The Mist And The Shawshank Redemption Are Two Very Different Films About The Importance Of Hope

Frank Darabont's adaptation of Stephen King's novella "The Shawshank Redemption" begins at the end of Andy Dufresne's life. The Portland, Maine banker has just been sentenced to prison for the rest of his days for murdering his wife and her lover and arrives at Shawshank State Penitentiary a fresh-faced shell of a man. One of the veteran inmates, Red (Morgan Freeman), believes he'll snap within 24 hours of his first day in stir, and bets on it. He loses that wager.

This is the beginning of an unlikely friendship, but it's not the last time Red will doubt Andy, largely because they possess divergent worldviews. Red, who's already served two decades at Shawshank, is resigned to a life in confinement. Oh sure, he sits for a parole hearing every so often and tells the board precisely what they want to hear, but the result is always the same. He's never getting out. There is no hope, and Red knows better than to entertain it.

For Andy, there is only hope. Without hope, he would swiftly make good on Red's initial read of his character. Andy finds hope in loftier things like music and risks solitary confinement or worse for blasting a selection from Mozart's "The Marriage of Figaro" from the warden's PA system. The prisoners in the yard are captivated by the ineffable beauty of the female voices. It's a brief, blessed moment. For a few minutes, Mozart's composition whisks the men off to some cherished place in their imaginations. Red is particularly mesmerized, but he worries that Andy is dabbling in the kind of false hope that "can drive a man insane." But for Andy, "Hope is a good thing, maybe the best of things, and no good thing ever dies."

The hopelessness of The Mist

Hope and decency and several good people die in Darabont's "The Mist." Made 12 years after "The Shawshank Redemption," this nihilistic adaptation of King's 1980 novella strands the audience in a pressure cooker of a grocery store where people are stocking up in the wake of a massive thunderstorm. When an ominously dense fog envelops their small Maine town, one that appears to mask an invading extraterrestrial force, the trapped customers project their own fears and hatreds onto the external threat and, eventually, each other. While our protagonist, David Drayton (Thomas Jane), cautions calm, Mrs. Carmody (Marcia Gay Harden), a deluded evangelical Christian, foments irrational discord. She crosses several lines of civility in frighteningly rapid succession, finally convincing a frightened, ignorant portion of the shoppers to consider human sacrifice.

In 2007, such madness was a worst-case scenario sparked by the Bush administration's eschewal of the "reality-based community." That scenario is now our reality. The U.S. is currently a splintered country where a major political party panders to and promotes wackos who believe, among other stupid things, their political opponents are pedophiles who harvest an adrenochrome narcotic from tortured children. While Mrs. Carmody might've been fringe in 2007, she has a kindred, kooky spirit in Georgia's Marjorie Taylor-Greene in 2022. In such a climate, where a grocery store like the one in "The Mist" could get shot up by a racist in clear, fog-less daylight, Darabont's film feels unnecessarily metaphorical. The monsters are here, and they are us.

As once-normal people take complete leave of their senses, those who've managed to keep their feet planted on "reality-based" terra firma might want to simply give up and escape. This is what David decides to do in the final moments of "The Mist," and, by god, does Darabont make him pay for it.

Two prisons, one twisted reality

For years, I've been fascinated by the degree to which "The Shawshank Redemption" and "The Mist" are in thematic conversation with each other (and, judging from this superb Blake I. Collier piece, I'm not the only one). In terms of outlook, they are products of their times. The former reflects the post-Cold War optimism of the Clinton administration, while the latter's cynicism is clearly vibing on the trauma of 9/11 and the subsequent military misadventures in Afghanistan and Iraq.

While I don't believe any movie is wholly apolitical, "The Shawshank Redemption," given its narrative that stretches from Harry Truman's presidency to Lyndon B. Johnson's with only a passing mention of John F. Kennedy's assassination, is notably devoid of political conflict. It's a movie, in part, about how cultural education sustains us. The music and the books in the prison library single-handedly upgraded by Andy via a dogged letter-writing campaign to the state legislature, improve the quality of incarcerated life for his fellow inmates. Art, in Andy's estimation, nourishes that thing that's "inside ... that they can't to, that they can't touch." That thing called hope.

The supermarket-bound war of "The Mist" is one of educated pragmatism versus anti-intellectual rage. People like David Drayton and Amanda Dunfrey (Laurie Holden) problem-solve because their lives depend on it, whereas Mrs. Carmody answers to a higher power than reason or fact. She operates as if she is in direct conversation with God, and this is where rational discourse dies. Her way is the highway to heaven. Anyone who doubts her is an agent of Satan and must be neutralized. America's political and media landscape is now rife with Carmodys, and they'd be laughable if they were so heavily armed.

The horrible toll of surrender

Frank Darabont told me in 2008 that "The Mist" was an "outraged liberal tract." I agreed then and still do, but, more than ever, it feels like his outrage is directed at his fellow ideological travelers. He made this film at a time when left-leaning celebrities were pledging to flee the United States if Republicans remained in power — which was especially obnoxious considering that the people most vulnerable to conservative authoritarian rule (e.g. marginalized people and the poor) lacked the resources to up and move to a chateau in France. These privileged people weren't just giving up on their country, they were writing off everyone forced to stay behind and suffer. This perspective is coldly expressed when Amanda asks the pessimistic Dan Miller (Jeffrey DeMunn), "You don't have much faith in humanity, do you?" His unbothered response: "None whatsoever."

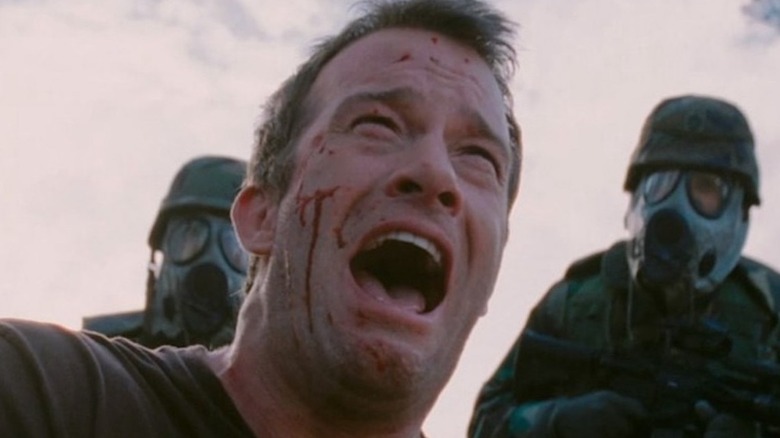

David is fighting desperately to not be that guy. He can't afford to be. His little boy, Billy (Nathan Gamble), is relying on his father to get him back home to his mother. This hope is dashed when David and the surviving quintuplet of himself, Billy, Amanda, Dan, and Irene Reppler (Frances Sternhagen) escape the supermarket only to discover that his wife has been killed. Later, when his car runs out of fuel, the surviving adults, who've seen others die a grisly, excruciating death in the clutches of these Lovecraftian beasts, opt for euthanization via the four remaining bullets in Amanda's revolver. David saves the final bullet for Billy, then steps outside his automobile to face his horrible fate. This seems like a noble gesture until the fog lifts, and he discovers that the ominous rumbling he took for an approaching monster horde is actually a column of military vehicles. Humanity has pulled through. David, who realizes he blew his son's head off seconds prior to their salvation, screams in anguish.

Hope is worth fighting for

Frank Darabont's message is clear: even when things are at their bleakest — when it appears that all is lost — you must never, ever give up hope. You owe it to the vulnerable among us to battle to the last. You have an obligation to the transporting art that's given your life meaning, that's always there waiting for you at the end of a brutal work day, to share it with your loved ones and perfect strangers. Be an agent of enlightenment and joy, and push back without equivocation when privileged, uneducated bigots victimize the powerless. You don't get to quit. You get to fight.

Because when you surrender, that good thing called hope does die, and you will suffer the rest of your days in a desolate mental prison of your own construction.