Get a hold of that guy, he's our designer." And although, in many ways, Kubrick and Burton's movies couldn't seem more different, it seems their production designer took a similar approach to his work on both.

Bringing Vietnam to London

Once Kubrick decided on London as a shooting location for his Vietnam War movie, he faced a challenge; how do you make England look like Indochina? The answer came in the form of Furst and several locations around the city — the most important being Beckton Gas Works in the borough of Newham. The derelict site mostly doubled as the bombed-out city of Huế, though some parts were used as streets in Da Nang, according to Matthew Modine's "Full Metal Jacket Diary." The real central Vietnam city had been hit hard during the Tet Offensive and Kubrick, using thousands of still photos of the actual location, set out to create his version of the city.

According to John Baxter's biography of Kubrick, this involved a week of destroying and "half destroying" some of the site's buildings using "explosives and earth-moving machinery." Then, Furst directed a crew armed with "sledgehammers and a wrecking ball" to pummel and beat the remaining structures, giving them a war-torn aesthetic. Palm trees from Spain completed the look, alongside a "team with hammers and a modified flame-thrower" who "'distressed' any walls which might appear in the action, and seared the ground, sometimes accidentally setting the actors' boots or trousers on fire."

The result was a pretty convincing Huế, especially considering it was actually the Thames marshes. But as Furst acknowledged, precise accuracy wasn't the guiding principle for him and Kubrick. In fact, the designer said he was aiming for "the image of hell" rather than "complete historical accuracy" with his version of "the burned out city of Quai." Two years after filming wrapped on "Full Metal Jacket," Furst would once again bring the image of hell to the UK when "Batman" began filming at Pinewood Studios in the winter of '88.

Evocation over recreation

When Burton came to shoot his $35 million blockbuster, he chose Pinewood partly as a way to get away from the chatter of Hollywood, where his casting of Michael Keaton had prompted a wave of fanboy outcry. But its giant backlot also allowed the director and Furst to construct their 600-foot-high Gotham set, where they would shoot six days a week, typically until 5:00 or 6:00 a.m. It was a fairly grueling shoot, according to everyone involved, with cast and crew often not seeing daylight for weeks on end.

Compounding what must have been the surrealness of the experience was Furst's all-encompassing, oppressive, industrial cityscape, which he said was made up of "all the elements of Manhattan exaggerated" and was designed as if a town had been "run by a criminal organization for a long time."

This was a different type of degradation than that of "Full Metal Jacket" and its Beckton Gas Works set, which sounds like it was literally as dangerous as it was supposed to look. Both Burton's Gotham and Kubrick's Huế were hellish, but the former was a kind of love letter to urban decay while the latter evoked a historical reality. What united the two was the "broad stroke" that Furst used when conceptualizing them both. His technique of eschewing "complete accuracy" in favor of a more expressive interpretation of the subject matter allowed him to convey a kind of evocative cinematic reality that went beyond mere recreation. As the production designer himself said, "I work on metaphors and parables of situations without trying to recreate it too closely."

Realer than real

Furst passed away in 1991, leaving behind an enviable legacy as a production designer. What really stands out, especially in the case of "Batman," is his ability to express darker themes through production design. The film's 2nd Unit Director, Peter MacDonald, remembered him as "an incredible, dark, interesting character" that "could have played a part in 'Batman' very easily."

Even in "The Company of Wolves," the film that had brought Furst to Kubrick's attention, that dark sensibility was on display. Which made him a good fit for "Full Metal Jacket," a film that flirted with dark humor and dealt with some pretty harrowing subject matter. But it made Furst an even better fit for "Batman," as evidenced by his Oscar win and the way his Gotham endures as one of the best on-screen interpretations of the fictional metropolis yet.

Furst was clearly at his best when not shackled to reality. With Kubrick's movie, he was beholden to a real-life event that had become part of the cultural consciousness. But with Gotham, Furst could use the fictional concept as a jumping-off point to paint his own vision. And he clearly flourished in that environment.

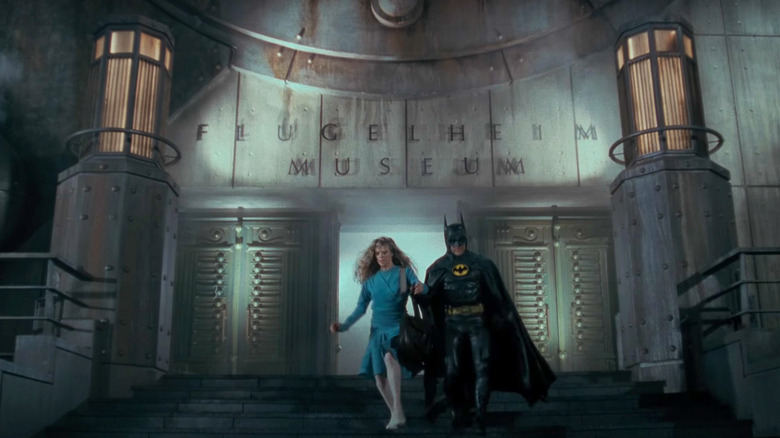

I was completely enraptured by the look of "Batman" as a kid, to the extent that its rusted girders, gothic archways, steam-laden alleys, and degraded storefronts feel like the architecture of my own mind in some weird way. I can recall all those small details, like the giant vents of the Flugelheim museum, in crystal clear detail. Other than Bo Welch's Gotham in "Batman Returns," I can't think of another film that has felt like that. All of which is to say that Furst's way of working within the sphere of "metaphor" and "parable" can often yield results that feel more real than reality itself.