Ad Astra's Moon Rover Chase Called For Some Serious VFX Tech

James Gray's 2019 film "Ad Astra" might be best described as "Apocalypse Now" in space. In the film, Col. Kurtz is replaced by the protagonist's long-absent father, and the remote jungle of Cambodia is replaced by the orbit of Neptune. Brad Pitt plays Roy McBride, a laconic astronaut with daddy issues who is assigned to investigate the source of fast-moving cosmic waves that threaten all life in the solar system. The waves, he knows, are part of an experiment that his father (Tommy Lee Jones) began working on some 16 years prior, leaving him behind on Earth. It is the late 21st century, and humans have colonized the moon and other worlds as well. The further one gets away from Earth, however, the more terrifying and difficult living in space becomes.

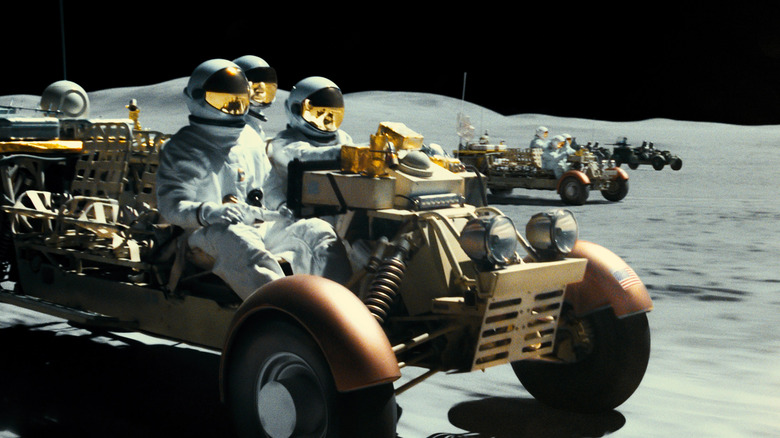

In the world of "Ad Astra," the dark side of the moon is contested property, and astronaut militia groups fight each other over the land. In one of the film's best sequences, Roy and his crew, while trekking across the moon's surface in a rover, are attacked by a rival rover that crashes into them and fires weapons. The sequence is filmed with muted sound in an approximation of what a space battle would actually be like. There isn't much sound in space. The lighting is stark and harsh, and Gray seems to have gone out of his way to make the sequence look as realistic as possible.

Hoyte van Hoytema, the cinematographer on "Ad Astra," had to come up with some creative lighting and camera techniques to shoot that scene. It was, as he discussed in a 2019 interview in Variety, actually shot in the Mojave Desert of California.

Fury Road on the moon

Although "Ad Astra" was not released in 3D, van Hoytema shot the film using a stereoscopic, two-lens 3D camera made by the now-defunct company 3ality Technica. One camera filmed ordinarily, and the other filmed in infrared. The infrared camera could more naturally alter the colors of the California landscape into something more recognizably lunar. In his words, the infrared "brings in pure black skies and very bright overexposed highlights that turn the desert ground into a white and high-contrast look that's similar to the moon." There were no green screens for shots in that sequence, only clever, high-contrast color manipulation. In post-production, the "normal" and infrared shots would be blended by the VFX team, and a few digitally enhanced "widening" shots would be added to make the landscape artificially extend past what they were able to film.

One could swear they shot on the moon's surface.

Another notable sequence in "Ad Astra" takes place on the surface of Mars, and the filmmakers sought the same level of visual authenticity for the Red Planet as they did for the moon. Thanks to photography taken by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, van Hoytema had the colors and the look of Mars on file and had to find a way to match the planet's magenta-hued sky. Additionally, the filmmakers studied a lot of NASA rocket launch footage to recreate the angles that the organization uses to film their own rocket flights. In recreating them, "Ad Astra" takes on a documentarian twinge, making the rockets seems that much more authentic.

Neptune is very far away

According to "Ad Astra," it takes only 79 days to travel to Neptune. Neptune, to remind the reader of their fifth-grade astronomy lessons, is about 2.7 billion miles from Earth when the two planets are closest. Light, which travels at 670 million miles per hour, takes eight minutes to make its way from the sun to the Earth. To make it from Earth to Neptune in a mere 79 days, a spacecraft would have to fly about 1.4 million miles per hour. The propulsion system that can carry humans at such enormous speeds is not directly addressed in "Ad Astra," so that part of the film's authenticity is a little bit fudged. Or, perhaps more pertinently, it's really not important to the story.

For the scenes where Roy McBride makes it to Neptune, however, the filmmakers were once again eager to measure out everything as accurately as possible. They studied the side and the rings of Neptune, trying to match the actual "real-time" on screen with the time it would take a real-life astronaut to travel between two points using modern tech. "Ad Astra" is a sci-fi film, but its space technology may be some of the more authentic seen on screen.

"Ad Astra" is ultimately very downbeat, with Roy McBride spending a great deal of time brooding and looking at the stars, into his own navel, and not really saying or doing anything of significance — in short, it's a James Gray film — but the visuals are some of the best one might encounter in a film of its genre. It's rare that a film looks like it popped in from the future, and "Ad Astra" certainly possesses that vibe.