The Idea Behind The Good, The Bad And The Ugly Was Improvised On The Spot

When I saw "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" for the first time last year, I was taken aback by how it felt as if I had always known "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly." Blondie's forced march through the desert; Angel Eyes's back as he walks through a house full of dead bodies; Tuco running through the cemetery looking for the right grave marker. Not to mention Ennio Moricone's score, whose main theme I guarantee you can quote from memory even if you've never seen the movie. I cannot say if "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" is the best western ever made, because it has plenty of competition even among Leone's own work. But it makes as strong a case as any for mythic permanence, as if it was set down on a tablet rather than filmed.

Of course, "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" is not a religion; it is only a movie. Its production almost killed Eli Wallach, who played Tuco, multiple times. The crew had to blow up a bridge twice because they accidentally set off explosives the first time before filming began. Clint Eastwood was nervous enough about sharing the screen with two other actors that he fought Leone for as high a wage as he could get. "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" didn't start with a script, and it likely didn't even begin with Leone. At one point the working title was "Two Magnificent Tramps." But according to scriptwriter Luciano Vincenzoni, it began with three words improvised on the spot.

Three bums looking for money

Vincenzoni had previously worked with Leone on the script to "For a Few Dollars More." Leone's earlier "A Fistful of Dollars" had done very well. But according to Christopher Frayling's "Sergio Leone: Something to Do With Death," it was "For a Few Dollars More" that earned three times the box office record in Rome for a single film. Leone wanted to take his films abroad, and Vincenzoni knew English. They brought two representatives from United Artists to a "super-cinema" playing the film in Rome. Leone's work had not yet been discovered in the United States. But in Italy, he was a phenomenon.

According to Patrick McGilligan in "Clint: The Life and Legend," audiences were ecstatic to see "For a Few Dollars More." Past the turnstiles "was an orgy of laughing, screaming and yelling," says Vincenzoni. Once the film was over, United Artists were interested in more than just the rights to Leone's first two films. "What are you going to do next?" they asked. "Because we would like to cross-collateralize." It was Vincenzoni who thought of a poster reading "Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo," or "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly." He imagined a tale of "three bums that go around through the Civil War looking for money," but knew nothing more than that. Leone and his producer Alberto Grimaldi had even less to offer. But Vincenzoni's pitch was enough for United Artists, who offered a million dollars.

The anarchists are the truest characters

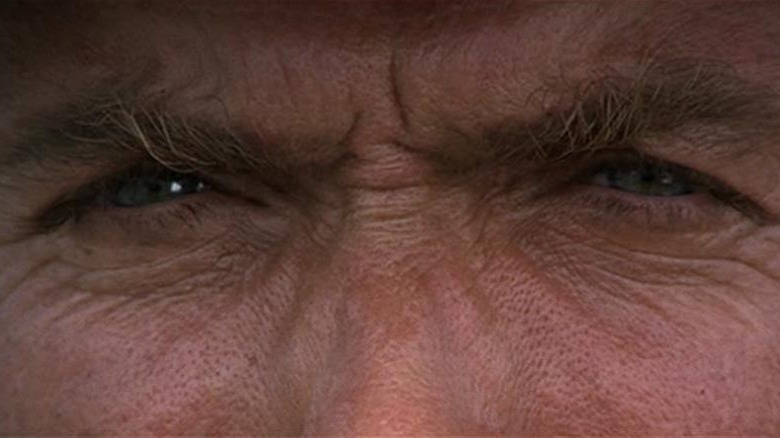

"The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" refers to Blondie (Clint Eastwood,) Angel Eyes (played by Lee Van Cleef) and Tuco (played by Eli Wallach), respectively. Their roles are announced by giant placards superimposed on the screen early in the film. But anybody who has seen "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" knows that the distinction between these characters is muddier than you might think. Blondie is the "hero" of the story, but is steely-faced and quick to violence. Angel Eyes briefly serves at what is effectively a Union concentration camp and leaves as soon as he decides his best interests lie elsewhere. Tuco suffers at Blondie's hands, but then he inflicts even worse abuse upon him at the first opportunity. All three are driven by money.

The world of "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" offers no room for typical movie heroism. Frayling quotes Leone as saying, "In my world, the anarchists are the truest characters." There's a reason why Tuco is the heart of the film, a fact that frustrated Eastwood to no end while reading an early draft of the script. Tuco's actor Eli Wallach embodies the contradictions of Leone's Wild West in ways that the archetypical Blondie and Angel Eyes cannot. But even Blondie and Angel Eyes surprise the viewer at times. "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" is mythic, but its gods are as capable of bad behavior as the fool.

That's their nature

Leone saw "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" as his most ambitious film to date, and carefully thought out its thematic underpinnings. "I have always thought that the 'good,' the 'bad' and the 'violent' do not exist in any absolute, essential sense," he is quoted as saying in Frayling's text. Just like that, Leone stakes his claim on the movie title Vincenzoni conjured under duress. Except that the title, and the deal, was Vincenzoni's idea. Reportedly, Leone was frustrated to no end by Vincenzoni's influence on the film, not to mention Vincenzoni's involvement in the "overseas sales" of "For a Few Dollars More." The tension between the two of them on the set of "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" would drive Vincenzoni to work independently for his next few projects, only to reunite with Leone for "Duck, You Sucker!"

Leone and Vincenzoni's relationship might best be summed up by their love of "Journey to the End of Night," a novel by cult author and antisemite Celine. The book is a deeply cynical picaresque in which its fast-talking protagonist travels the world and experiences the worst of humanity. The book is full of quotes like, "people cling to their rotten memories, to all their misfortunes, and you can't pry them loose...they're cowards deep down, and just. That's their nature." Leone has said on many occasions that "Journey to the Night" is his favorite book. But according to Frayling, Vincenzoni and fellow screenwriter Sergio Donati both swear Leone has never read a book in his life. It is Vincenzoni, Donati says, who could recite Celene from memory. Leone would listen, and then make movies. Good, bad, ugly.

Stupid and ugly

But all of that is besides the point. What is good, bad and ugly, Leone would say, but America itself? "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" is a civil war movie as well as a Western, one that depicts both sides as foolish. Whether or not the war was fought over slavery or a "lost cause" didn't matter, at least as far as Leone was concerned. "The Civil War...is useless, stupid; it does not involve a 'good cause,'" he would say. His hero Blondie blows up a bridge alongside a Union captain, but then lights the last cigar of a dying Confederate soldier. It's a vision of history well in keeping with "Journey to the End of Night," which similarly depicts war as "stupid and ugly." Rich coming from Celine, who stumped for the Nazis throughout his lifetime.

Historians may quibble with Leone's choices in creating the world of "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly." Leone borrows his Union-run prison camp in "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" from Andersonville, but switches its affiliation from one side of the war to another. He cited historical evidence that the Union army had prison camps, too. But Andersonville didn't belong to the North. We know today through works like James M. McPherson's "Battle Cry of Freedom" that the Civil War was fought over the economics of slavery, not mere stupidity. Then again, Leone always cared more for affect than accuracy. His war scenes feature weapons, such as a metallic-cartridge Gatling, that were not in fact used until after the Civil War. Their appearance is fitting in the great messy nightmare that is Leone and Vincenzoni's United States. Too beautiful for words, but encapsulated in just three, dreamed up at the last moment: good, bad, and...