Clint Eastwood Borrowed A Small-But-Impactful Element Of Psycho For Play Misty For Me

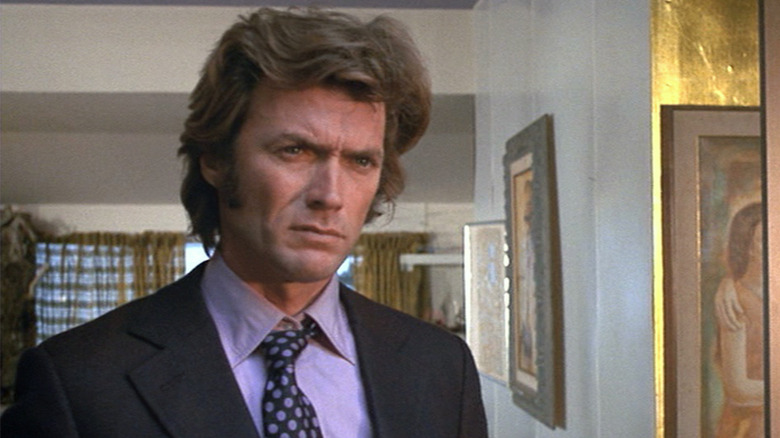

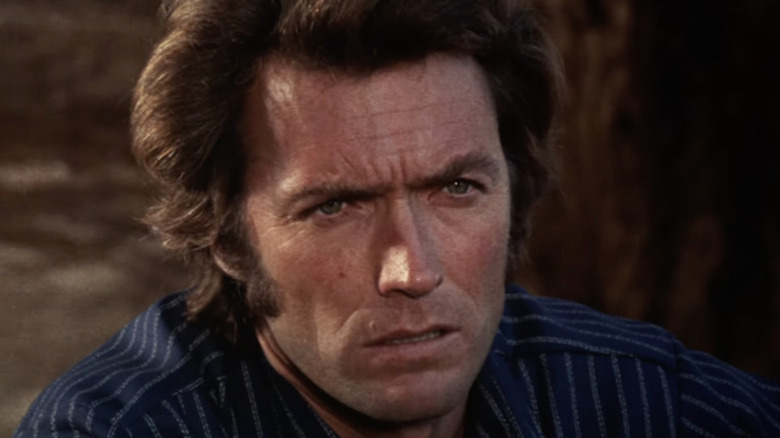

Clint Eastwood had himself quite the contradictory 1971. He starred as a wounded soldier victimized by a seminary headmistress and her young charges in the Civil War gothic "The Beguiled," directed himself as a DJ victimized by an obsessed ex-lover in "Play Misty for Me," and victimized perps and suspects with quippy aplomb as a Miranda-rights-flouting cop in "Dirty Harry." It's the most pivotal year in the star's career, the moment he proved he was willing to tweak his macho image by playing rakish, manipulative men who have their casual cruelty revisited on them tenfold. There's a guilty conscience that roils just beneath the surface of Eastwood's best work, which is probably why he remains a particular favorite of male critics. We're drawn to his characters' above-it-all curtness but empathize, quite uncomfortably, with their emotional transgressions.

These qualities needn't be a referendum on Eastwood the man, and, if you've ever read an interview with the star, you know full well that he's uncomfortable drawing parallels between his art and his personal life. Is it deflection or genuine aloofness? Does it matter? An excellent example of this reticence can be found in a 1971 interview Eastwood gave to Stuart M. Kaminsky, where he compares his psychological thriller to the audience-goosing mechanics of Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho."

The perils of sleeping with Norman Bates

In discussing Jo Heims' story for "Play Misty for Me," Clint Eastwood reveals that he was drawn to the material because "there are incidents like this in everyone's life, to some degree, this whole thing of interpretation of commitment, or misinterpretation of commitment." Eastwood's film hinges on a decidedly extreme misinterpretation that compels a mentally fragile woman (the great Jessica Walter) to mistake a one-night stand for a firm romantic commitment. He rebuffs her gently at first, but she's determined to have him for herself. When she slashes her wrists in his home and assaults his housekeeper, she's institutionalized. This is just the beginning of his nightmare.

Eastwood tells Stuart M. Kaminsky that everyone, regardless of gender, can surely identify with a situation where a sexual partner tries to force a romantic bond. But Walters is playing a psychopath, which creates not just distance with the audience, but a complete disconnect. How did Eastwood deal with that? As he explained to Kaminsky:

"A lot of times, with stories about psychotic people, there's no identification factor. In a picture like 'Psycho,' the real highlights of the film are strictly the shock and the suspense. It was of course fabulous to have that scene where she sees the skeleton in the basement, but then they almost destroyed everything later with all that unnecessary exposition."

The brutal end of an ill-advised affair

Clint Eastwood learned the value of heightened suspense from Hitchcock. "Those attacks could be sprung upon the audience with the same kind of suspense and energy as Hitchcock used, I thought, but other than that, I saw it as a story of constriction," he told Stuart M. Kaminsky. It is a story of constriction, one that's built around a minor Bay Area celebrity on the verge of breaking out of regional fame to the big time. Does this sound like a certain movie star circa 1971?

"Play Misty for Me" ends with Eastwood punching Jessica Walters' character through a window and onto a rocky outcropping adjacent to the Pacific Ocean. The audience feels a palpable sense of relief. He's finally free of this nut who couldn't take no for an answer. There's better for him on the horizon (Donna Mills, to be exact). There's an incorrigible romantic in Eastwood (see "The Bridges of Madison County"), but there's also, judging from the movies, a get-off-my-lawn crank who wants every broken relationship in his life to end on his own terms — When I'm out, you're out, and if you can't accept that, I'll blast your clingy ass into the deep blue briny. It's ugly, but if you've ever watched "Play Misty for Me" or its spiritual sibling, "Fatal Attraction" with an audience, you know that this feeling is primal.

Eastwood isn't asking you to like his character. He may even hate him, himself. It doesn't matter. What you do with it is on you.