Every Peter Weir Movie, Ranked Worst To Best

Some filmmakers are as well-known as their films. Think of the likes of Scorsese, Tarantino, and Spielberg — directors typically referred to solely by their last names. Others are every bit as beloved, even without the same kind of name recognition. Peter Weir is one such filmmaker, and while you won't hear casual film fans discussing "the best Weir," the odds are quite good that they love many of his films without even knowing his name.

Weir has made 13 feature films over his half-century career. (It should be noted that, while some people consider 1971's "Homesdale" to be his feature debut, its 50-minute running time means it's arguably too short.) Eight of them received Academy Award nominations with four of them taking home some gold. Some of Weir's films are better than others, but there's not a misfire in the bunch. Even the weakest among them is beautifully shot and filled with intriguing ideas and Weir's affection for humanity. That's great for Weir, but it's bad news for someone trying to rank his filmography. What kind of fool would even attempt such a thing?

Keep reading for my ranked look at the films of Peter Weir.

13. Green Card (1990)

Life in New York City isn't cheap, and Brontë's dream apartment is only open to married couples. Georges' troubles run even deeper as a Frenchman in the city whose visa is about to expire. Maybe a marriage of convenience is in order.

Ah, the romantic comedy. As ubiquitous a Hollywood genre as you'll find, but just because anyone can make one doesn't mean they should. Peter Weir chased the dramatically challenging highs of "Dead Poets Society" with an original script about a mismatched couple who meet, marry, and then fall in love. The concept is sound, but Weir's casting of Gérard Depardieu and Andie MacDowell put the brakes on both the romance and the comedy. The pair definitely seems like an odd couple, but the combination of Depardieu's aggressive oafishness and MacDowell's flat affect squashes anything resembling chemistry between them. To be sure, both talents have seen their particular charms shine elsewhere, but they struggle here. The wit and human touches in Weir's script are strong, though, and they're enough to balance out the underwhelming leads. High praise? No, but it's a passable enough entry in the rom-com genre.

12. The Way Back (2010)

It's 1941, and several men have just escaped from a Soviet gulag in Siberia. Life in the prison camp was difficult, but the path to freedom will challenge them like nothing else before.

Peter Weir's final film may not be his weakest, but like "Green Card," it feels, at times, like a stab at familiarity that somehow loses the director's voice along the way. The story is memorable, as Weir loosely adapts Slavomir Rawicz's memoir/novel "The Long Walk" (the author's claims of fact were later challenged) about an epic walk to freedom from Siberia to India. The film casts a capable Jim Sturgess in the lead role and surrounds him with a strong ensemble (Ed Harris, Colin Farrell, Mark Strong, Saoirse Ronan). As is often the case with Weir's films, the humanity of their situation quickly takes precedence over a need for historical truths. They face harsh weather, hungry wolves, dwindling food and water, and more threats along the way. The film suggests a great tale of survival, but it falls short, as it becomes an epic in search of more running time. At one point, they look up towards the Himalayas, their greatest challenge ahead of them, and then, Weir cuts to them pretty much wrapping it up. It's an odd choice that deflates the drama to some degree, but the affecting performances and inspiring journey remain.

11. The Cars That Ate Paris (1974)

Residents in the small rural community of Paris, Australia, have a peculiar way of keeping the town solvent. The key to their survival? A curious rash of car crashes that leave tourists dead or hospitalized and their belongings stripped, sold, and disposed of as if they were never even there.

It's not uncommon for a filmmaker's first feature to rank near the bottom of their filmography, and that holds true for Peter Weir's feature debut, "The Cars That Ate Paris," but it's nonetheless an engaging movie. It's a blend of genres with dark comedy and paranoia trading paint with terror and vehicular action, and it's only the lack of a stronger narrative and thematic grip that keeps it from greatness. Between the rural weirdos and metallic carnage, Australian genre tropes are plentiful, but Weir loses his way a bit by introducing a generational clash into the town's populace. That conflict is teased and leads to third-act destruction, but the film is otherwise focused on one stranger's attempt at understanding his indoctrination into the town's ways. Neither thread gets the attention or conclusion it deserves, but like all road trips, it's more about the journey than the destination.

10. The Mosquito Coast (1986)

An American inventor filled with mistrust and disgust for the American way devises a plan to save himself and his family. He packs them all up and heads to the jungles of Belize, but his hopes for utopia take a dark turn with him in charge.

In retrospect, maybe pairing a director like Peter Weir with a writer like Paul Schrader wasn't the best of ideas. Weir makes movies about people who are challenged, while Schrader prefers people who are damaged. There's a difference, one typically found in a thin layer of optimism running through the former's work, and it leaves 'The Mosquito Coast' feeling somewhat uneven. That unsettled feeling arguably works to the film's advantage in some ways, though. Much as casting "good guy" Harrison Ford for the role of the brilliant but belligerent patriarch does. Ford's performance as Allie Fox, one of his best, keeps viewers on edge, and the character's constant push and pull is equally engaging. There are bumps along the way, particularly with underserved supporting characters like Allie's wife and son (Helen Mirren, River Phoenix), but Ford is a powerhouse who's difficult to look away from. Watching Allie steamroll his way through both the jungle and his family's well-being shifts the film from drama to adventure to an American tragedy set thousands of miles away from home.

9. The Year of Living Dangerously (1982)

An Australian journalist named Guy Hamilton arrives in Indonesia to cover the country's ongoing unrest and soon finds himself in over his head. A coup is brewing, and no one can be trusted aside from a British woman who shares his bed and a local man who shares his heart.

Peter Weir's look at the violent turbulence of 1960s Indonesia won Linda Hunt an Academy Award for her audacious performance as Billy Kwan, a Chinese-Australian man. She's the heart of the film and is convincing as a man whose ideals ultimately put him in harm's way. Mel Gibson plays the journalist, and while his relationship with Sigourney Weaver's embassy employee gives the film some heat, it's his friendship with Hunt's Billy Kwan that grounds the film's themes. Hamilton sees himself as a moral champion bringing word of these poor people's plight to the "enlightened" West, but it's only through his time with Billy that he comes to see just how unimportant his journalistic ambitions are in their story. It's a small, personal connection amidst the bigger, violent landscape that makes the film so compelling. That humanity comes straight from Weir, and it's buttressed beautifully by Russell Boyd's lush cinematography and Maurice Jarre's atmospheric score.

8. The Last Wave (1977)

Four Aboriginal men in Sydney are arrested for murdering one of their own, and the solicitor assigned to defend them begins to suspect there's far more to the case. The lawyer soon finds himself plagued by strange encounters and apocalyptic visions.

Peter Weir's third and final horror-adjacent feature after "The Cars That Ate Paris" and "Picnic at Hanging Rock" is also a peculiarly Australian narrative. Like the latter film, "The Last Wave" is a story about the earth itself rebelling against those who don't belong, but the ambiguity is even stronger this time out. The legal angle clarifies the divide between the "newcomers" and the indigenous people, with a rule that native, tribal concerns have no sway as these are city Aboriginals. However, Richard Chamberlain's lawyer character is every bit the outsider, a city-dweller out of touch with nature, and the mystery unfolding before him forces a reckoning. It's a personal one, but the film suggests he's being made privy to something far bigger than himself, something he has no chance of preventing, and the result is a hauntingly atmospheric piece of eco-horror. The power of suggestion is key, though, both for the lawyer and the audience as pieces fall into place that spell either doom or coincidence. The film leaves the question unanswered. The lawyer believes, and if you're paying attention, you will too.

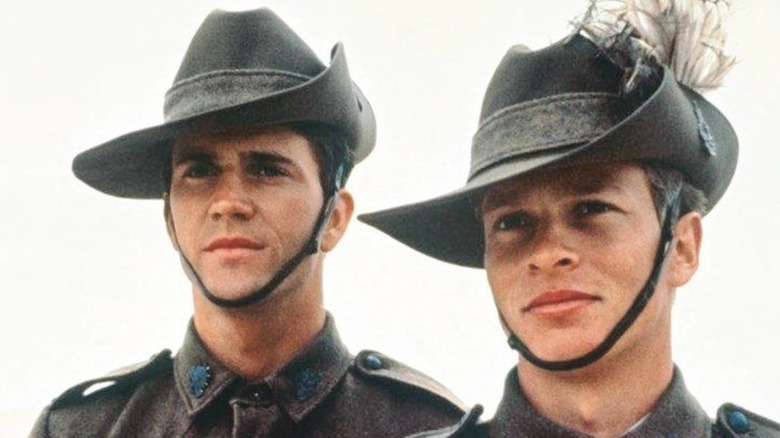

7. Gallipoli (1981)

Two young men meet during a track and field event and become fast friends, but the shadow of World War I looms large. They join the Australian forces and head to Turkey where they discover that honor and good intentions are meaningless once the bullets start flying.

War films come in a few different varieties, but a key theme running through many involves the collision between youthful courage and cold truths. Young people are emboldened by idealism and patriotism, only to be smashed against the rocks of reality. Peter Weir's historically informed film follows its fictional characters onto a battlefield that claimed nearly 400 Australian lives on August 7th, 1915, and that final freeze frame hits as hard as anything in Weir's filmography. Getting there, though, is every bit as engaging, as we follow the two young men through a burgeoning friendship, grueling training, and the rapid deterioration of their innocence. Mark Lee and Mel Gibson take the leads, and both do strong work, capturing the journey from enthusiasm to bravery to the battlefield. Weir catalogs the tragic unfairness of war from the callous decisions made by higher-ups safe from harm to the cruel fates awaiting others, and his condemnations are clear, but it's the personal story of these two friends that remains front and center until that final shot.

6. Dead Poets Society (1989)

A boys' prep school welcomes its new students in 1959 alongside the arrival of a new English teacher named John Keating. The rigid and stifling school is soon shaken by Keating's teaching methods, which encourage his students to find their voices in a sea of conformity.

The late Robin Williams gave audiences many unforgettable performances, including this one, which saw him receive a best actor Oscar nomination for his turn as Keating. He may be the film's driving force, but its beating heart belongs to the boys (Ethan Hawke, Robert Sean Leonard, Josh Charles, and others) who come alive under Keating's inspired and energetic teaching style. They grow in their appreciation for words, feelings, and the need we all have to be and show our true selves. It's not necessarily groundbreaking, but Peter Weir crafts an atmosphere of such strict and chilly obedience that the boys' attempts to shatter it become cheer-worthy accomplishments. The more cynical among today's filmgoers might scoff at the idea of teenage boys getting lost in poetry, but there's a real beauty in the idea that art can change your world. Add in a haunting score by Maurice Jarre and a tragic outcome for one character (one that floors you even though you see it coming well in advance), and the film becomes a good litmus test for weeding out the soulless among us.

5. Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003)

Captain Jack Aubrey commands a ship in the British fleet, and he's faced with a difficult choice after being ambushed by a superior French ship near South America. Skulk off for the safety of repairs, or chase it down and repay the favor? His choice will push his ship and its crew to their absolute limits.

For every "Pirates of the Caribbean" franchise, there are a dozen films that never got the sequels they deserved. This seafaring epic is one such film, as it not only ends on a tease for more to come but was also intended by 20th Century Fox's then-CEO Tom Rothman to kick off a franchise based on Patrick O'Brian's epic series of novels. It wasn't to be, but we still have this grand adventure that successfully pairs beautifully chaotic battle scenes true to the Napoleonic Wars period with insightful, humane time spent between shipmates. Weir shot both on the open sea and on a giant gimbal used previously for James Cameron's 'Titanic,' and we can't help but feel a part of the intensity of war. The quiet times are equally compelling, though, due in large part to the friendship between Russell Crowe's captain and the ship's doctor (played by Paul Bettany). They challenge each other just as the tides of both sea and war challenge them all, and the result is an intimate historical epic that deserved a sequel.

4. Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975)

It's Valentine's Day, 1900, and several girls from a private school are enjoying an afternoon out with a pair of teachers at a remote area known as Hanging Rock. The tranquility of the day ends abruptly when three students and a guardian go missing, and the mystery soon envelopes those who remain.

As with 'The Last Wave' above, Peter Weir's breakout film, "Picnic at Hanging Rock," is an atmospheric tale of horror and uncertainty. The film sets the stage well, with its remote locale and school girls pulling at the tethers of their societal restraints. You can feel that something is off. Watches stop, and as the trio of silent girls walks slowly off into the peak's crags and crevices, there's a pull to go with them — but Weir doesn't follow. Instead, we're left with a mystery, with proffered solutions both sexual and supernatural, and its repercussions claim more victims along the way. The lack of a tidy conclusion won't satisfy everyone, but viewers who thrive on suggestion, interpretation, and the haunting beauty of ambiguity will find a welcome embrace here. Weir and cinematographer Russell Boyd aid the film's dreamy feel by draping bridal veils over the lens at times to create a hazy look, and it succeeds in leaving audiences with one foot in the real world and the other someplace less comfortable.

3. Fearless (1993)

Max Klein is in a plane about to crash. He comforts those around him, and while many die, he and a few others survive. It leaves him a changed man. He feels invincible against all of life's dangers, but grief and guilt are strong adversaries.

An often neglected Peter Weir film, this adaptation of Rafael Yglesias' novel is a stunningly effective and affecting exploration of mortality. We don't meet Max before the accident, but it's clear he was a normal guy — a husband and father on a traditional path through life. The incident shakes him to such a degree, though, that his demeanor shifts radically. There's already an emotional undercurrent here, as Max becomes callous and flippant towards life (and death), but Weir and lead Jeff Bridges take the bold step to let Max become unlikable in his single-mindedness. It's a risky venture that threatens to lose audience sympathy, but the film's combined talents pull it off beautifully, thanks in part to the addition of Rosie Perez as a fellow survivor wracked with guilt because she was unable to save her infant child. It all sounds so introspective, but the film is a thrilling and gorgeous celebration of life. The film's finale reminds Max (and viewers) of the accident in its entirety, not just of his survival, and it's a sensory triumph elevated even further by the use of Henryk Górecki's Symphony No. 3.

2. Witness (1985)

A man is murdered in a bus station bathroom, and the only witness is a young Amish boy. The detective assigned to the case soon realizes that the prime suspect is a fellow police officer, and the boy's only hope is to take him back to his own community to keep him safe.

On its surface, "Witness" seems to be the most traditionally audience-friendly film of Peter Weir's career. It has good guys, bad guys, and a little romance to keep the blood flowing. And it is that, as evidenced by the film becoming a sleeper hit, but Weir's deft hand ensures it's also a film rich with emotion and insightful themes. The thrills and suspense are executed beautifully as bookends to the film's central focus, a tale of collision between cultures, between moralities, and between people. Harrison Ford's detective is a man prone to violence, something the Amish abhor, and his time among them before the bad guys come calling affords both time to learn about and appreciate each other. Conflict fades, admiration grows, and the possibility of romance blossoms with the boy's mother (Kelly McGillis). As with his films about Australia's Aboriginal population, Weir once again shows respect for the "other," the Amish people and their beliefs, through his lead character and his themes. It adds welcome thematic weight amid the action beats and ultimately gives more power to the final confrontation.

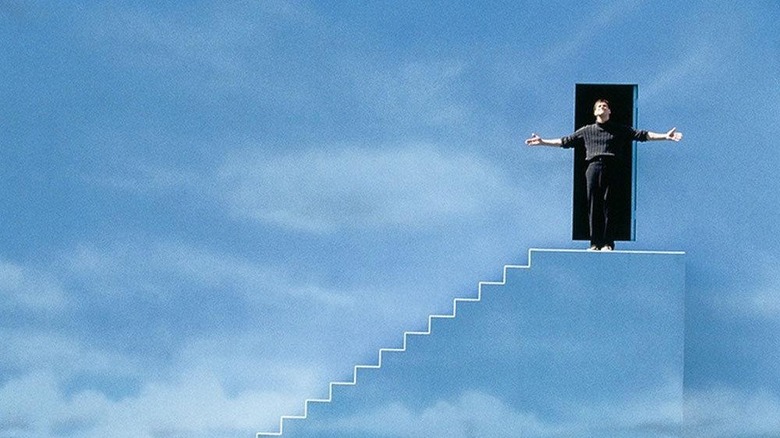

1. The Truman Show (1998)

Truman Burbank is a star — even if he doesn't know it. Chosen before he was even born, Truman is the star of an around-the-clock reality show that follows his entire life. The world is his audience, and everyone he knows is an actor. But what happens when Truman discovers the truth?

As difficult as some spots on this ranking were to wrangle, the best Peter Weir film was always going to be 'The Truman Show.' Jim Carrey soars as the naive but increasingly paranoid Truman, and big laughs and fun set-pieces follow. Once again, it's the pure heart that Peter Weir brings to so many of his films that lifts the movie from mere sci-fi comedy to a masterpiece about identity and the paths we choose for ourselves. Andrew Niccol's script is a smart, prescient look at the degree to which our lives are captured (reality television, social media, etc), but Weir's direction and Carrey's performance find the humanity behind the high-concept story. Truman's efforts to escape the show (the island he's on is essentially one big soundstage orchestrated by Ed Harris) increase in complexity and desperation, leading to a dramatic, emotionally charged finale that, even after multiple viewings, still brings the waterworks. Viewers cry tears of joy, relief, and hope for Truman's next steps, and perhaps more importantly, they're content letting him walk out the door and out of their lives because it's time he started his own.