How Straight Time And The Jericho Mile Influenced Michael Mann's Approach To Heat

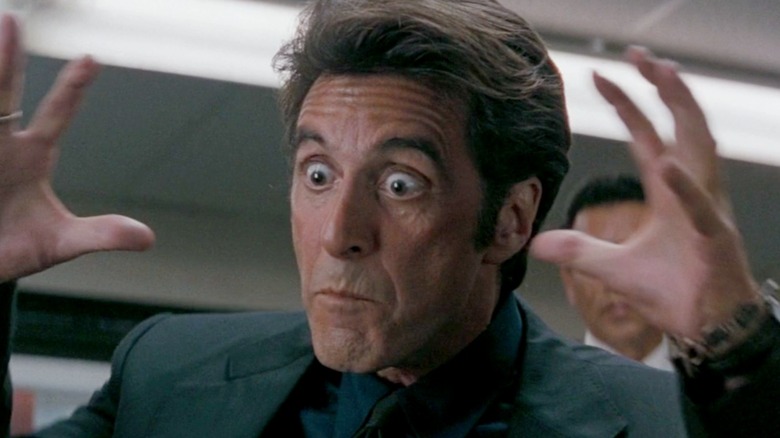

There's a reason "Heat" occupies such a unique space in the crime thriller genre — and it's not just Al Pacino's deafening delivery of the line "great ass". Influencing everything from Christopher Nolan's "The Dark Knight" to the virtual remake that was 2018's "Den of Thieves," the movie is a crime movie touchstone. Pitting career thief Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro) against detective Vincent Hanna (Pacino), the film also had the distinction of bringing together the two celebrated actors for the first time. But between the marquee names, epic action sequences, and inexplicably irate line readings, there's a nuanced and insightful touch to "Heat," which is exactly how director Michael Mann planned it.

Upon the film's release, critics such as Roger Ebert praised Mann's "uncommonly literate screenplay" and the "eloquent, insightful" characters that weren't "trapped with clichés." The director always had a knack for helping his audience empathize with disreputable types, even way back in 1978 when he took a pass at the script for Ulu Grosbard's "Straight Time." The neo-noir, based on a semi-autobiographical novel by master criminal Edward Bunker, contains the kind of bank heists and LA locales would become standard Mann fare.

But it was the detail in the script which would become the most quietly potent feature of forthcoming Mann projects. As early as his 1979 TV movie "The Jericho Mile," shot on location at Folsom Prison, the director would infuse his slick style with insights about his unsavory characters that went beyond moralizing or stereotyping. In 1995 the director had perfected this unique style, creating what is arguably its finest expression with "Heat". But it seems without "Straight Time" and "The Jericho Mile," the film may well have been more of an empty vehicle for De Niro and Pacino.

The 'astute' criminals of Heat came from real-life experience

As it turns out, Mann — who considers Heat a drama rather than a genre film — spent time in one of the country's first maximum-security prisons when researching "Straight Time" and filming "The Jericho Mile". Speaking to Vulture in 2017, he recounted his time at Folsom State Prison and how it had given him a sense of how a "mature prison population" functioned. Due to the facility being the "end of the line" for prisoners, Mann talks about how much of what he witnessed was a more ordered prison culture than he expected, which caused many of the inmates to spend time working on "their minds."

"Some convicts you encounter are stunningly literate. But, they're literate not because they took undergraduate philosophy. They had personal, practical, fundamental questions that they wanted answered, like: 'How should I view my life in time? What's property?' They'll read Kierkegaard, and Sartre and Marx and Engels. You encounter it with people that have sixth grade educations, who become quite astute in this raw kind of way."

It's this self-discipline which created the strangely erudite and worldly criminals that would populate Mann's movies going forward. In the case of De Niro's McCauley, it seems the director took direct inspiration from his experience working on "Straight Time" and "The Jericho Mile." As he goes on to tell Vulture, much like the "stunningly literate" inmates at Folsom, "men like McCauley, who have a strong ego and are disciplined, will ask themselves existential questions."

The uniquely nuanced magic of Heat

Do most people remember "Heat" for that thrilling shootout on the streets of LA? Or Pacino's now legendary manic line deliveries throughout? Maybe. But there's something beyond those striking moments that's allowed the film to endure as a modern classic. And it seems much of that is down to Mann mining his experience of meeting real-life criminals that don't conform to the cliché notion of what a criminal actually is.

The characters in "Heat" have dimension. McCauley struggles with his loner status, symbolized by his empty home, and what is clearly an addiction to the "juice" that comes from living the life of a master thief. Despite his degenerate activities he wears slick suits, epitomizing the kind of erudite criminal Mann witnessed at Folsom. Even Pacino's Hanna goes beyond the cookie-cutter maverick detective type. He struggles to connect with his stepdaughter and wife and ultimately, through his devotion to police work, finds something to connect with in McCauley's addiction to the criminal lifestyle. As Pacino told the Today show, "[Mann] saw them as part of the same coin but different. There was feeling there and respect."

Mann's statement that he's "not interested in archetypes" rings true throughout "Heat" and has clear roots in the director's experiences working on "Straight Time" and "The Jericho Mile." Sure, the film uses archetypes in the form of a cat-and-mouse, cops and robbers structure. But it's interested only in subverting those archetypes. Mainly, it seems, because as Mann's prior experience has shown, archetype all too often leads to stereotype. As it stands, the director did away with both to create something so remarkable that, no matter how loud Al Pacino yells, it remains a uniquely nuanced entry in the crime thriller pantheon.