The Creator VFX Supervisors On How Being 'Good Cheaters' Helped Create The Film's Look [Exclusive Interview]

This post contains spoilers for "The Creator."

Visual effects are a necessary part of the filmmaking process when telling a sci-fi story about a human man who finds himself in a father-like relationship with an AI child while in the middle of a war between their two kinds. Gareth Edwards' "The Creator," however, uses VFX in a markedly different (and less expensive) way by having the folks at Industrial Light and Magic overlay their work in post-production after scenes were shot on location.

Edwards' approach required ILM to be more flexible in their work, both on set and afterwards. Edwards wanted so much flexibility, in fact, that he didn't even designate which of the extras were robots and which were human beings until post-production.

"He made it clear from the outset that he didn't want to be backed into a corner where now this person has got the mocap pajamas or markings all over them and then he's stuck with that extra being a robot," Andrew Roberts, ILM's on-set VFX supervisor, told me in an interview alongside the film's VFX supervisor, Jay Cooper.

I talked with Cooper and Roberts about the many ways "The Creator" was a different beast than their previous projects, including that intentional ambiguity of who would be AI and who would be human. Read on for our discussion, which touches on whether Edwards' VFX background was helpful or a hindrance, as well as some of the shortcuts they took to bring the movie's impressive visuals to the screen without a relatively huge budget.

Note: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

'I know you say you need this, but what happens if you don't really have it?'

Director Gareth Edwards has said that, to get the studio on board, he shot some footage and sent it to ILM, I assume to you, and you were able to do some visual effects without any of the traditional VFX equipment being used on the set, like the little silver balls and stuff like that. He just said of ILM that "somehow, they did it." My question to you is, how did you do that?

Cooper: We're really good cheaters. I've been working in visual effects for 25 years or so. There are best practices for making sure that you can emulate on-set lighting that have been developed over time. Traditionally, it's an HDRI and a LIDAR scan of your environment, and the balls that everybody loves. They are optimal but not necessarily essential. And over time, not every movie does that at a consistency you'd like, so you have fallback options.

So the question for Gareth really was, "Okay, let's assume that I don't do any of this. Is it even possible? What can we do? What can I get away with?" He wanted to kick the tires a little bit and say, "I know you say you need this, but what happens if you don't really have it?" So we showed him what it would look like if we didn't have it, and that was good enough for him and good enough for the studio, and then we were off to the races.

Now, that isn't to say that we didn't get those things, but we didn't get them in every circumstance, and it wasn't always exactly the right thing. But those two things together gave us, one, credibility and understanding that we'd be okay, and then two, that we could get better than nothing and maybe not everything, if that makes sense. And Andrew was there on a day-to-day basis to try to squeeze it out of Gareth as much as he could without slowing him down. I'm sure Andrew can speak to that as well.

Roberts: I think we benefited from Gareth having an understanding, a familiarity, and an appreciation for visual effects. So understanding that, okay, I really do need this, and then, okay, in this case I'm going to get out of the way. And this would be preferable if I had a blue screen and if I had all this information, but we know that at least with this minimal amount of information, I will be able to give Jay and the ILM team the data they need to be able to create a compelling shot. So a lot of it started from conversations in the morning before we would start shooting and going through the boards. We had a few storyboards for those key moments, and to really make sure the first day he was aware that, "No, that's fine. You go ahead for these shots. But no, I absolutely do need to shoot this high dynamic imagery so that I can reflect Alphie when she's in the barn or when they're out by the floating village and need to make sure that there are measurements for certain data."

So it was really that collaboration. It was that compromise to make sure that I got what I needed and that I was also there as a creative partner for Gareth to be able to answer questions.

There were times when maybe things didn't go as planned. So in the scene outside the barn when they're surrounded by police, they throw the grenade in and then a dog brings the grenade back out. That was planned to be a big stunt where they had a wire pole on a number of the stunt men that were going to be doubling for police. And they just couldn't get enough pressure where they just weren't flying up, or maybe one or two would and the others wouldn't, or it just wouldn't work at all.

Gareth's familiarity with visual effects was a good thing because we had that shorthand where he understood, "Okay, Andrew, your team will be able to animate that and give us what we need." Once I gave him the thumbs up, he was happy to move on and not worry, knowing that, "Okay, that shot's going to look as I need. I didn't get it in camera, but I am going to be able to deliver." There was that, making sure I captured the information, but then also be the reassurance for him that he would be able to get what he needed at the end of the day.

'He, obviously, has all the vocabulary to talk through these problems'

That actually leads into one of my questions: Was Gareth's background in VFX a plus or minus from your perspective?

Cooper: Can it be both?

Roberts: It was a plus on set. I would say that he understood what was needed, so I didn't have to convince him, "I need a blue screen in this situation." It was minimal blue screens, but there were a few circumstances where it was really important so that we could get a clean separation from someone's hair, perhaps, if it was a very low light situation. But then perhaps in post, Jay can talk to whether that was a blessing or a curse, but it definitely helped us having the same language on set.

Cooper: Gareth knows broadly what is achievable circa, gosh, I'm trying to think when he got off the box, probably it was probably pre-2000, honestly. But yeah, so he knows a lot — I'm not going to undersell his knowledge, because it's fantastic. And he, obviously, has all the vocabulary to talk through these problems. Some things are easier than he remembers, and some things are harder than he hopes, but that's true of every director. There's always a little bit of navigation there.

The thing that I think was the most helpful was when he would communicate, "No, no, no, I'm not asking for you to do something really expensive and hard. I want the cheap version of it." It's nice to have that shorthand. And certainly that's something that the movie benefited from. There are environments where we did fully CG environments with multiple week model builds and texture builds and all those sorts of things, and then there are ones that are really just little pieces of frozen artwork in the background that you can't tell, and we can get away with it because it's only a shot. We can have the conversation of, "You know that this will work for the shot, but if we have five more, it's not going to hold up." He's able to internalize that in a way that other directors who are maybe a little less knowledgeable aren't. So I think that helps in terms of our dynamic.

'We just had to figure it out afterwards'

One thing I'd love to talk to you both about is the two types of robots. There are the Sims with the human faces with some VFX on their ears and necks, and then the ones that have complete robot heads. I would love to hear about the logistics of creating those, both on set and in post.

Roberts: I had the easy part. On set, the basis for all of the robots were people, the extras on set. My preference would've been for Gareth to identify in advance that out of these 20 people, these five are going to be robots, so you can put your tracking markers on them and do all of the stuff that you would like to do. But he made it clear from the outset that he didn't want to be backed into a corner where now this person has got the mocap pajamas or markings all over them and then he's stuck with that extra being a robot. So instead, I took a lot of reference photography just to try and get a sense of the proportions of each person. But on set, Gareth just shot them. He wasn't saying, "You are a robot and you are a human." He just let them really lean into the performance of what was the emotion and what was the intent of that particular scene. And it was more of a post decision as to which ones would actually be turned into robots.

Oh, wow.

Cooper: Yeah. It's funny, because at a fundamental level, the most important part for all the robots and the simulants is that you actually interact with them where you feel like they're at the same sentience level as humans. So by coincidence or by luck or just kismet or whatever, the fact that they weren't heavily markered up or they weren't in motion capture pajamas or they weren't directed to be like, "You're going to be a robot," changes their performance in a way that makes them more human, which helps us in the storytelling, because they exist on that same plane of existence.

Then when it comes to the replacement, in the case of the robots, we're keeping the clothing, we're losing the bodies, we're painting out the heads, all those sorts of things. And because they're acting in ways that are human, because they are humans living in the real world, it helps their performance. I thought that was something that conspired to make more successful scenes.

Originally, for example, in the beginning when you meet Joshua [John David Washington] and Maya [Gemma Chan], and there's that one robot that's beating the heck out of Drew [Sturgill Simpson], that was originally a human performer that we replaced mid-show, where we really leaned into what the original performance was.

The same is true for simulants, where if you told them that they're half human/half robot or something like that, maybe there's a temptation that they'll act in some way that's a little otherworldly. But that was not the directive I think Gareth wanted in terms of what works for his story. So the more they can act like humans, the better. Then it's on us to figure out the rest. We have a suite of tools for locking down their head position. And we developed some tools to lock up the edges of their faces so we could integrate the mechanical components adjacent to them so that they don't slide against each other, so you don't get weird scissoring or anything.

What about the main cast, like Ken Watanabe's character?

Cooper: We always knew he was going to be a simulant, so we did the same thing. If you think about the way that Gareth wanted to shoot it, which is uninterrupted takes, being able to take advantage of as much time as he could with his actors, doesn't want to cut a lot, doesn't want to have the flow interrupted for someone to stick a ball in the middle of frame or anything like that. Because of this, we had very small tracking dots, like seven or so tracking dots on his head, and that was it. And we just had to figure it out afterwards. We did put all of our primary actors through a scanning session, so we had a geometry version of them, so we could use that to help us with things, and we'd render portions of their body if needed. But it was pretty low setup on the set side.

'We replaced a ton of stuff to make it feel like it was this otherworldly future environment'

I know that most of the film was shot on location — not all of it, but a lot of it. And your job was to paint over existing infrastructure in a lot of scenes. But I heard that for NOMAD, some of that was actually on location.

Cooper: Yes and no. There's no going to space. We did not go to space.

Fair enough.

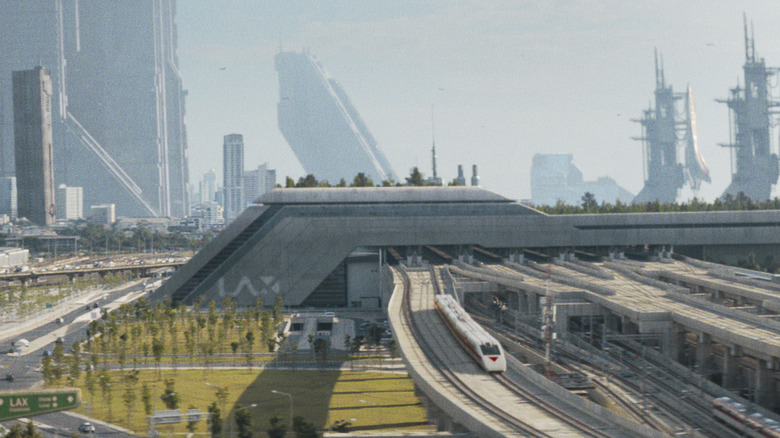

Cooper: There was no space jump with Joshua. But for interiors, what Gareth and Andrew smartly did was there were locations that we could use as part of the interior structure. So there was a shopping mall and a train station, and an airport interior that we could use as starting points. And I think it's something that we often don't think about, but I thought about it a lot during the production when I was traveling. If you're in the United terminal, what does that gantry space look like? What are the shapes of the walls? What is the polish of the floor? There's a lot of those sorts of things that we planted a flag in the ground of like, okay, these things are already established and we can build our world around that. It's going to feel that much more real because we have these surfaces and the structure to use as a starting point.

Can you talk a little bit about the process for making a location that's commonplace for us into something so sci-fi, for lack of a better word? It doesn't have to be NOMAD specifically, but what was the place that you feel like you transformed the most that might be most surprising for viewers?

Cooper: There's a bunch, but the floating village — there's all those massive forms around them, and the series of ductwork and all that kind of stuff. Alphie's lab, we're plussing up that environment. We shot at a particle accelerator where we're adding to those forms and making that a deeper environment. The checkpoint, where we have this really interesting structure around it. It's pretty much every single place that we went, James [Clyne, production designer] and Gareth and I, we would figure out what parts we could keep and what parts we would lose.

That usually meant, if I'm honest, we would basically circle the top half a frame and reinvent that. And we'd try to keep some of the lower structures and keep the parts that felt like they could tie in. But we replaced a ton of stuff to make it feel like it was this otherworldly future environment, but also keep the lighting cues and keep some of the texture and keep the ground planes and some of the other parts that help tie it in to make it feel like it's a built place and not something that's completely shot against blue screen.

"The Creator" is now in theaters.