Kiyoshi Kurosawa Wanted Cure To Feel Like An American Detective Story

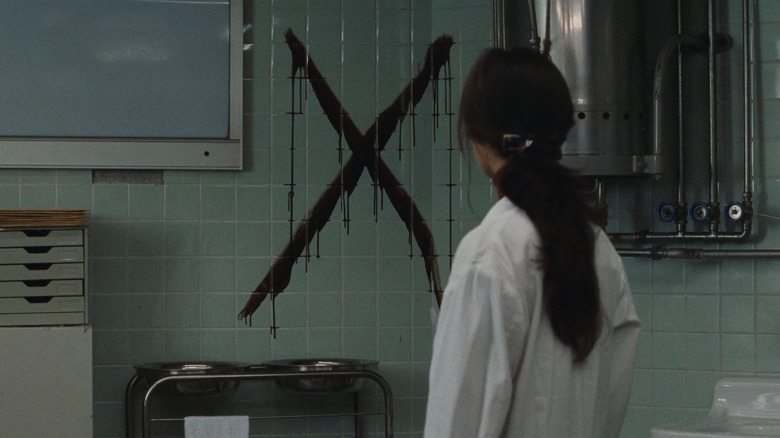

"Cure" is a murder mystery whose culprits cannot remember why they chose to kill to begin with. It is a serial killer narrative whose mastermind may be nothing more than a vessel for the desires of others. The detective that hunts him is dedicated but untrustworthy. The film's editing deteriorates along with his psyche. His wife reads a copy of "Bluebeard," the famous French folk tale of a man who murdered his many wives. By the end of the film, the detective has killed her, compelled either by the hypnotic suggestion of a mysterious phonograph or by his own sublimated frustration. The most horrific aspect of "Cure" is that there may be no difference. All it takes to transform a law-abiding citizen into an unthinking killer is running water, the flicker of a lighter and a black X.

Critics have spent the past several years trying to figure out what director Kiyoshi Kurosawa meant to say in the film. In an AV Club review from 2002, Scott Tobias linked "Cure" to the infamous Aum Shinrikyo sarin gas attacks. (If you'd like to learn more about the attacks, I recommend Haruki Murakami's "Underground.") Adam Nayman says in a piece for Gawker that "Kurosawa is the great modern filmmaker of contagion, be it chemical, biological, or intellectual." Jeremy Carr, in his write-up for MUBI on the career of Kurosawa, claims the film "examines an individual's capacity for change in accordance with the world changing around them." Carr's writing comes the closest to Kurosawa's own words in a 2001 interview with IGN, where he compared the film to an American detective story.

'All the things that used to be inside of me...'

"'Cure' is indeed a psycho thriller and a detective story and I borrowed these genre styles from the American conventions," Kurosawa says. But "Cure" was to be a detective story with a difference. In Kurosawa's opinion, American detective stories are flat: "The protagonist, the detective, does not change throughout the film." A dogged detective who changes the world by solving a case, but does not change himself, did not interest him. Instead, the detective of "Cure" is transformed by his experiences. Takabe begins the film as a man who professes responsibility to his wife and his job. By the end, says Kurosawa, "he finds complete freedom by cutting himself off from [...] society."

"Cure" deviates from traditional detective stories in other ways, such as the question of motive. Whether the killers are brainwashed by Mamiya, or if Mamiya simply encouraged them to act on their desires, is left ambiguous. The killers themselves are left in a vegetative state, unable to recall why they committed the crime. As for Mamiya, he could be a conniving nihilist that has orchestrated everything behind the scenes. But he could also be a hollow shell blindly acting on impulse.

We know from the IGN interview that Kurosawa cares about motive; according to him, he makes movies by asking himself the question, "What would a certain character or individual person do in a certain situation?" Yet he rebuffs the interviewer's efforts to link the themes of "Cure" to his time studying sociology in university. Once he started making films, he says, he "stopped thinking about sociology altogether."

'...Now they are all outside'

Another way in which "Cure" differs from its brethren is its reluctance to use close-ups. "It is my opinion that directors these days use way too many close-ups of human faces," Kurosawa says. This sounds bizarre, initially. The murderer confessing guilt, the noir hero crumbling under the strain and the witness shaking with fear are all classic scenes in detective stories that are heightened via the use of close-ups. Yet once again, Kurosawa was aiming for something more than just a classic detective story.

"What I want to accomplish with my films," he says, "is to leave it [to the audience] to come up with the answers." The staging in "Cure," especially the murder sequences, is one of the most memorable aspects because it leaves so much to the imagination. As Nayman says, "evoking anxiety via blocking and body language" is Kurosawa's secret weapon. The actions of the characters remain mysterious even when the logistics of killing are clear as day.

As far as Kurosawa is concerned, "Cure" is a movie made from his experiences watching other movies. "I watched so many films," he says, "and those are the elements I learned from the films I had seen." Certainly, "Cure" is not wholly revolutionary. David Fincher's "Se7en" had terrified American audiences two years earlier in 1995. Like "Cure," "Se7en" was a frightening crime story about detectives stretched to the breaking point in pursuit of a killer. Its shocking murders and nihilistic ending had more in common with the horror genre than traditional mysteries. Similarly, as Adam Nayman points out, hypnotism has been a recurring obsession in film since at least 1920's "The Cabinet of Dr. Calgari." The weirder aspects of "Cure" merely borrow from a mystery tradition spanning decades.

X marks the spot

Even so, there's something distinctive about how "Cure" arranges these ideas. Compared to the bloody tableaus of "Se7en," the death scenes in "Cure" are presented matter-of-factly. Their horror stems from how effortlessly a seemingly ordinary person (such as a police officer or a doctor) might murder somebody else. As Takabe and the psychologist Sakuma investigate the case, the solution itself proves to be poison. Mamiya is hollowed out by his study of mesmerism, left to a slipstream existence. Sakuma is infected by whatever Mamiya knows, and kills himself. Takabe is seemingly liberated by what Mamiya teaches him, and yet his liberation transforms him into a monster. The closer the characters come to "the truth," the further they diverge from acceptable behavior.

"Cure" has attracted many followers. One of them is Bong Joon-ho, who listed the film on his 2022 Sight and Sound ballot. In 2003, he released "Memories of Murder," a film based on a then-unsolved murder case. "Memories of Murder" is funnier and more humane than "Cure," mining real tragedy from the failure of its flawed protagonists to catch the culprit. But its willingness to explore the uncertainty that haunts most real-life crime cases, as well as the way that ordinary people warp under societal pressure, is reminiscent of Kiyoshi Kurosawa's work.

David Fincher's "Zodiac" and even the HBO television series "True Detective" inhabit parallel circles of hell. Kurosawa may have created "Cure" by borrowing from his favorite movies. But these days, as many modern films could trace their birth to "Cure," that black sigil on the walls of Japanese cinema.