What We Learned About Film History From The Venice Film Festival

Most giant film festivals are all about the present — and future — of cinema by their very nature. Audiences assemble to see premieres of the latest films that will come to define the upcoming months and discover new talent who will make their mark on the form. But given the collective cinephilia of the crowd, smart festivals also devote some of their programming to pay tribute to the rich archives of the medium that deserves recognition or rediscovery.

After two years dormant during the pandemic, the Venice Film Festival's classics sidebar came roaring back. The fest presented a plethora of new restorations that will no doubt trickle out through repertory cinemas and onto specialized physical media. But this section also included a handful of documentaries about cinema itself that took a critical lens to exploring the history and legacy of performers and projects alike. Here's what we took away after watching four informative, illuminating non-fiction projects.

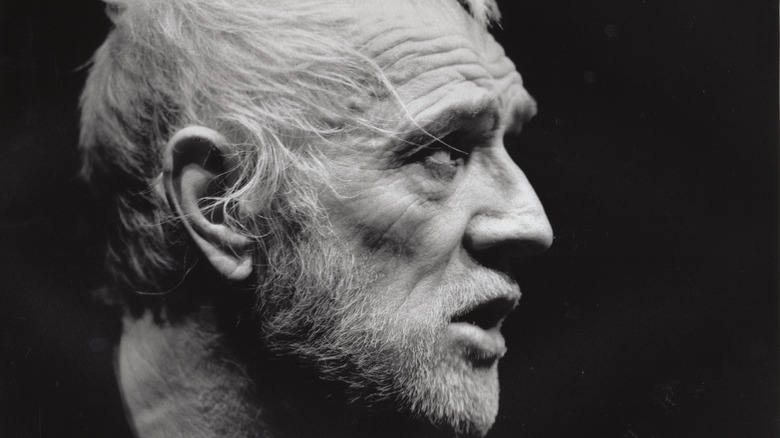

'The Ghost of Richard Harris'

"I'm going to tell you some lies about myself," quips Richard Harris at the outset of the documentary about his life and legacy. The actor, perhaps best known to contemporary audiences for his late-career turns in blockbusters like "Gladiator" and the first two "Harry Potter" films, certainly cut something of a chimerical profile. In addition to his thespian exploits on stage and screen, Harris was a singer, poet, rugby ruffian, and raucous drinker. (His children and grandchildren, including current working actor Jared Harris, would also have you know he was their patriarch.)

Yet Adrian Sibley's documentary "The Ghost of Richard Harris" would have you think it is in fact possible to nail him down. It spends over 100 minutes acting if the unknowable is in fact knowable, at least. Sibley isolates the spark of creativity and chaos that cut across all his work, identifying the alchemy he brought to film and theater alike.

The film is at its best when diving into how Harris was at the forefront of the United Kingdom's "Angry Young Men" with actors like Albert Finney and Richard Burton in creating "not art for art, but art from life." Sibley's talking heads attribute much of the volatility in his early roles to the chip on his shoulder from being Irish, a people the British innately regarded as working-class no matter what their station was. "The Ghost of Richard Harris" does veer off-course a bit in its back half as Harris himself becomes something of a roving troubadour. But even amidst the discursiveness, there's a real gem of a section analyzing his theatrical performance of "Henry IV" and how he destabilized audiences by daring them to believe he had simply gone mad. (The anecdote about how his granddaughter changed the course of cinema by convincing Harris to play Dumbledore instead of Gandalf is quite charming as well.)

But this documentary can never quite escape the feeling of a family album released to the public. For heaven's sake, the kids even rummage through his belongings in a storage crate! While there are some intriguing nuggets about craftsmanship and celebrity here, the appeal of "The Ghost of Richard Harris" may be limited to those with a pre-existing fondness for Harris. But for those folks, the doc might not tell them anything they don't already know.

/Film rating: 6 out of 10

'Bonnie'

Simon Wallon's documentary "Bonnie" is like a portal to alternate universes in cinema. The film's subject, legendary casting director Bonnie Timmerman, is perhaps the biggest power player in Hollywood over the last 40 years that people are not aware of. She's a cinematic gold panner, able to spot the faintest glint among the silt, and influential voice in the ear of directors. Her eye is sharp and her mind is a steel trap, recalling countless possibilities for casts that could have been. (Benicio del Toro instead of Patrick Swayze as Johnny in "Dirty Dancing" could have happened.)

Timmerman helped guide and shape the careers of many upstart actors, especially those toiling away humbly on New York stages and looking to make their mark on the silver screen. One memorable example cited in the documentary is how she could spot the potential in Brian Cox's commanding presence at The Public Theater, even though he performed most of the show with his back turned to the audience. She serves as their shaman through the audition process, helping to convince the actor – and the director – that someone is right for a part even when the previous work would not indicate they are a great fit. Without her, Sean Penn would have never branched out of his self-serious schtick and given the world such an iconic turn as Jeff Spicoli in "Fast Times at Ridgemont High."

Countless actors line up to tell their own story of working with her in "Bonnie," so much so that the documentary can feel like a pile-up of anecdotes and trivia. (The film's archives of audition tapes never cease to astound, though.) Timmerman's strength lies in helping actors getting over their nerves during the anxiety-inducing audition process, helping them connect with the inner light that she thinks can illuminate a role. Director Michael Mann also credits her with helping pioneer race-blind casting on the TV series "Miami Vice," giving countless actors their first big break and launching a diverse new generation of talent. But Wallon crafts something more comprehensive than just a coffee table book of movie miscellanea. It shows a casting director in action but also takes the time to explain what the unseen mover and shaker of the screen really does: mediate between director and script.

/Film rating: 7 out of 10

'Desperate Souls, Dark City and the Legend of Midnight Cowboy'

"No one ever really knows their own time," states a talking head in Nancy Buirski's "Desperate Souls, Dark City, and the Legend of 'Midnight Cowboy'." The documentary, however, makes the compelling case that John Schlesinger's Best Picture-winning film did. This is so much more than a glossy Criterion Collection extra, although it certainly does make a compelling case to reach for that edition to rewatch. Buirski situates "Midnight Cowboy" within the complex cultural and cinematic moment in which it was released in 1969, leaving contemporary viewers with a more nuanced understanding of what the film meant.

Schlesinger's film came two years after what most historians credit as the birth of the "New Hollywood," a group of upstart cinephiles and immigrant directors who supercharged the sagging studio picture with film literacy and foreign techniques. But Buirski makes a compelling case that "Midnight Cowboy" deserves recognition as importing the grit and grime that defined movements of Italian Neorealism post-World War II. America, spared from a land war on its own soil, was largely immune from the open hardship plaguing Europe mid-century. As cheery prosperity gave way to cynical disillusionment, Schlesinger captured the surface decay of New York City that mirrored a national malaise.

The decadence of Jon Voight's gigolo Joe Buck in "Midnight Cowboy" clashes with the destructiveness of the Vietnam War, which was reaching the nadir of its unpopularity at the time of filming following the Tet offensive. But through the character's naivete in the Big Apple as penned by screenwriter Waldo Salt, Schlesinger could explore countless issues ranging from the burgeoning movement for gay rights to the decline of Western mythology on screen. Buirski's film conveniently helps collapse the intellectual contradictions contained within the work while also capturing its sentimental core. While Voight's political leanings have complicated his persona in recent years, it's remarkable how powerful it is to watch him tearfully recounting just how much the film means.

/Film rating: 8 out of 10

'Sergio Leone: The Italian Who Invented America'

European cineastes love to claim they know American cinema better than Americans do, a frequent frustration encountered by any residents attending a festival overseas. But Francesco Zippel's documentary "Sergio Leone: The Italian Who Invented America" comes with a thesis – and receipts. He rounds up the big guns to explain what Leone meant to cinema at large as well as their own careers, making a compelling case for how the Italian maverick transformed the medium.

Zippel identifies the key paradox from Leone's personal experience that would animate his so-called "Spaghetti Westerns." The young movie lover grew up idolizing American cowboys under Mussolini's rule, seeing the country as representing freedom while his own home stood for fascism. But when the American soldiers came to liberate Italy in World War II, he observed little gallantry in their behavior. Having to square these observations led him to a skewed appreciation of the genre, loving the Western but not buying into their mythology.

As talking head Quentin Tarantino puts it, Leon was "trying to get to the bottom of genre archetypes" in his work. Zippel uses film historians and filmmakers alike to perform close reads of Leone's films, showcasing both their brilliance as well as how they kicked open the door for the so-called "Movie Brat" generation that emerged in his wake. Everyone from Steven Spielberg to Darren Aronofsky to Damien Chazelle – and, of course, Martin Scorsese – shows up to offer their own unique angle on what they took away from Leone's filmography. "Sergio Leone: The Italian Who Invented America" does get a little self-indulgent in documenting the director's final film, "Once Upon a Time in America," but even that's still an informative and richly observed section. Zippel's film is likely to become a mainstay in film studies courses about American cinema.

/Film rating: 7.5 out of 10