The Mist Was Supposed To Contain More Practical Effects, But Time Wasn't On The Movie's Side [Exclusive]

Frank Darabont may have made his name on adaptations of Stephen King's more sentimental works "The Shawshank Redemption" and "The Green Mile," but for my money, his greatest triumph with King's oeuvre came with the down-and-dirty, depressing monster movie "The Mist" in 2007. The one-location potboiler harkens back to the frenzied allegorical creature features of decades past for a taught, tense time at the movies. In /Film's oral history of the film, Darabont said of creating it, "I just pictured one of those low-budget movies that we grew up all watching. In my case, pre-video, late at night usually on some creature feature," and on that level, he basically succeeded.

However, the major difference between "The Mist" and the films it's inspired by is the advancement of digital effects. The turn of the 21st Century saw the regression of practical effects and more of a reliance on animators and computer effects artists to create creatures, monsters, and all the other things usually done by sculptors, technicians, and makeup artists before. Oftentimes, these digital effects were implemented before the technology was even passable. The classic practical effects of the creature features Darabont loved also date those pictures, but because of the handmade qualities of those effects, there's still a visceral immediacy to them. He had hoped to make the film like those older pictures, utilizing as much practical effect work as possible.

Unfortunately, the process by which movies get made today has changed dramatically since the earlier days of cinema, most notably in pre-production and shooting. Therefore, the effects that he wanted to use may be practical for dramatic purposes, but they weren't practical for logistical ones. So, they had to shift their approach over to digital effects for some of the film's biggest sequences.

The crunch of production

By design and circumstance, "The Mist" was made quickly and cheaply. Frank Darabont reveals in the oral history that he "had $18 million to shoot and about, gosh, what was it? 34 days to shoot." For a movie with a lot of intricate effects work, that is such a short window, and if you are building things for in-camera, that will cost you more money upfront. They were able to build some things for real. Co-producer Denise Huth said of the creatures:

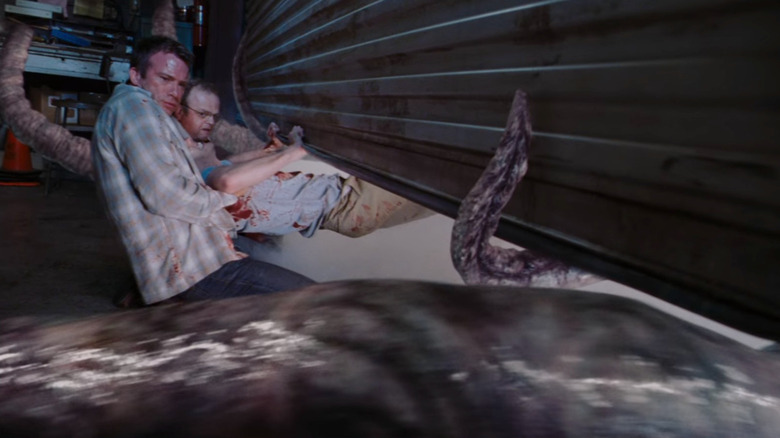

"Greg [Nicotero] and his team at KNB EFX designed so much of the creature work and actually built models of a lot of it; of the tentacles, of the bugs, certainly the spiders. There were a lot of the creatures that they had, practical things built to scale for us, which we could use in some shots."

However, the giant tentacles and flying bugs were just a little too difficult to maneuver on a tight schedule. Having a swarm of bugs flying around and attacking people requires extensive rehearsal to get right, as does having a puppeteered tentacle wrap around people. In 34 days, you don't have that luxury. Huth continued:

"We didn't have the time that practical effects always take. Everybody prefers seeing something real as opposed to something digital ... But we don't live in a perfect world, we live in a filmmaker world and you gotta make it work."

As a result, these sequences feature extensive use of CGI. Unfortunately, I find this to be the film's one major downside, as the threat of what's in the titular mist never feels as real as it should. They're a compromise, but the movie still works despite them. Although, I do believe the black-and-white version of "The Mist" helps disguise their artificiality.