Jazz Fest: A New Orleans Story Review: Riding The Line Between Celebration And Commercialization

We live in a seemingly never-ending age of music documentaries. In the last decade, everyone from Billie Eilish to Linda Ronstadt to A Band Called Death has had their story chronicled on film. This year alone has seen pictures about David Bowie, Jennifer Lopez, Kanye West, Sinéad O'Connor, Olivia Rodrigo, Dio, Sheryl Crow, XXXTentacion, Tanya Tucker, Nick Cave, and the New York City music scene of the early 2000s. I wouldn't be surprised if there are films I'm forgetting there. Frank Marshall and Ryan Suffern, the co-directors of "Jazz Fest: A New Orleans Story," have even made documentaries about The Bee Gees and the collaboration between Carole King and James Taylor, both of which have been released within the last two years. Music documentaries are inescapable.

What makes this overwhelming saturation even more depressing is how uninterested these films are at digging deep into their subjects. Most of the films simply come off as pure advertisements for the artists, as you will typically find the musician listed as one of the producers of the movie. They relay a paper-thin biography, interview other musicians about how great the subject is, sprinkle in a dash of controversy or troubled times, and include a healthy dose of performance numbers for the fans to bop along to.

"Jazz Fest: A New Orleans Story" doesn't follow one musical artist, but instead covers a signature American music festival. The New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival has been a staple of the city since 1970, when it was created by George Wein to give the birthplace of jazz its own Newport Jazz Festival. While the picture theoretically covers a festival and a city ripe for exploration as to all of the various sounds and people generated there, "Jazz Fest: A New Orleans Story" leans on tired tropes of music documentaries and gives us a surface-level ad for the festival. It's a somewhat effective ad, given the myriad of electric musical performances captured during the 50th year of the festival in 2019, but the film is utterly uncurious to examine the commercialization and commodification of a culture the festival was meant to showcase to the point where Katy Perry could be a headliner, performing a mashup of "Firework" and the classic gospel number "Oh Happy Day."

The joy of performance

Whether it's "Woodstock," "Monterey Pop," or last year's "Summer or Soul ( ... Or When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)," the main draw to any documentary like this is to showcase a variety of musical talents performing in an environment you are jealous you didn't attend. On this level, "Jazz Fest" sort of succeeds. When Earth, Wind & Fire break out their timeless disco classic "September," you can't help but smile and tap your toes along. Maybe you even do some lip-syncing. Why not?

But the even greater joy is watching the smaller acts and people you may have never even heard of before garnering similar-sized crowds that a group like Earth, Wind & Fire would get. That's part of the fun of attending a music festival. You could see jazz legend, Herbie Hancock, on one stage and walk over to see Nigerien assouf rocker Mdou Moctar on another. There's marching bands, gospel choirs, jazz quartets, and even a group playing in the middle of the carousel for the kids. "Jazz Fest" wisely gives a fair amount of time to these artists, many of whom are New Orleans locals, that give the film a much-needed spark when they do appear. A personal favorite was a performance from Tank and the Bangas, a group that blends together funk, hip-hop, spoken word, and rock all in one. They are creative, eclectic, and exciting, perfectly personifying the city they're from.

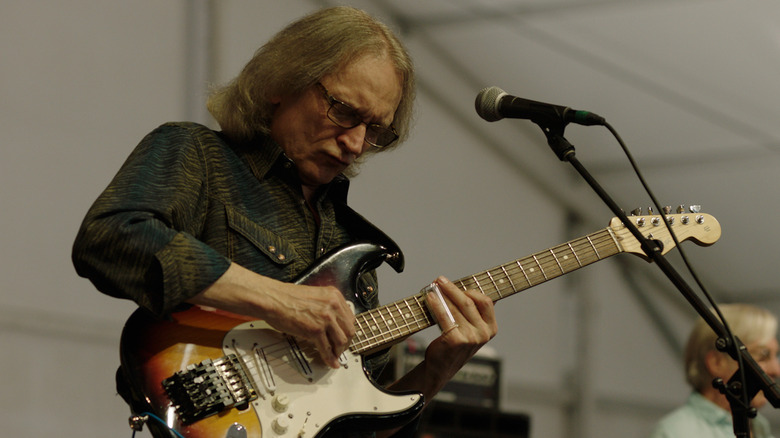

It's when the film turns its focus on the major acts that it loses its way, unplugging itself from the spirit of homegrown music the film preaches. Jimmy Buffett, who is also an executive producer on the film, has become a mainstay at New Orleans Jazz Fest, and festival producer Quint Davis frequently credits Buffett as the biggest driver of attendance for the festival, thanks to his loyal parrot head followers. Now, I've got nothing against Jimmy Buffett. As someone who grew up in Florida, his music was inescapable in my youth, and "Volcano" was an early favorite of mine. But this is not the man you want as the figurehead for a jazz festival. This event is meant to celebrate a predominately Black culture in a predominately Black city, and the indispensable one is the white guy in the tight-fitting, palm tree T-shirt singing about cheeseburgers? He also is the only artist who gets to perform more than one number during the film, including the finale.

And don't even get me started on Pitbull.

Music as a universal language

Outside of the performances and occasional bits of archival footage, this is a film overloaded with talking heads from dozens upon dozens of musicians. When they aren't telling you how great the food in New Orleans is (Note: do not watch this film when you are hungry because ... good lord, does the food make your mouth water), nearly every person talking to the camera here puts forth the idea of music as a universal language, and they repeat this sentiment over and over and over again. That is pretty difficult to argue against. A certain set of notes, chords, and melodies can transcend culture, race, language, age, gender, or other things that people identify with. Listening to music is a visceral experience, and you never know what will affect you.

What irks me about the message of "Jazz Fest" is that the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival should be a place for a community to celebrate its own culture, and that idea looks to have been increasingly segmented over its 50-year existence. You compare shots of the audiences from the early years of the fest to the ones shot in 2019 for the film, and the crowds become increasingly whiter, as do the groups on the main stages. I do not wish to knock all of those audience members who are clearly enjoying themselves, or the musicians performing their craft at the height of their abilities. I knock the documentary for not just brushing past this but ignoring it entirely. In the opening segment of the film, Jazz Fest founder George Wein explains that he was originally approached to start this festival in 1962 but was unable to because Jim Crow laws prevented Black and white musicians from performing together. There is no reflection on this matter. We just jump straight to 1970, when the festival begins.

The movie bills itself as "A New Orleans Story." While there are brief segments regarding the city's history, this is a film intended to celebrate just one thing, and that is the festival itself. It wants to be an uncomplicated space where people can come and have a good time for a week of music and food, but the history of people, culture, race, and art is anything but uncomplicated. When you are watching these people perform their music on stage with verve, conviction, and joy, it can be a beautiful thing. It's when they turn the camera away from the stages you find hollowness.

"Jazz Fest: A New Orleans Story" is now on Blu-ray and digital.