Casting John Wayne Led To Some Strict Rules On The Set Of True Grit

Henry Hathaway's "True Grit" went before cameras at a particularly fraught moment in United States history. Richard Nixon had been elected President by campaigning on a racially tinged "law and order" platform. The Vietnam War was still raging despite 39% approval from the American public, sparking massive protests in cities and on college campuses all over the country. This unrest was reflected in the pop culture of the period, particularly in film. The nation's youth were inspired by the maverick works of Dennis Hopper ("Easy Rider"), Robert Downey Sr. ("Putney Swope"), and George A. Romero ("Night of the Living Dead). They craved edginess and experimentation, and rejected the stodgy conservatism of John Wayne.

Hathaway was well aware of this contentious climate when he began shooting the slightly out-of-character Wayne Western. The 71-year-old filmmaker had worked with The Duke many times throughout his career, and didn't want anyone to rile his cantankerous star. This meant laying down a strict, amusingly particular set of rules in order to keep the peace.

The forbidden topics of politics and cattle

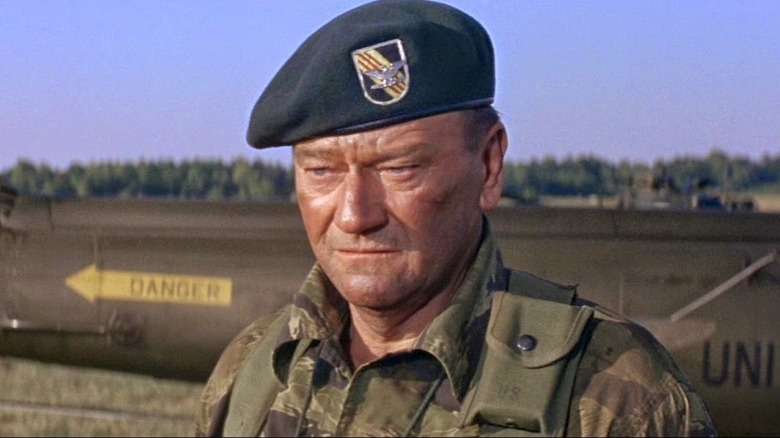

According to Scott Eyman's biography "John Wayne: The Life and Legend,", Hathaway's first rule held there would be absolutely no discussion of politics on the set. Though most people opposed the Vietnam War, Wayne was a fervent supporter of the conflict, as evidenced by his jingoistic 1968 film "The Green Berets." The movie was a commercial success, but had been downright shredded by critics. Wayne was attempting to repair his reputation with "True Grit," so the last thing he needed to hear was someone suggesting that his previous movie had been a laughable waste of time.

Secondly, there would be no talk of cattle. Yes, cattle. Wayne operated a ranch stocked with Hereford cows, and believed every other breed to be inferior. This rule was shattered early in the production when a brash Texas crewmember asserted that longhorns were superior to Herefords. Rather than attempt to mediate the dispute, Hathway quickly fired the Lone Star quibbler.

Hathaway as peacekeeper and taskmaster

Though Wayne had the run of the set, Hathaway was far from a pushover. He was also a bit of an eccentric. He abhorred plastic cups due to their tendency to get blown by wind into a shot, so, as with the Hereford situation, anyone who dared to brandish the disposable drinkware would be sent packing.

In "John Wayne: The Life and Legend," Hathaway explained his ruling philosophy thusly:

"'You have to have discipline,'" Hathaway asserted near the end of his life in explaining his theory of running a set. 'It's like a father with a big family. What do you do if a kid gets out of line? You've got to whip him or pretty soon all the kids are wild. Well, making a picture involves a mighty big family, and there's a lot of money involved, so I don't let things get very far out of line.'"

This likely didn't apply to Wayne, but, despite his penchant to bend the elbow, the veteran movie star wasn't one to make trouble on set. In any event, Hathaway worked swiftly and professionally, delivering a very good Western that restored Wayne's critical reputation and, most importantly, earned him his first and only Academy Award for Best Actor at the 1970 Academy Awards, which were held one month before the Kent State massacre tore the country apart. This tragic event probably didn't come up much on the set of Wayne's subsequent Western, "Big Jake."