Why Technological Limitations Are Vital For Star Trek's Drama

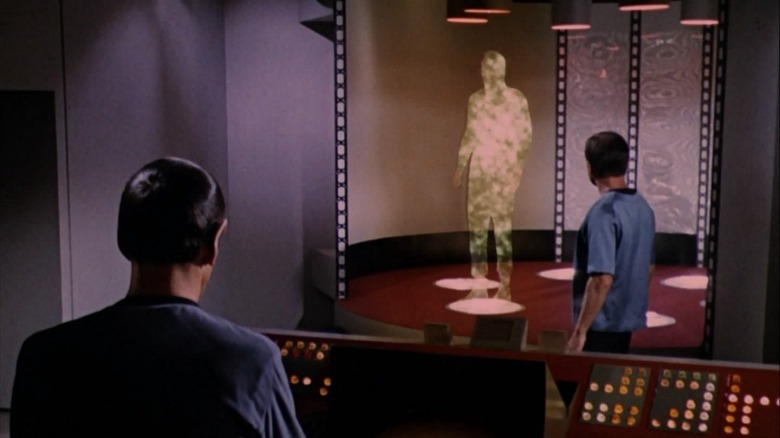

"Star Trek" is set in a utopian future that is, vitally, post-war and post-capitalist. By the show's timeline, humankind had to survive a "rough patch," rife with conflict and destruction — World War III and the Eugenics Wars are often referenced in dialogue — before it could emerge on the other side as a technological wonderland and pacifist utopia. The original series takes place from 2265 to 2269, and by then, humans will have mastered faster-than-light travel, food replicators, and miraculous transporters that can pulverize users into atoms and reconstruct them miles away on a planet's surface. All familiar diseases have been cured, and even hand weapons are explicitly nonlethal ("Set phasers to stun"). One might say a prime facet of "Star Trek" is that humans live in harmony with their inventions. Technology, "Star Trek" argues, will be our friend and our salvation.

Of course, "Star Trek" is hardly above the occasional "science run amok" plot, and it's all too common that a computer or a machine will accidentally be granted sentience, only to behave in ways that its inventors didn't expect. Just recently, the third-season finale of "Star Trek: Lower Decks" feature a trio of artificially intelligent drone starships that reprogrammed themselves and went on a spree of destruction.

But for the most part, technology is gentle and beneficial, and often, should a machine gain sentience, Starfleet officers approach them with sensitivity for their autonomy. When Geordi La Forge (LeVar Burton) accidentally creates a holographic Moriarity (Daniel Davis) on "Star Trek: The Next Generation," and the evil detective takes over the ship, Picard (Patrick Stewart) does not aim to kill him, but to negotiate. What does a newly sentient machine intelligence that thinks it's from 1893 want in the 24th century?

But there are limits

Given everything that characters can do in "Star Trek," however, there are still limits. All known diseases may be cured, but that doesn't stop new diseases from occasionally infecting the crew. As seen in the NextGen episode "Symbiosis," drug addiction is still rampant in parts of the galaxy. Ships may be able to travel 729 times the speed of light (the approximated velocity of Warp 9), but the writers of the show acknowledge that the Milky Way galaxy is 105,700 lightyears across, making quick jaunts to its outer reaches quite impossible. Food and clothing and small tools can be replicated out of thin air, but entire starships still need to be built and powered by more conventional means.

The "Star Trek" characters may live in a utopia of technology, but it will only ever bring them so far.

The limitations, however, are vital, largely for dramatic reasons. As author Phil Farrand once said in his unauthorized 1993 sourcebook "The Nitpicker's Guide for Next Generation Trekkers," if someone could create and entire fleet of starships with the push of a button, one wouldn't need to. If the Enterprise could handily destroy any ship it encountered with its weapons, possessed completely impenetrable shields, and could be 80 galaxies away in a matter of moments, what tensions could it encounter? It's vital that Starfleet vessels be more or less evenly matched with other aliens in "Star Trek," as it would force the characters to invent clever — and dramatically satisfying — solutions.

"Star Trek" has never been about power or dominance, but resourcefulness, ingenuity, and diplomacy. If a crisis arises, the Enterprise cannot instantly possess the tech to take care of it. Otherwise, well, where's the show?

Problem-solving skills

In the 1960s, the idea of a hand-held, wireless, flip-open communication device seemed futuristic. In 2022, the idea of a mere flip-phone is already moribund, having already been replaced by smart phones that are slowly becoming more and more like tricorders. In both cases — with communicators and with real-life phones — screenwriters have often felt the need to construct plot contrivances to remove such devices from their stories. In horror movies, to cite a broad example, a character may be seen checking their phone's reception and finding it to be null. This, of course, establishes that the character will not be able to phone for help when a woodsbound creature attacks. The tension is increased with the lack of telephone.

Ditto with "Star Trek." Good Trekkies will happily point out the number of times an "ion storm" or some other kind of fictional spatial interference prevents characters from being beamed back up to the ship, or from communicating with potential rescuers via comm badge. If the plot of a "Star Trek" episode requires characters to be isolated, then often its tech will need to be disabled to provide said isolation.

This not only provides satisfying drama, but is put in place to silence any nitpicking Trekkies who feel they might be able to out-clever the episode's scenario. "I would have just performed the Picard Maneuver, blasted a tractor beam at a meteor, and flung it at the Borg." Yes, yes. But the screenwriters already said power reserves were low. Let's not all pretend we're Stafleet captains, hm?

Tech limitations may be convenient screenwriting contrivances, of course, but such contrivances reveal just how necessary limits are when inventing "Star Trek" stories. Necessity vis-à-vis invention.

Trekking too far

Trekkies have internalized this necessity for technological limitations to such a degree, that we will often be the first to cry foul when Trek breaks its own rules. Which, regrettably, happens a lot.

To cite one of the most visible examples, the 2013 film "Star Trek Into Darkness," a film set in the alternate timeline of the Kelvin universe, offers what is more or less a cure for death. That film's villain, Khan (Benedict Cumberbatch) is a genetically altered super-solider from Earth's wartime past who enacts a complex revenge scheme. Late in the film, Captain Kirk (Chris Pine) dies of radiation exposure, and remains dead for a measurable period. Dr. McCoy (Karl Urban), however, is able to bring Kirk back to life using a poorly defined serum made of Khan's blood, collected earlier in the film. It sure seems like "Star Trek" now has access to a fluid very much like in Stuart Gordon's "Re-Animator." Does "Into Darkness" address what a sea change that would mean for the universe at large? It does not.

Perhaps most egregiously, the title ship from "Star Trek: Discovery" has discovered that the entire universe is populated by an endless network of microscopic interdimensional spores. In tying the ship's engines into this mycelial network, it can essentially teleport anywhere in the universe instantaneously. In other words, there is now no longer a need for trekking anywhere. Apologies, but that seems like a big f****** deal. Does "Star Trek: Discovery" ever address the widespread ramifications of its central technology? One that would fundamentally alter the very fabric of everything in "Star Trek?" It does not.

Trek is often quite consistent in its tech writing, and is always careful to remain inside a technology-based utopia.

But, well, not everything works perfectly.