The Mist At 15: An Oral History Of Frank Darabont's Gut-Wrenching Stephen King Adaptation

There are few movies as divisive amongst genre fans as "The Mist," which celebrates its 15th anniversary today, November 21, 2022. The film was the third of three Stephen King adaptations from acclaimed writer/director Frank Darabont and a massive departure from the classical, more serious stories like "The Shawshank Redemption" and "The Green Mile."

"The Mist" is a story about humanity under pressure and the choices you make when all the chips are down. It also happens to have a lot of creepy-crawly monsters waiting to jump out of an ethereal mist and eat people alive.

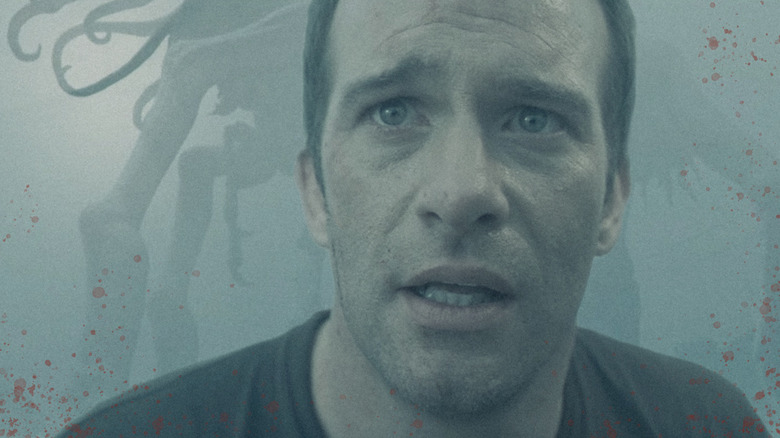

The movie follows David Drayton, an average family man who is both tough and empathetic. He's modeled after movie poster artist Drew Struzan and it's through his eyes that we see what happens when monsters are unleashed upon the folks taking shelter in a small convenience store in rural Maine. David and a small group of clear-headed good guys must try to survive both the monsters outside and the horrific cult developing inside.

To this day, "The Mist" remains a fascinating horror film with a gut-punch ending that will either make you a fan for life or cause you to curse Darabont's name to the high heavens.

I was lucky enough to have spent a week on this set back in 2007 and saw first-hand the creativity, innovation, and care that went into this production. So as the movie celebrates its 15th anniversary, I wanted the cast and crew that brought "The Mist" to life to talk about the entire process, from concept to screenplay to filming, editing, the premiere, and its lingering legacy, in their own words.

Here is the complete story of how "The Mist" was made, told by those who were there.

How Frank Darabont came to The Mist

Frank Darabont (writer/director): "The Mist" called out to me for a number of reasons. One of which is I just thought it was such a potent comment on not just our society, but all societies. We've got this very, very complex technological society and we're becoming more and more dependent on that, by the way. And the more and more we do, the more and more there is this backlash of mistrusting science.

The more we progress into the future, the more there's going to be a part of society that wants to go back to a very primitive, very superstitious [time]. And "The Mist" really spoke to that. It really spoke to the thin veil between how we feel when the lights are on and everything's working fine, and when suddenly we're back in the Dark Ages.

What's scary to me is all it takes is one massive solar flare that comes directly at us instead of off into some other direction of space, and totally knocks out our technology and puts us back into the Dark Ages. If that happens, we're not going to be having a conversation like this on [the internet]. We're going to be out there shooting deer for our dinner and trying to grow turnips in the backyard.

It's such a thin barrier between cooperation and savagery and I just thought it was such a brilliant callback to things like Rod Serling's great "Twilight Zone" episode, "The Monsters are Due on Maple Street," or "Lord of the Flies."

The whole theme of the movie is in this scene where Tom says, "Yeah, when the machines are running and everything's fine, okay." Although even that's getting a little sketchy these days. But turn off the lights, and no lights, no machines, no rules, you'll see how savage people get, and that really struck as true to me. I love when an unpretentious genre movie will actually present a significant theme like that. It's under the donuts and candy, there's actually a very nutritious meal and I love when that happens.

When I was reading it, somehow I just pictured one of those low-budget movies that we grew up all watching. In my case, pre-video, late at night usually on some creature feature. It just reminded me of that sort of '50s, early '60s, low-budget, usually black and white, grainy kind of horror movie. It just felt like one of those things. And that appealed to me greatly as well. So it's a fascinating balance to me between very high-brow and very low-brow elements. And nobody does that better than Stephen King.

So, Darabont reached out to the prolific author about getting the rights to bring "The Mist" to the big screen. Having already impressed King with his adaptations of "The Shawshank Redemption" and "The Green Mile," King agreed.

Darabont: We did the typical dollar deal, and if it gets made, [King] gets more dollars of course.

Darabont is no stranger to King's "Dollar Baby" program, in which he'll allow aspiring filmmakers and good friends to option his short stories for a single dollar. The writer/director's first project was an adaptation of "The Woman in the Room," which ended up putting Darabont on the map in Hollywood and kicked off the whole "Dollar Baby" idea.

Darabont: It was, I think, the first time that Steve had ever done that. It was one of the very first, if not the first. His "Dollar Baby" policy is that it's not to be released commercially. I wanted to make a short film, and try to release it commercially, so the dollar thing turned into an actual option. And it was actually a lot of money for me at the time, but I didn't want to insult the man, so we offered him $5,000 for that. If I'd offered him $2, I'm sure he would've said yes anyway, but I didn't know him that well at the time.

Then years later, years later when I actually had a pretty thriving career, I get something in the mail from him, and I open it. It's that check, that $5,000 check. He never cashed it. I never realized he didn't cash it. And he had it framed and he signed it, "Just in case you ever need bail money." I just thought, I mean, that's just such a great example of the man's generosity and his heart. I can't say enough about him.

I don't believe that the writing [of the script] was a huge job. I think it was more of a pleasure than hauling a sack of bricks on my back, which some writing is. It never particularly came easy to me. My trick, my secret superpower is I could sit in my chair from dawn till dusk. I could write 12, 15 hours a day. I can't do that anymore. Even my knees won't take it, let alone my brain, and I have a life now! [laughs]

Back then, the secret to writing is sit your ass in the chair and do it every day and don't leave unless you have to pee or eat. If you have to eat, do it at home. Don't go out to lunch with friends. Eat and then sit back in the chair again. There's a tremendous amount of work ethic and discipline involved, for me anyway.

I always say to people who've asked in the past, if it doesn't come out perfect the first time, don't feel bad because it doesn't for me either. In fact, my first draft always sucks. My first draft of any page of any script, I look at it and it's a mess. As I go along, breaking new ground, I always start every day with revising the previous set of pages. That gets me warmed up. It makes those pages nicer. So as I start to read them, they don't suck so much. They actually start to look pretty good. Just don't feel like you're failing if it's not the end result right off the bat.

I always had to hack at it for draft after draft. By the time I handed in a first draft of anything, I was ready to shoot the movie because I'd probably revised that page, any given page, 20, 30 times. Sometimes in big ways, sometimes in small ways. For me it was always the discipline. To capture the theme or capture characters or some nuance in the story, that just comes, honestly, as a result of sitting there.

My advice to writers, people who want to be writers and who really want to do good work, is don't think that you get to wait until this inspiration shows up, because it's not going to.

Stephen King has described his muse as a guy with a buzz cut, wearing overalls, smoking a cigar and saying, "Get to work, a**hole. You got stuff to do today. Get to it." And I have to agree with him. If I waited for the airy fairy muse to drop magic fairy dust on me until I'm like, "Oh boy, I'm going to write something great today," I never would've written anything.

The inspiration does not come first. It actually comes during. When you're hacking through the underbrush of the story you're trying to write, that's when it shows up. That's when it happens; sometimes in little drips and drabs and sometimes in a big way, but that's when it happens. You don't get inspiration without it. The inspiration follows perspiration.

Writing the script

Darabont wrote his adaptation of "The Mist" on spec, meaning he didn't have a studio involved when he got the rights. His plan was to write it his way and then shop it around to prospective buyers at the studio level, which was a trajectory that had worked for him in the past.

Darabont: In that sense, it was like "Shawshank," which was purely a spec thing. And thank God I found Castle Rock [Entertainment] at that time in their history. [They had] an absolutely wonderful open door there to filmmakers who had a vision. "The Green Mile" was also for them because there was this tremendous comfort zone with them by then.

By the time "The Mist" came around, they weren't really in a position to greenlight movies anymore. I gather they've recently been funded again as a production company. I sent Rob Reiner a congratulations because I think nobody deserves it more. They were just such a friend to the filmmaker. But no, "The Mist" was definitely on spec. I had the script. We shopped it around.

The difference between a studio budget and an independent budget can be huge. I think I had some kind of overall deal at Paramount at the time, so we had their accounting department budget this thing. They came back with a $60 million budget. I'm like, "Okay, that's not going to work."

I do remember we had one producer who was a very famous producer, and I don't want to embarrass him, so I'm not going to say who it was, but he had a big production fund and he had me into his office and he had a checkbook in front of him. He said, "I'll give you $40 million to make this movie, but you've got to change the ending."

And I said, "What would you like the ending to be? I've been thinking about this movie for 20 years, and there's only one ending I've ever had for the thing. So suggest a happier ending that works. I'll consider it because that's a pretty generous budget."

And he said, "Well, that's for you to figure out." I said, "I'm sorry, sir, but again, I'll think about it overnight, but I'm telling you, I've been thinking about this for a long time and I want that gut punch, that kick in the balls that you got at the end of 'Night of the Living Dead' where the hero is accidentally shot." They think he's a zombie, so they kill him. I'm still reeling from that ending from when I was a teenager.

I sent [the script] to Steve King. I said, "Listen, here's the script. It takes a bit of a left turn at the end." It's inspired, actually, by a line from his book, "But it's not the ending at all that you wrote, Steve. And if you don't want me to make this movie, I won't make this movie. You tell me." I put it in his hands.

And he wrote back and he said, "I read it. I love your ending. I'm sorry I didn't think of it, because I would've written that instead." Right. Okay, great. I take that as a great compliment and an endorsement.

It's a very Rod Serling ending. It's that O. Henry, "screw you, you wanted a happy ending, but you're not getting one but you're surprised, right?" kind of ending.

Again, there's a lot of s*** going on in our country that I was not happy about at the time. Steve King and I share very similar opinions about society, culture, politics, et cetera, so he loved the ending because he got it.

I knew going in that half the audience would hate it. I knew that. But I thought it's art. Not every painting is a happy one. It's an artform of self-expression at its best and you have to run the risk of maybe some people won't like what you did. And that's okay by me.

So anyway, I walked away from the $40 million budget, and the only person who stepped up and had the cojones to greenlight it was Bob [Weinstein]. I got a call from Bob and he said, "I love your script, totally fine with the ending, but you gotta make it for this price," which was a bit less than half of what the other guy was offering.

So I had that night of the soul where I'm going, "Instead of paying myself my directing fee, I'll take scale. Instead of having some luxury of time to shoot, I'll have to shoot on half the schedule." I've never, ever done a movie like that before.

I went to Steve again, because I wanted him to be part of the decision-making process here. I never wanted to make a movie that was going to embarrass him or let him down. I said, "Steve, so here's the situation. The movie that Paramount thought would cost $60 million and this other guy was willing to pay $40 million, I have to make for $18 million. What do you think?" $18 million is not a big budget. Not anymore. Even 15 years ago, it was pretty small. I'm sure that somebody who just made a movie for $800,000 is cursing me out right now and laughing at me, but for the movie we were making, that was pretty tight.

And Steve, bless his heart, he's the eternal optimist. I just love this guy. He responded by saying, "Okay, so take the pay cut. Work for scale. Why not? It's the movie that you want to make. And by the way, there is a great tradition in our genre of working with lower budgets and restrained resources. Go make your low-budget movie." And I thought, "Okay, by God, I will."

I remember when Bob first said, "You can make your movie," and I said, "This is very nice of you, Bob, but we got to have an understanding right off the bat. I'm not some kid out of film school. You guys, no offense, but you have a reputation for taking over cuts and recutting people's work. And I'm not that guy, so if we say yes and we shake hands, then you've got to understand. Of course, you'll be invited into the editing room to watch the cuts, and I will listen to everything you have to say. I may address one note or a hundred notes, or no notes. You've got to understand it's going to be my movie. And if you're okay with that, then let's do it. Otherwise, let's shake hands and part friends and maybe someday work on something else."

And he said, "No, let's do it and you got a deal." That's a promise he made to me. And you know what? I got to say, he lived up to that.

Darabont wrote David Drayton with Thomas Jane in mind

With the movie now set up at Dimension Films with a budget somewhere between $17 million and $18 million, the next challenge was locking the ensemble cast.

Denise Huth (producer): I feel like the casting on this came together pretty quickly, as I recall. Deb Aquila was the casting director on this, who Frank had worked with before and absolutely loves. And she knows him really, really well. So there are always those roles in a Frank [Darabont] movie, we call them the Darabont Traveling Players, who pop up in all of his projects, so we knew Jeff DeMunn, we knew Bill Sadler. There were definitely going to be people who he had kind of earmarked for certain roles in his mind. Laurie Holden was certainly one of them. Even down to Susie Watkins who was his script supervisor for many, many years, but she played, I think the character's name was Hattie. So there's a lot of little roles like that.

For [the role of] David, he really did have Thomas Jane in mind from the very beginning. I'm sure we talked about other people, but Thomas Jane was sort of his goal. He really felt he was perfect for the role, and I think he was.

Darabont: He came to mind while I was writing, simply because I'd always loved his work. He's got a very grounded quality on screen, even when playing that marvelously amped-up extreme character in "Boogie Nights." A lesser actor would have gone over the top in a not believable way, but Tom kept it feeling real.

Tom's got a great working-class everyman quality that I felt fit perfectly with Steve King's world, and with that character. And, boy, did Tom deliver. I loved his performance. The man is a tireless pro, a pleasure on the set, and he really nailed it.

Thomas Jane (David Drayton): Somehow, probably through some dinner, I met Darabont and we sort of bonded on our mutual love for classic comic book art, so we stayed in touch. I don't remember that we were actually actively working on looking for something to work on, but one day a manila envelope was dropped off at my front door. It was a script for "The Mist" with a little note: "Check this out, let me know what you think."

Of course, being a Stephen King fan, I read it right away. And the script was brilliant, in my mind it was definitely up there with the best of Stephen King adaptations. So I guess that's how the project came to me. it was one of those rare occasions where something shows up on your front door that's actually, really special.

It was a very simple conversation. Sometimes these things are, I got to tell you it's rare, but it does happen. Frank is a consummate writer. He is excellent at his job, and of course, he's a wonderful director, very sensitive, very in tune with his version of the human condition. So it's one of those things where I got nothing to say, except for, "Yeah, let's, let's do it."

Darabont: When I was writing the script, I thought, this guy is making every right decision for every right reason, and every decision he makes turns into a disastrous choice and I thought, this is really interesting. This is really provocative because it runs counter to what we expect from a movie.

In most movies. You see your hero, even if he's encountering obstacles or barriers or things kind of go bad, but ultimately they keep making the right decisions and it winds up with the right choices. This is the opposite. And I thought this is a radical departure from how most movies work and how most movie heroes work. In a sense, it is a mirror to reality because sometimes with our best intentions and our best actions, we get screwed anyway because the world is such a messed up place.

If you look at the year I made that movie, look at the world that we were in, the political situation here in the U.S., the cultural situation, the divide that has now become a chasm, was very much in evidence. I was hoping that that wouldn't widen, but it has. So what you had actually was an older filmmaker who was just a little more pissed off than the younger filmmaker who was so full of optimism and hope that he made "Shawshank Redemption." Now I'm just kind of a pissed-off older guy, and that's what I wanted to express.

I think most of us are in the middle of things. Most of us are in this reasonable mass middle of things, but at the edges on both sides, you have this incredibly radicalized, extremist element that is driving the conversation, and it's no longer even a conversation. Now it's a shouting match. Now it's a duel to the death. The extremists are driving the bus and the rest of us have no choice but to ride along and scream in horror as things get more and more crazy and extreme and that was my everyman in that movie. That was David Drayton. That was the character Tom Jane played.

He's the average guy with his heart in the right place making the best decisions he can with the information he has, who gets flattened. And that happens sometimes. Sometimes cultures get to a point where we're rounding up people and shoveling them into ovens. Insanity does prevail sometimes, which is a very, very scary thought. Will it get to that point here? Who knows? I wouldn't have thought we'd get to this point in my lifetime. So is it going to get more extreme from here? Could it? It could, I suppose. I hope not, but the movie worked as a warning shot, as a flare sent up from a concerned storyteller. And I love movies that do that. I love movies that can shake us up a little bit. So that dynamic of [David Drayton] making all the right decisions, but it's going to go in the sh***er was a very conscious thought in my head. As I was examining Steve's story and actually writing my version of it as a screenplay, as I was adapting that, that dynamic became very much at the forefront of my thinking.

Jane: He's making the best choice that he can given the situation and they all turn out to be bad ones, wrong ones.

That was unique. I was like, "Wow, you got the hero of the story and every single decision he makes turns out to be the wrong one in hindsight." I loved that, I loved that.

That's the beauty of it. It's all the choices that he makes the audience would've made, too. In other words, we buy all of his decisions as being the best option, the "right" thing to do. He does all the "right" things to do, which will turn out to be wrong. And I think that's a wonderful statement. And I think it's a large reason why the movie, even if it's just on a subconscious level, that's why the movie's successful.

The trickiest role was in the most capable hands

Huth: I think there were a lot of names discussed for Mrs. Carmody because that is probably the trickiest role in the whole movie. She very easily could have been way over the top. It could have just been a caricature and it was very important to Frank, and to all of us, that character be as grounded as possible.

She obviously gets very extreme very quickly. And even when you first meet her, you feel like, "Oh, maybe this woman isn't quite all there." But to her, it was very real. To her, this is what she truly believed. It's not just that she's a lunatic, it's that this is her faith and this is what she truly believes. This is not somebody who's trying to be the bad guy for the sake of being the bad guy.

And when Marcia Gay Harden came up, I think it was such a great idea. It was probably [casting director] Deb [Aquila]'s idea because most great ideas when it comes to casting come from Deb. She brought that humanity to it. She brought that vulnerability to it. She's just not this evil witch of a woman. She's scared. You see her in that scene where she's praying in the bathroom and she's crying and she's scared. And that really is the cornerstone, I think, of the whole story, which is what do people do when they're terrified, and how do they react? And everybody's going to react differently. She clung to her faith, and that became the thing that was going to carry her through.

I think she's so fascinating to me, and the whole fact that so many people, including the Bill Sadler character who completely switches sides from starting out, like, "You're a nut, shut up," to being one of her true believers.

And with the mist, it's so unknowable, but she's giving them something to cling to. She's giving them a reason. She's giving them someone to blame. And that I think makes people feel like they're more in control of an uncontrollable situation.

She committed to it 100%, which is huge. I don't know that Marcia Gay Harden was necessarily an actress at that time going, "Oh, you know what? I want to do a monster movie." But she really understood it. She understood the story Frank was trying to tell and really saw who Mrs. Carmody was and embraced that.

Darabont: There was no great search for Mrs. Carmody, or for Brent Norton. It was as simple as their agents calling and asking if I'd be interested in working with Marcia Gay Harden and Andre Braugher. My response? Are you kidding me? Yes, please, and thank you.

What a pleasure it was to work with her, and let me say the same about my entire cast. Andre Braugher! Toby Jones! Sam Witwer! They were all new to me as colleagues. Every time I think of those people and the great experience I had with them, I get a warm glow. And of course, that also goes for the cast members I'd worked with before: Jeff DeMunn, Laurie Holden, Bill Sadler, on and on. I'd hang a medal on each and every one of them.

Assembling the key players

Darabont: Laurie [Holden] is another marvelous talent, a pro who brings so much texture and heart to whatever role she plays. I adore fearless actors, and she's one of them. I loved working with her on "The Majestic," so I wrote the part in "The Mist" for her. Ditto her role in "The Walking Dead." Those roles were hers, I never auditioned anybody else. That same goes for any time I ever cast Jeff DeMunn, or Bill Sadler, or others I worked with multiple times. When you know you have the right actor for a given role, you count your blessings and go with it.

By the way, Laurie's role in "The Walking Dead" was intended by me to have a substantial character arc that never transpired. She would go from being a mentally jangled, super self-absorbed, badly traumatized and angry girl to the opposite end of the spectrum: their most reliable soldier, an ace sniper, and a grown-ass woman who becomes all about self-sacrifice and protecting the group. And her relationship with Dale would blossom into a very deep May-December situation, a real marriage based in deep abiding feelings and respect. I aim for characters and situations based in messy and complicated feelings, as happens in life. And no, she was never intended to be a love interest for Rick, as I read somewhere.

She was never meant to be thrown away as zombie food. Nor was Dale, for that matter. Nor was Glen.

Nathan Gamble (Billy Drayton): We had to record [my audition] on a tape, an actual tape, and we had to send it off and it would take three days to get there. It took a long time before we knew anything. I never actually had an in-person audition with Frank or any producers or whatever.

The tape that I did must have been good enough where they didn't need to because I was in Seattle and I did most of my auditions that way. I remember even as a kid, most of the stuff where you would audition through tape, they watched it and they'd go, "Okay, let's fly him down to L.A. so they can meet in person and see his look in person and yada, yada, yada." But no, this was a pretty straightforward process. It was bada bing, bada boom, there you go, you got it. Now you're in a Stephen King movie.

Andre Braugher was approached to play David Drayton's neighbor, the uptight and petty lawyer Brent Norton who ends up joining David Drayton and his son on their fateful trip to the grocery store. He didn't remember the process of being cast, but did remember the impact the script had on him.

Andre Braugher (Brent Norton): It's a good script. It's a very humane script, as horrible as it is. These are all people who react in a very understandable way to shocking events that really upend the way that they think about the world.

It also reveals what people turn into in extreme situations, like Marcia Gay Harden's character, or what Thomas Jane is ultimately forced to do at the end of the film. You know what I mean? These are ordinary people under extreme stress. I found that to be a fascinating part of the film and the character that I played.

Stephen King has done a wonderful job writing this story, and Darabont has done a wonderful adaptation that shows, essentially, ordinary people trapped in the grocery store by the mist, and how fascinating that is.

Darabont: Alexa [Davalos] is a fiercely talented actor who projects such intelligence in her work. By the way, I've known Alexa since she was a toddler. Literally. I attended Hollywood High with her mom, Elyssa; we were in the drama department together.

I first cast Alexa in the pilot episode of "Raines" that I directed for its creator, the wonderful Graham Yost. She played opposite Jeff Goldblum, another actor I loved working with. I adore that guy. He's freakin' brilliant and a total blast on the set.

Later on I wrote the role in "The Mist" for Alexa. After that I wrote the female lead in "Mob City" for her opposite my man Jon Bernthal, and man did she shine. Her work in that actually awed me; talk about nailing the perfect period noir vibe. She was like Gene Tierney or Jean Simmons reincarnated.

Sam Witwer was on his way to another audition

Sam Witwer (Private Jessup): The way that I walked into "The Mist" was, well, steeped in ignorance because not only had I not read the short story, but I wasn't even supposed to audition. It was all completely an accident.

I was walking down the street in Hollywood and this woman is on the crosswalk, carrying bags of stuff and she dropped everything she was carrying.

No one was going out to help her. I remember some guy walking next to me actually snickered, which really made me angry, so I ran out into the street, said, "Hey, can I help you?" And she goes, "Oh, please," because there were cars coming and stuff like that. So, I helped her pick her stuff up and I said, "Okay, where are we going?" And she goes, "Right over there." "Okay, cool."

And we got into the elevator with her stuff and I guess I had my headshot with me because I believe I was going to her office anyway for an audition that I remember utterly not being excited about. She saw my headshot and she goes, "Are you an actor?" I'm like, "Yeah."

So then, we go up in the elevator, and we go to this casting office. I'm like, "Oh, I guess this person works at the casting office that I was heading to anyway. Well, isn't this convenient?" So, this woman says, "Hey, everyone. This is Sam. He's an actor. Oh, Sam is so nice. He helped me pick up the stuff in the middle of the street. Let's buy him lunch."

And I was like, "Whoa, my lucky day. This is great." I'm a young actor, right? Free food is awesome. That's the best. And then, she goes, "Actually, instead of lunch..." And then, I'm like, "Oh, I guess I lost the lunch before it even happened." She goes, "Would you like to read for something?" And I said, "Sure."

And so, she handed me these scenes. One was the romantic scene between Jessup and Alexa Davalos's character and one was an argument scene which would eventually be the scene with me arguing with Tom Jane. And then, one was this freaking out crying scene where I'm accused of all this awful stuff. I had no idea what it was. And I had about 15 minutes to sit down and look at all this material, including the freaking out crying scene.

And I looked it over and I was like, "Okay, I think I got the gist of it." And then, I went in front of the camera and performed it. And I remember Deb getting very excited and her saying, "Oh, my God, Sam. You might really have saved me on this and Frank is going to love this." And I'm like, "Great. What is this? Is this a TV show?" She goes, "No, it's a movie." I'm like, "Okay. Well, thanks, Deb. Thank you. Bye."

So, I went down to my car. Got into my car, called my manager and I said, "Listen, I just met someone named Deb in the middle of the street. I auditioned for something. Apparently, it's a movie. And apparently, someone named Frank is going to love this. Do you have any idea what the hell just happened?"

And my manager goes, "Okay, I'm looking this up. Well, that casting director, that's Deb Aquila. She's a big casting director." I'm like, "Oh, well, that's good." "So, that movie, that would be 'The Mist' probably." And I'm like, "'The Mist' like Stephen King's 'The Mist?'" He's like, "Yeah, and the Frank ... looks like that's Frank Darabont." I'm like, "Wait a second, 'The Shawshank Redemption,' 'The Green Mile' Frank Darabont? 'Dream Warriors' Frank Darabont? Come on, 'The Blob' Frank Darabont? 'Young Indy?'"

So, I started having a freak out at that point. I was so glad that I didn't know that when I actually did the audition. And then I got a call the next Monday saying, "Frank Darabont would like you to be in 'The Mist.'" So, that was it.

But the story is even a little bit cooler than that. I think it was a week or two before I auditioned for them, this guy named David Scow handed Frank Darabont DVDs for a television show called "Battlestar Galactica", which Frank was like, "I'm not watching 'Battlestar Galactica.' Come on. The rehash of 'Star Wars?'" And David Scow goes, "That's not what this is, man. You got to check this out."

So, Frank did check it out, lost his mind for it. The story Frank tells, he knew nothing about bumping into Deb on the street, none of that. None of that story got to Frank.

The story Frank told me back was, "Oh, well, here's my version. I was on the treadmill. I popped in the casting tape, got on the treadmill. And it started playing, and your audition came up. And I said, 'Oh, my God, it's Crashdown from 'Battlestar Galactica.' Cool. Oh, wow. He's really good. Oh, he's really right for this.'"

And then he said, "I got right off the treadmill, hit stop on the tape, called up Deb, and said, 'Hire that guy.'" And so, I'm like, "That happened that fast?" He's like, "Yeah, it's happened that fast. I literally got on and off the treadmill."

So, that is the story of how I got "The Mist," the multifaceted, multi-viewpoint story.

Melissa McBride stunned everyone on set

Melissa McBride (Woman with Children At Home): I was working behind the camera in casting at the time, and I'd gotten a call about the Darabont project from the casting director that I worked with quite a bit. I had been in casting for a while already then. There was some concern that I wouldn't be able to do it because the role that they wanted me to audition for was in the store for the entire run of the production and had one word of dialogue, but I had a full-time job.

I remember at the audition seeing the sides for that other part, and I read them and I was like, "Well, what's going on here?" I thought, "Well, she goes out of the store, maybe she gets killed." So that's a quick part and that's a really juicy little monologue.

Darabont: She was one of the helpers there in the casting office. They threw her on just to have one extra choice for one role that had one line of dialogue. It was something along the lines of, "Oh my God, you killed her," or, "you murdered her." I think it was one of Mrs. Carmody's ladies. And she literally did this one line of dialogue on the tape. And I remember we were still prepping, but I was there on-site. We were in Shreveport by then and I saw her say this one line and I went, "There's something really special about this actor." So I immediately called the casting office and I said, "Could you please have her read for the bigger role for the lady with the kids at home?"

McBride: I got a callback and was asked to read for that part, coincidentally enough. I did and that was the role that I ended up getting.

Darabont: It was just a home run audition. I was so surprised that she hadn't been put forward as a leading contender, a leading possibility. I was so thrilled to find her because I knew that we needed an actress who could really deliver that scene. And boy, did she.

So when "The Walking Dead" came around, I just said, "Okay, I'm casting Melissa McBride." And I didn't even talk to her about it. "I'm casting Melissa McBride." Carol is her role. And everybody said, "Yeah, okay."

And the next thing she knew, she's what, in a decade-plus of this hit show? I'm just so proud of her. She's such a naturally gifted powerhouse of an actor and I'm just so pleased for her.

She said to me she'd pretty much given up even trying to be an actor at that point. They just put her on as an afterthought just to have one extra choice. And it can turn like that.

There's no place like Shreveport, Louisiana

While the production team was casting their ensemble, they also had to suss out a location to build their supermarket that could feasibly double as rural Maine. The location they settled on didn't exactly wow the cast and crew.

Huth: I would think we probably looked at a few different cities, a few different states. Story-wise, it takes place on the East Coast, but my guess is it was pretty much driven by where can we go where we can own a stage for that long, and that has a good film crew base.

That was a time when Louisiana was a big Mecca for filming. Moreso New Orleans than Shreveport, but Shreveport had stuff going on and the stage was available, so I think that was the majority of what went into it.

There was crew. That's a key part of it. You can't just go anywhere on location if you have to bring an entire crew with you. If they already live there, that goes a long way. It's part of why Georgia is so big right now. There's a huge, huge, huge film base there. And that's why so many movies can be filming there at once.

Rohn Schmidt (cinematographer): I'm glad we were shooting six-day weeks because it just got us out of there a week faster.

And not just me, but many other filmmakers have spent a film there and it's sort of like doing your time. It's like, "Oh, you've worked on the frontline if you've shot in Shreveport." So anyway, there were nice enough folk and I certainly don't want to call it a s***hole, even though I've never had any desire to go back.

I don't know if Frank remembers this, they wanted to shoot the film in Toronto. They were almost ready to start construction on the set up there. The show is set in Maine, so it probably would've been a slightly closer match than Shreveport, Louisiana, but the union in Toronto would not let both [camera] operators come.

Frank was not going to give in on that. I guess they didn't believe their bluff would be called. I don't know the politics of all of that, but Frank said, "Okay, we'll just go down to Louisiana and use their tax breaks."

It became a running joke because Shreveport's fine, but it's not a very big city, certainly not on the world-class scale that a city like Toronto is. Each Sunday night when we went out to dinner, we'd go, "Okay, well we could be going to a fancy restaurant in Toronto, but we're going to head on down to the Applebee's and get some dinner tonight."

Jane: There was nothing around. It was pretty lonely out there. It wasn't even really a town, it wasn't a decent place to eat. At one point about halfway through the shoot ... I don't know if you were there for this, but I'm a big fan of crawfish and I found this place in Nacogdoches, Texas, right over the border, and I bought a couple hundred pounds of crawfish and had them shipped in for the crew one day for lunch. They showed up and we put them in a big canoe, God knows why.

Anyway, we had this whole canoe and it was full to the brim of crawfish and I treated the crew and myself to really excellent, succulent crawfish one day. I'll never forget that, that was a really fine crawfish. If you're ever in Nacogdoches, look up the crawfish there.

Huth: I do remember he brought crawfish. Shreveport is not New Orleans, for sure. I also remember we were very close to a dog food factory and so it smelled like dog food 24 hours a day. Nothing against Shreveport, I'm sure there's lovely things in Shreveport, but just where we were, it was not a place you just want to go for kicks, I guess.

'Jazz improvisation' and working with the crew from The Shield

Darabont and his producers had their location (with the all-important tax breaks and good crews) and their big cast, but one problem was evident: they were still attempting to shoot a script originally budgeted at $60 million for around $18 million. This forced Darabont to scrutinize his usual slow and steady production technique.

Darabont: I couldn't be the Kubrick wannabe, like the painterly director on "The Green Mile" or on "Shawshank." I had to really shoot from the hip for once.

Thank God for Shawn Ryan and "The Shield." He found out I was a big fan of the show, which starred Michael Chiklis and an amazing ensemble cast. It's one of the best TV series ever.

He found out I was a big fan of the show because my friend and casting director, Deb Aquila, had cast "The Shield," so she mentioned I was a big fan. He said, "Does he want to direct an episode?" I said, "Oh yeah, why not? I'd love it."

Most hour television shows don't actually have an hour. It's 42 minutes, for crying out loud. Commercials take up a third of the running time for commercial television shows. You [typically] have eight days to shoot [an episode]. "The Shield" had seven.

Schmidt: "The Shield" was originally intended to go to Canada and to do it on the budget that they had set aside for a Canadian production. We had to cut one day from the production, so rather than the normal eight days for an hour episodic, we had to do it in seven. That was part of the deal going in. Everything had to be 12% faster to achieve that.

One of the ways we came about that was with zoom lenses, not spending time on lens changes. Robert Rodriguez's "El Mariachi" had come out and he had a rather ingenious idea where he would start out a scene wide and then would zoom in about a third or halfway through, knowing he was not going to go back, editorially, to that wide shot. So we were doing the same thing. We would roll for a little while, and then when someone wasn't speaking, we would zoom in to the next lens size.

I think I lost half of my hair in my head when I saw the first edit of the pilot, because they had used those zooms. They were never intended to be used on camera by me. I don't mind admitting this. We were just trying to be efficient and I'm like, "Stop. You got to cut all those out. They're terrible. They're rough and they go in and then they adjust again a second time and the focus is there and the person's not even speaking."

And Scott Brazil and Clark Johnson both went, "No, that's what's great about it." And what they discovered is because they were on someone not speaking they were emphasizing what someone was hearing. It was about the actor's reaction there. And it made it much more powerful to hear the words and then emphasize that actor's reaction by zooming in on it and it became really iconic to the show.

Darabont: I went, and I directed this thing, which was the easiest directing I've ever done, because that crew and that cast were so dialed in. It was such a smoothly running machine that it was ... I wouldn't say it was quite like directing traffic, but it wasn't much harder than that because those folks were such pros.

I hired the two camera operators and the cinematographer. They had a hiatus coming up and I said, "You want to come do a movie with me in Shreveport?" And they said, "Sure." And Rohn Schmidt, who was the DP, I mean, this guy could light a scene in 10 minutes. It's unbelievable.

This is a movie where the lighting didn't need to be pretty. If you were harkening back to the tradition of "Night of the Living Dead" and movies like that, the lighting wasn't pretty. It was very documentary-like and Rohn was brilliant at that.

What was truly amazing were the two camera operators, Billy Gierhart and Richie Cantu. These guys had years of experience on "The Shield." And all their coverage on "The Shield" was improvised. They'd get in there, Billy with his steadicam and Richie sitting on a skateboard with a camera on his shoulder and just, from take to take, they'd do whatever interested them. Wherever the lens took them, that's how they shot. So every take was different.

Schmidt: [Frank] calls it jazz improvisation and I think that's a very perceptive way that Frank has described it. You have the baseline, you have the melody that you're referring to, that everyone knows the story there, but then they just go and react to what the actors are doing, react to what the other camera's doing. The two operators would often have their [other] eye open, looking to see what the other person was doing just to make sure they weren't shooting the same thing.

Witwer: The camera crew were characters in the movie. They were participating in those scenes, so there was never a moment where you could slack off and feel relaxed because you weren't going to be on camera, because maybe it was going to be your close up. You had no idea.

Jeffrey DeMunn (Dan Miller): That was really neat. Initially I went, "Huh?" And then I realized how superb it is because you don't have to play to anything. You just do the scene. Those two guys were like a pair of ballet dancers. Oh my God, they were the most elegant dancers together moving those cameras around and you just talked. You just said what you had to say to the other person and they would make the shot up. It was really delightful. I don't understand why I haven't encountered that more often.

Braugher: That whole thing started with "Homicide," so I was very familiar with it. The role itself had challenges. You know what I mean? Being cooped up in that supermarket was tough in and of itself, but in terms of the shooting style, I felt very comfortable with it, because I'd spent six years on "Homicide" doing that in particular. It was like going home.

Jane: Me, I was a fan of "Shawshank" and "The Green Mile," and I was disappointed that Frank had decided that he was going a different way with "The Mist" and shoot it in this much more kinetic style of filmmaking. I'm a big fan of that classicism that he used with "Shawshank" and "The Green Mile."

So I was disappointed. I was like, "God, I wanted to be in one of those kind of movies," and I told him as much. He said he'd done a couple of episodes of "The Shield" and he really enjoyed the speed and the quality of the filmmaking that the style of "The Shield" had.

The B-Camera operator had a stool. He had a handheld camera and he had one of those office stools that you can kind of roll around using your feet, with very smooth wheels. And he sat on that f***ing thing and scooted himself all over that grocery store, getting different shots.

And I thought, "Oh, great. This is going to look like an episode of television," but it didn't of course. I thought that kinetic energy worked very well for that contained story. I thought it was a good choice.

We worked financially constricted because Bob Weinstein wouldn't give us more cash because he was terrified of that ending, but the decision to use the crew from "The Shield" still served a version of the story that works for the story. He was able to make it work, and yeah, I was disappointed, but in the end I thought the artistic choice was sound.

The original opening didn't make the cut

Another victim of the tight budget was the original scripted opening, which took us inside the Arrowhead Project and gave us a concrete explanation on where the mist came from.

Darabont: It was basically a scene where they're trying to open a portal into another dimension and suddenly the chamber, that I pictured as an old diving bell with portholes and stuff, suddenly the glass blows out and this mist comes pouring out and this chaos and screaming and then boom, we cut to the opening title and then the rest of the story goes on as you see it in the movie.

Schmidt: I loved the location. I was looking forward to shooting that because he found this cool [place]. I think they used to defuse and grind up Nike missiles or something like that, this absolutely absurd '50s actual place out on that military base. I still have some of the stills from there and I just jaw drop every time it comes up. So it would've been a really great sequence, but yeah, I think it over-explained it.

Braugher: I remember Frank was talking about, "We're behind schedule. I got to film this thing with the army." I suggested to him, I said, "You don't have to film that thing. It would be best not to film it." He was intrigued. He said, "Why?" I said, "Well, if you know that the army did it, then that means that everyone in the storefront who's speculating about its cause, we already know that they're wrong. So we're ahead of them, as the audience." So I said, "You can actually gain a day, and I think make a better movie, by not filming that rather than filming."

Darabont: I remember when Andre got to Shreveport, we got together just because I'd never met the man. I was so thrilled he was coming to do this movie because God, I admire him and his work. So we sat down together over coffee or lunch or something and I love to pick my actor's brains. What do you think? And he says, "Well I love the script, but do you think you need that opening?" And I went, "Ding!"

It was at this point that I gently reminded Darabont that when I was visiting the set he also asked my opinion on whether or not they should cut the opening scene. My response to the question was that King's story didn't need the explanation and ultimately it'd be scarier not to know where it came from.

Darabont: By all means, take credit because now that you mention it, I vividly remember that. I hadn't thought about that in years, but yes, I do remember that. And when you said that if you don't know where it came from, isn't it a little creepier? I thought, "Oh, that's right. That's pretty good." As you said, Stephen King's story didn't need it, so where did the mist come from? Who knows? And we actually get a pretty good explanation from Sam Witwer, another actor who I loved working with, or did back when I was working. You get that explanation from that character.

Witwer: I didn't feel like we needed it, but I was afraid to bring it up because A, I was this young actor, didn't have any right to be making suggestions like that, and B, I was also keenly aware that it might be self-serving. Because I looked at that and I said, "Well, if you had this opening thing in the movie, do you really need Jessup?"

One of his functions is to give a piece of an explanation as to what's happened here and to do it at a really interesting point in the movie. If you get that full-throated explanation of where the mist comes from in the very beginning of the film, doesn't that make Jessup a little bit redundant? I'm trying to not get cut from the movie. You know what I mean?

Braugher: [Without the opening] we have to ask ourselves, is this the Lord at work? Is this retribution for crimes and sins? Is this that experimentation that they were doing over there like the soldiers were suggesting? We never know.

Darabont: I loved that opening and I loved the sort of low-tech, high-tech production design that I had in mind. In this last season of "Stranger Things," when we're in the underground facility and there's these crazy machines that all look like they're pounded together out of cast iron and rivets and stuff, it's exactly the kind of production design I had in mind for the opening of "The Mist."

I just really wanted to shoot that sequence and wanted to do that low-tech '80s sci-fi vibe that The Duffers have now perfected, clearly, but the truth is, I didn't have the money to do it. I didn't have the three days to shoot. I had $18 million to shoot and about, gosh, what was it? 34 days to shoot. "Shawshank" was a 71-day shoot. "Green Mile" was 105-day shoot. This was a 30-something-day shoot.

To shoot that, I mean, and really actually do it right, would've taken certainly at least two days to shoot. It just wasn't in the budget. We didn't have the resources. We didn't have the money to build that set. We didn't have the money to hire those actors. When you're dealing with that tight number of resources, you have to pick your battles.

Starting on the loading dock

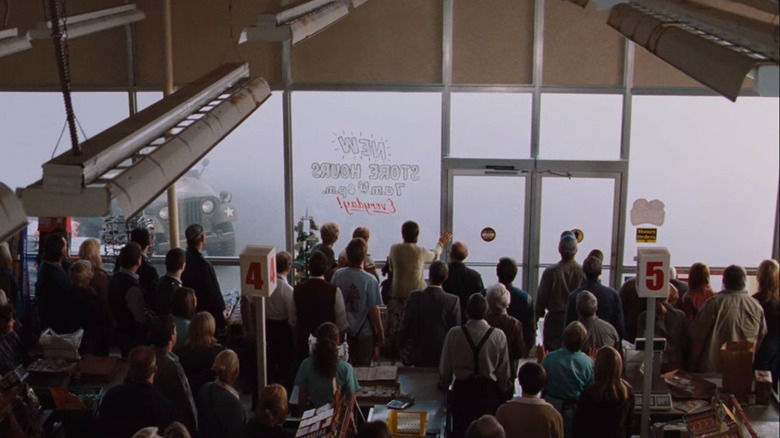

The first scene to be filmed was the loading dock sequence in which our heroes explore the back room behind the store, a scene that would culminate with poor Norm the Bag Boy (Chris Owen) getting dragged out into the mist by tentacles. It was something of a rocky start.

Schmidt: Our first day of shooting was in there and I had made a big promise to myself to go for it on this film, to not be afraid, to just hang it all out, be on the edge and not be safe at any point.

[Thomas Jane]'s walking around lighting the scene with just the glow from the cell phone, which was very new at that point that you could do that. We worked with the props department to rig out a slightly brighter LED on the cell phone to make that all work and it looked beautiful. It was right on the edge in terms of exposure or not, but it was very cool looking.

This is [shot on] film, so the negative went off to Los Angeles to be processed and transferred. I talked to the color timer later the next day, midday, "Oh, it's absolutely beautiful, spectacular. I can't believe how cool looking this is." I'm like, "Okay, great."

And that night we were going to watch the first day's dailies and they had set up a little video projector in one of the conference rooms at the hotel we were staying at and everybody's there and they've got beers and little pieces of pizza and they're all ready to watch the first day's dailies.

It turns on and all you can see is just the white square of the cell phone. Absolute black except for this tiny little white square of a flip phone and it never gets brighter.

And we're becoming aware that slowly everyone in the room has snuck out one by one. So it's just me and Frank and Randi [Richmond], the producer. We turned on the lights and looked at each other.

I said, "Well, Frank, I guess you need to replace me because that's not acceptable." And I said, "There's another cinematographer I know that's very competent." He was finishing up in New Orleans. I think they're finishing that week. I said, "I'll call [him] and he can come finish up for me, or if you want me to hang out and try to do my best for the next day or two until we can get someone in from out of town, that's fine. Whatever you want to do."

And they said, "Okay, well, we'll just reshoot and we'll figure it out," and we went to bed. I had a long talk with my daughter in the parking lot, "Well, I think I'm going to be home a lot sooner than I thought I would be."

And about 11:00 P.M. that night, I'm very much in bed because we're shooting again at 7:00 am the next morning. And then there's knocking on my hotel room door, "Rohn, Rohn, get up," and it's Billy, the camera operator, who's a techno-geek. He sleeps about four hours a day anyway and says, "Come down, come down."

Apparently, the digital projector that we were viewing these dailies on was not set up. No one had ever calibrated the projector. We sat and watched and it was beautiful. It was all there. It was spectacular.

We did reshoot that day's dailies there, although I think the original footage is what's in the film because I was so gun-shy that it was way overlit when we went back in there. I was going to make sure we could see what we needed to see there.

The practical problems with practical effects

That scene also presented an interesting challenge for the practical effects crew.

Huth: Greg Nicotero was one of the first people Frank called when we found out we were actually making the movie. Greg and his team at KNB EFX designed so much of the creature work and actually built models of a lot of it; of the tentacles, of the bugs, certainly the spiders. There were a lot of the creatures that they had, practical things built to scale for us, which we could use in some shots.

I remember the tentacles being one of the hardest things just because of the way they move, and the interaction with the actors and the physical world, with the loading dock door and all of that. I remember we had some practical, but most of that I think ended up being visual effects. [That's] just the nature of how the effects work.

We didn't have the time that practical effects always take. Everybody prefers seeing something real as opposed to something digital and there are some moments in the show with real spiders that Greg made and the real bugs. It is also hugely helpful for the actors to see, just to really understand what they're looking at and what's going to be animated in front of them when right now they're kind of staring at a blank space for the spiders. I remember the special effects guys had a mop and they were just backing away from camera with it and it would be replaced by the bug. In a perfect world, you do everything as practically as you possibly can. But we don't live in a perfect world, we live in a filmmaker world and you gotta make it work.

So I think the visual effects turned out pretty amazing, all things considered. And they work well together. And I think that's the best kind of effect is when you can match a practical effect to a visual effect and make it pretty seamless.

Gamble: My mom and my dad, trying to preserve the innocence of a child as much as they could, they only allowed me to read the stuff that I was in. There's some pretty graphic stuff in that movie and pretty gory stuff. This one time I was on set, oh my gosh, I was a fish out of water. I was walking towards lunch because they just called lunch and I forgot what his name is in the movie, his character, but he is set on fire and his whole body is just maimed with crazy third-degree burns. He had all this incredible makeup on that I, at the time as a stupid 8- or 9-year-old didn't know it was makeup. So I see this burn victim walking at me and my heart just dropped into my britches, man. I could not fathom what I was looking at. My mom had to calm me down. It was probably comical looking back on it now, but pretty traumatizing as a kid.

I think it needs to be recorded how much of a standup guy [Greg Nicotero] was to [me] on that set. He thought I was a cool dude as a 9-year-old. I remember him showing me these various things, bringing us to the various prop tables and he just made it seem like it was all fun and games and you did not take it very seriously, because that was a very serious heavy set.

But yeah, Greg, especially, he was a rock star. He was cool.

The special effects crew knew they wanted to keep as much of the mist itself as practical as possible, so they devised a way to exert control over the actual mist itself.

Schmidt: Special effects person, Darrell [Pritchett], had worked that out, tested it out with just positive air pressure and chilling the mist. He just walked around the set with the little remote control and he could literally just bring the mist in or push it back out just from standing there right on the set. It was really pretty remarkable.

Huth: I remember that stage was freezing. It was freezing, freezing, freezing cold. And it had to do with the temperature of the room and the temperature of the mist, and that's how they could manipulate it like that. I believe that was all practical in the final movie. I don't think they augmented that at all. That's one of those things that you can do practically and make it look amazing.

[...] I think that it was augmented a little bit when we were outside. When we were filming in the grocery store, basically half of the stage was the store and the other half was the parking lot. And the parking lot side of it, anytime we rolled was completely filled up with mist if we were shooting out those windows. And that was just part of the set.

Controlling the movement of the mist was one challenge, but actually shooting usable footage within it was another.

Schmidt: What was discovered is that it really had a lot to do with how it was not only lit in photography but also how the final finish, the final color correction, coloring of the show was there. It's almost like night vision, you can see into the mist if you drive too much contrast into there. That was the style there to have lots of contrast in photography, but really what the secret was was to reduce the contrast and that gave it that milkiness that was always there and obscured. It's so dramatic to see people walk off and disappear into that mist. It's pretty creepy.

We were very careful about it. We'd be very still and [ensure] that there weren't puffs or clouds for the most part. If you think about it, it's just there. It didn't feel like it was moving around. Normally, I would prefer that you feel the atmosphere dancing, but that was really neat just to see it just hanging there. "Okay, this is just a weight hanging over us all the time." If there's clouds, a breeze, it would almost imply that it was going to clear at some point, but nope, not going to happen.

There were times they had it pumped in there so thick that you couldn't see your feet and it was weird. It's vertigo at that point.

Melissa McBride's monologue

One moment that nearly every person I spoke to brought up was the moment where Melissa McBride wowed everyone on set with her monologue, where she begs for someone to help her get to her children who are alone at home. This happened early on in the filming schedule and took everybody by surprise.

Huth: I remember when she came on set and did the scene, everyone was just so blown away. It's such a tiny little moment, but Melissa's a unicorn, she can do anything. And she still is, after having worked with her for 12 years on "The Walking Dead," she's just so incredibly talented and so tapped into emotion. And it plays so real. She's one of the most natural actors I've ever seen. It's just incredible what she can do. And nobody knew who she was. She had certainly worked before that, but it was all tiny little roles similar to this one.

Jane: Yeah, I remember her murdering it. The hardest job for an actor is to be a smaller character who basically flies in during the middle of some shoot and you've got a day, maybe two days, maybe half a day, and then you fly out. So you're jumping onto a moving train and then you're jumping off of a moving train. That is the hardest job for actors. It's very difficult to find competent character actors who come in for parts like that. When you do find them, it's that much more impressive, to watch somebody jump into something, come in, knock it out of the park and then leave. It's f***ing great.

Schmidt: We were all in tears, and I'm not just saying that like, "Ooh, it was a moment." We literally were choking back tears because it was such a perfectly impassioned speech. I'm not sure she even has children, not that I'm aware of. Maybe she does now. At least at that time, I don't know if she did. And yet, you just felt that absolute care. And again, it's just one of those monologues that was written that could have been quite sappy, but it was just so genuine. And that look she gives them before she heads out that she gives everyone there is like, "I can't believe you people." It just touches on the humanity of all of that.

Witwer: I think she did it maybe three times or something like that. But to deliver it and have it be perfect each time and have the camera crew also doing their jobs each time, it was just an incredibly unpredictable ballet that you watched in front of you. And it was very intimidating to watch because it was so well pulled off.

Darabont: What a courageous actor because you have to do this wrenching emotional thing and there's literally over 100 people watching you. There's 80 extras, there's all this crew. She just totally dialed in, totally nailed it. And people were blown away by what she did. And yes, burst into spontaneous applause, that does actually happen.

And I remember about halfway through the coverage, Jeff DeMunn kind of sidled up to me and said, "Who is she? Where did she come from? Did you fly her in from L.A. or New York?" I said, "No, she's local." And he said, "She's astonishing." He was absolutely blown away by what she was doing.

Gamble: We all clapped afterwards. At the time no one really knew who she was. She wasn't this huge action star in "The Walking Dead." So she knocked our socks off.

I remember Frank being at the monitor. He couldn't believe what he was getting because it's an important scene. She's probably one of the best actresses that I've ever had to work around. I didn't really have any close interactions with her. I mean, we talked and she was very friendly and nice, but it was definitely one of those scenes where it was like, "Dang, this lady is a legit one-take wonder." We don't need to ever do that again, ever. Everything you needed was in that one take and the whole crew and cast clapped for her afterwards.

Time is money and the director usually comes up and says, "Hey, great job. We're going to move on," but everyone stopped for a good five, 10 minutes and just showered her in praise.

McBride: I have stage fright. I get the irony of that. I guess the intimacy of film makes it somehow different, but I learned early that I had stage fright from school and public speaking, all of that stuff. Obviously, it felt good to know that people liked the performance. It was also strange because I've been on several shoots and have never experienced anything like that. It was unusual. I thought it was unusual and it was a little out-of-body feeling for something like that to happen.

'They'll come tonight'

One of the most challenging sequences to film in the entire production was the nighttime attack where all hell breaks loose. Poisonous bugs break in and are chased by big pterodactyl-like creatures that then turn on the humans hiding in the store. There are practical fire effects, digital effects, gunfire, and child endangerment, and all at night. Scene 35, as it was dubbed in the script, was so notorious that Constantine Nasr built a whole DVD featurette around it.

When there's chaos on screen, that usually means every element behind the scenes was perfectly engineered and planned to the smallest detail to get all the right pieces. But the tight shooting schedule and kinetic style forced Darabont and his crew to shoot from the hip.

Darabont: We were shooting very specific things because there were special effects that were coming into it and I needed the scene to cut together. Instead of looking at the storyboards, I was just making it up as I went along. I was going, "Okay, now we're going to shoot this. And then we're going to shoot that. And then here's how it'll cut together."

That was a week of this madness. It was a runaway horse, but we held on and we got the scene in the can. And I was very, very proud of that, and really pleased with that. Man, I had fun. As much as it was incredibly exhausting and stressful, because you're shooting a movie in half the schedule you've ever shot a movie on.

Gamble: There's that one dinosaur-ass-looking thing that is stomping its way towards me and then Tom's character pulls me aside at the last second and then it gets blasted away by Ollie.

Well, when Tom picked me up, he tripped on the edge of an aisle and me and him fell. I fell head first in his arms, right on the ground. I banged off of the sections of the aisle, and then I banged my head on the ground. I remember I didn't cry or anything, but I had a bruise on my head. I remember that.

I had worked with the same producers of that movie actually on another TV show and I had a similar thing happen, too. I remember they were like, "What is with you? Why do you do this kind of stuff?" I go, "I swear, I'm not doing it intentionally. I promise."

My mom, God bless her heart, she's not a helicopter mom, I remember she was in the trailer away for the majority of it. She doesn't want to ever feel like she's getting in the way and she's never wanted to ever tell me how to do what I need to do. She's like, "You do your thing. I'll be here watching 'Gilligan's Island' in the trailer." My whole childhood was her watching "Gilligan's Island" in the trailer while she was painting, but she is constantly worried about my physical safety, so heads would've rolled if it would've been a worse thing. If there would've been blood, heads would've rolled, for sure. It would've been a genuine horror film on that set.

Despite that little accident, young Nathan Gamble and Thomas Jane had a bond on set, something that is crucial for the audience to buy, or else the brutal ending loses its impact.

Jane: They talk about chemistry between actors, either have it or you don't, and sometimes you gotta fake it. I don't think it can be truly faked, but me and Nathan just kind of hit it off. He was a good kid, we enjoyed each other's company. He wasn't an annoying kid. He was very open and very curious, very unpretentious, not a child actor guy at all. His dad was really laid back and cool. And we had a good relationship. It just came naturally.

Gamble: It's so funny because I think a lot of people see [Thomas Jane] as this serious guy. He takes his job very seriously and rightfully so. He's a respectful person, he's a professional. I tossed the ball with him between takes, I remember that. I remember him talking about eating crawfish with me a lot. And I remember him just laughing with me.

Like I said, as a nine-year-old, I don't know how much of what I retained is necessarily 100% and conclusive, but I just remember that those big takeaways is that he wasn't really like a father figure. He was more just like a fun, big brother in a sense. He wasn't like, "All right, now I'm going to tell you a life lesson on how to act." It was more of just like, "Hey, look at that, isn't that funny?" Or just goofing off and tossing a baseball. We tossed the baseball a lot.

I haven't really spoken to him much since, and I just remember that he was like the big brother on set to me.

One of the most important moments in the movie is a quiet scene between David Drayton and his son, where the boy makes his father promise not to let the monsters get him.

Jane: That's the key moment in the script and in the story. We duly paid attention to that scene and took the time to get exactly what Frank wanted out of it. [Billy]'s speaking for himself, but he's also speaking for all the characters, from the crazy lady who starts her cult to everybody in the movie is basically saying "don't let the monsters get me."

I mean, if you wanted to break it down, that's part of what the story's about. What are the decisions we make based on fear versus the decisions we make based on love? Those are kind of the two main drivers of the human condition.

A quick trip to the pharmacy

Another stand-out scene is when David Drayton leads a small group on a journey to the neighboring King's Pharmacy. They encounter some truly nightmarish spiders in this space, which presented cinematographer Rohn Schmidt with some unique lighting challenges.

Schmidt: One of the hardest sequences that kept me up really from when I read the first script was the journey to the pharmacy, which is scripted as a day scene. It had lots of creatures jumping out at you. In a night scene, it'd be easy to create a little shadow that they'd pop out of, and here I was in this white cloud trying to hide creatures that could jump out and scare you. So that kept me up a lot.

I did a lot of testing. I think probably every day off I would go ask the effects people to smoke up the set and I'd take a still camera down and experiment with different combinations of fill light and flashlight and levels of smoke and finally got the recipe down for that, on how thick to make the smoke, which wasn't the thickest smoke and how much contrast to put into the final color correcting.

That was lit entirely with flashlights. By that time I had gained the trust of the cast where, in the midst of acting, they would be able to put the flashlight down, "I need you to put it here on this spot and aim it at that box there," but they were all in. They loved it. They were very accommodating to the plan there and it worked out really great. It's scary.

The pharmacy scene also hides a very geeky easter egg.

Witwer: "The Force Unleashed" was going to come out a year later or something like that. I think I'd shot "The Force Unleashed," and then went directly to "The Mist." I wasn't feeling particularly macho, so when someone gives me the knife, I hold the knife in the reverse grip because I wanted to subconsciously remind the audience that I can indeed beat up Darth Vader. Don't mess with me. It's my reverse lightsaber grip. I think that was my way of making myself feel better that I was a space tough guy.

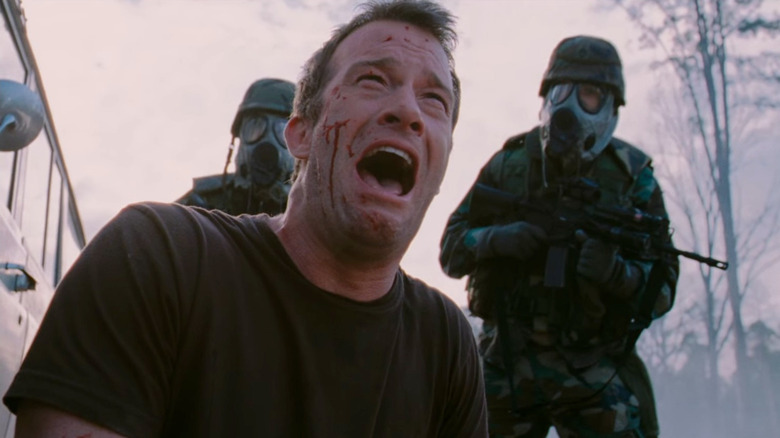

The murder of Private Jessup

The scariest scene in the movie, however, doesn't have any creatures in it. Throughout the story, the fanatical Mrs. Carmody gains more and more power as a cult leader of sorts. She and her followers believe they can stave off the monsters outside by performing human sacrifices, and their first target is Sam Witwer's Private Jessup.

Huth: I really think it's the scariest scene in the whole movie. This isn't the monsters, this is the people and people are always scarier than the worst monster you can imagine. When Mrs. Carmody has directed them at this person and said, "This is who we blame. This is the person whose fault it is." All of the rage and all of the terror, because it all comes from fear, is released onto this one poor guy who really had nothing to do with anything. Yes, he was in the military, probably didn't even know what was going on with these experiments, had nothing to do with it, but she's given them someone to blame.

And he goes from being sort of this tall, cute, handsome soldier guy to being a helpless individual who is at the mercy of people who have lost their minds, people who are so afraid that they will do anything, will do things they never would've imagined they could have done.

They stab this man repeatedly and then throw him out to the creatures. And in their minds, it's the right thing to do. In their minds, it's completely justifiable and that is the most terrifying thing in the entire movie.

Witwer: What's funny is when you're a young actor you have instincts, but you can't actually describe to people why you're doing it. And as a young actor, I remember I had this instinct of doing all these weird things with my hands when I had been stabbed and when I was carried out of the grocery store.

And only now do I realize, if you watch newborn babies, their hands contort in ways that, if you've had hands for a while, you don't use your hands like that. But babies use their hands in strange ways. And I was doing that. I was, on some subconscious level, acting like [Jessup]'s being born into the real world essentially. We're going out of the womb of a fun Hollywood movie into the real world of people who can be awful. And he's being birthed into the world of the mist. So, my hands, if you watch when I'm being carried out, I'm doing baby hands. I'm doing baby fingers.

I felt like having any kind of aggressive reaction [...] was wrong. Do you know what I mean?

I think that when faced with certain horrors, I think we all regress. That was definitely my instinct. The character's body language throughout the movie is not very aggressive and the least so when he starts getting murdered by the mob.

Schmidt: It's kind of a passion of the cross there. I think he even has his arms out or they're holding his arms out. And that was very much on purpose.

What a great place to do that in. It's like going through an ancient narrow cobblestone street as they wind the way through the aisles of the supermarket there. It was hard to get high enough (to capture that shot). It seems like it's a big tall roof, but I think the first couple takes we kept trying to get wider and wider because it was so powerful and dramatic.

Even though we had our widest lens on we ended up knocking some of the lights off of the ceiling with the crane, raining them down onto the extras down below. We had to stop and get out a bunch of big ladders to take down those lights just so that we didn't injure somebody.

Everybody brought it to that scene. Frank whipped them up into a frenzy and it was a little terrifying. You just looked at each other and went, "Okay, this is a little creepy and scary," just a little too real sometimes.

We had a fantastic set of recurring extras. It was the same people. It wasn't just random people showing up each day, so we had gotten to know them. We'd been in there for weeks on end, all day every day in the supermarket, and then to see them just become so sinister as a group was creepy. You hope you're capturing that. You hope that your camera is in the right place because you've now created a situation, a scenario where you can get and really communicate that terror there.

A key contribution to the script

Jessup's murder was not only a big scene for Witwer to perform, but it also marks a moment where he had a big impact on the actual script.

Witwer: I want to point out before I say this that I was coming up with a lot of harebrained ideas that really had no value whatsoever.

Frank was so patient with me as he would hear me pitch something and be like, "Yeah. Okay. Well, we're not going to do that." But he was such a cool guy. I mean, I really shouldn't have been pitching out all those stupid ideas, but he, at the very least, acted like he wanted to hear what I had to say or at the very most, genuinely wanted to hear what I had to say.

Anyway, so one day, like a clueless, young, stupid actor, I walk out and he's having a break. He's taking five minutes to himself outside because this guy is literally under siege. Directors are under siege every moment of every day. So, there he was taking five minutes to himself and I walked up to him. "Hey, Frank. Can I ask you a question?" And he snapped out of whatever private indulgence of having a moment of rest he was having and said, "Yeah, sure thing. What's on your mind?," which is an incredibly kind thing that he just took it with a smile, right?

And so, I said to him, "Listen, tomorrow or the next day, we're going to shoot my death. Norm, the bag boy got killed in a wonderfully grotesque way and we've had flying birds and people burning, and all kinds of just spiders and all kinds of crazy stuff. We've had our fun horror film. I think what we need when I get killed is a murder. A very personal, unpleasant murder."

And he is like, "Okay. Where are you going with this?" And I said, "Well, in the script, it says that I get stabbed and all that stuff happens. "Expiation!" I get thrown out into the mist and then I go back to the window. I'm bleeding and I start screaming, "Let me in. Let me in." And then, when I hear something, I turn around and I see that creature."

The script says I get yanked into the creature and blood and gore and body parts get sprayed across the whole window of the front of the grocery store.