The 12 Things You Need To Know About Quentin Tarantino's Filmmaking

Quentin Tarantino easily takes the title of the ultimate movie lover's filmmaker. Bursting onto the scene with "Reservoir Dogs" at the Sundance Film Festival in 1992, one thing was certain when his follow-up, "Pulp Fiction," came out two years later: this guy was cool. Tarantino displayed a fearlessness that movie buffs found refreshing. After all, the previous decade was filled with overstuffed franchises in the wake of Hollywood's New Wave movement at the end of the 1970s.

Known for his trademark over-the-top violence, nonlinear storytelling, and killer soundtracks, the major thing that sets the "Jackie Brown" filmmaker apart from his contemporaries is the sheer volume of homages to auteurs before him. As any die-hard Quentinphile will tell you, the writer-director was once a store clerk at Video Archives in Manhattan Beach, California, and was respected for his encyclopedic knowledge of virtually any movie. Tarantino is the reason why I began diving into movie history and old genre films, as his visual and thematic nods serve as phenomenal starting points for deep dives into cult, classic, and foreign cinema.

Since his debut, all of Tarantino's movies have an instantly recognizable quality to them — not to mention that his characters seem to live in a shared universe, complete with a slew of recurring fake brands you can spot in his films. Easter eggs aside, there's much more to dive into regarding this director's signature style. I've compiled a handy guide of crucial elements in Tarantino's filmmaking, and trust me, this is some serious gourmet s**t.

His movies are cinematic love letters

Have you ever watched a Quentin Tarantino film and wondered, "Haven't I seen this somewhere before?" Well, you probably have. Tarantino's movies are littered with countless pastiches and nods to classics, visually and sonically. When you watch Uma Thurman and John Travolta do a twist-off in "Pulp Fiction," the choreography borrows from Federico Fellini's surrealist comedy, "8 ½." Meanwhile, in "Jackie Brown," there's a scene with a neurotic percussion-infused score in which Samuel L. Jackson's Ordell realizes he's been hoodwinked by Pam Grier's titular character. If the music sounds familiar, it should because the Roy Ayers track "Escape" was also used in "Coffy," a 1973 blaxploitation flick starring Grier herself.

Tarantino's catalog consists of genre movies, and he does a darn good job keeping certain genres alive. In his 2022 book, "Cinema Speculation," I noticed that Tarantino offered some insight as to why he adheres to such strict thematic categories. Noting that directors before his time made genre movies because they were forced to by the studios that hired them, he explains that, in his case, he simply makes them because he adores genre films and is eager to let his obsessions shine through.

Whether you're a self-proclaimed film aficionado or just looking to get into some cult classics, his flicks serve as a cinematic gateway drug, and there's always room for another fix. I now consider Wong Kar-wai my favorite filmmaker thanks to Tarantino, whom I once heard wax lyrical about the Hong Kong-based auteur.

The three major shooting styles of Quentin Tarantino

When watching Quentin Tarantino's movies, you'll notice that he favors three specific shots — all used to convey different emotions without dialogue. The first is his striking wide shot (taken from his love of classic Spaghetti Westerns), which is most evident in "The Hateful Eight." These location shots are incredibly arresting, immediately informing the viewer of this harsh environment. While these wide shots look imposing, Tarantino believes they're quite personal. "It takes you inside the people, inside their space," he told Becker Films.

Next is the extreme close-up, which is a direct inspiration from Sergio Leone's Westerns. Unlike the wide shot, these close-ups draw attention to a specific detail — like Uma Thurman wiggling her big toe in "Kill Bill Vol. 1." A variation of this extreme close-up is the crash zoom, which adds a heightened air of anxiety. When the wicked Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio) is introduced in "Django Unchained," Tarantino uses this crash zoom, instantly letting us know that this is the most important guy in the room.

Lastly, we have the long tracking shot, which dramatically increases tension. I'll never forget the first time I saw "Pulp Fiction" and watched Bruce Willis' Butch sneak back into his motel room to retrieve his precious gold watch. A long, one-shot take follows as he pussyfoots toward the building. I knew that Butch shouldn't go back. After all, he's on the run from thugs — but Tarantino doesn't have to express that verbally. Instead, this long tracking shot made me riddled with anxiety.

What's in the trunk?

One less-obvious visual hallmark that Quentin Tarantino favors is the trunk shot, and once you pick up on it, you'll spot it in all his movies. From "Reservoir Dogs" to "Pulp Fiction" and even "Kill Bill," we'll catch characters popping the boot of a car, offering up a deliciously voyeuristic view of what's inside — or who's opening it up.

Why incorporate the trunk shot? It's used to convey a sense of the power of these characters peering inside. The dialogue is usually casual (these criminals do this regularly), while shooting from a low angle and looking up at our villainous protagonists also gives the viewer a sense of hopelessness. Of course, in his period pieces in which cars don't exist, such as "The Hateful Eight," we still see this extremely low angle, like when Samuel L. Jackson's Warren shoots Bob (Demian Bichir).

The first use of the trunk shot was in the 1948 film noir (a genre that Tarantino adores) "He Walked by Night." "The Killing," Stanley Kubrick's 1956 heist noir, heavily influenced Tarantino's debut, "Reservoir Dogs." However, the filmmaker has done much more with noir than include the classic trunk shot and his own take on the heist genre. In "Pulp Fiction," for example, Tarantino includes typical noir tropes, like introducing Vincent Vega (John Travolta) and Jules Winnfield (Jackson) as brooding criminals, his take on the noir MacGuffin with the enigmatic briefcase, and the iconic femme fatale: Uma Thurman's Mia Wallace.

Music plays a huge role in his filmmaking process

There's no doubt that Quentin Tarantino has some addicting soundtracks to accompany his movies. The "Django Unchained" director is known for the song selection in his films, which he uses as a tool to instantly set the tone or give us a deeper look into the mind of a specific character.

In "Pulp Fiction," viewers are immediately met with the assaulting surf guitar of Dick Dale's "Misirlou," declaring that this will be a no-holds-barred crime flick. Similarly, to this day, I cannot listen to what should be a jovial bop, "Stuck in The Middle With You" by Stealers Wheel, without thinking about the disconcerting ear-slicing scene in "Reservoir Dogs." The moment shows us just how deranged Michael Madsen's Mr. Blonde truly is, grooving along to the track while inflicting unimaginable acts of violence.

So essential are soundtracks to Tarantino that they make up the start of his writing process. In the booklet for his soundtrack compilation album, "The Tarantino Connection," he admitted, "One of the things I do when I am starting a movie ... I go through my record collection and just start playing songs, trying to find the personality of the movie, find the spirit of the movie" (via Far Out).

Spaghetti Westerns initially inspired him to become a filmmaker

It seems as if Quentin Tarantino entered this world with an unparalleled desire to become a filmmaker, but, of course, his feverish drive started somewhere. Speaking to Cinedome, the "Death Proof" director cites Spaghetti Western legend Sergio Leone as his first source of inspiration, noting the hyper-stylized nature of Leone's movies.

In countless Tarantino flicks, you'll catch nods to Leone. In the opening shot of "Kill Bill: Vol. 1," we see the Bride (Uma Thurman) lying helplessly in a chapel as Bill (David Carradine) shoots her in the head. This is a direct reference to "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" in which Eli Wallach's Tuco aims a gun at Clint Eastwood's mysterious character. In Tarantino's follow-up, "Kill Bill: Vol. 2," he makes things even more apparent, using "Il Tramonto," a score by frequent Leone collaborator Ennio Morricone, during one of the Bride's flashback sequences.

We can also spot this influence in less-obvious flicks such as the World War II-based "Inglourious Basterds." In a chat with Henry Cabot Beck (via "Quentin Tarantino: The Film Geek Files"), Tarantino dubbed it his "true Spaghetti Western-influenced film." Similarly to how Lee Van Cleef's Angel Eyes enters the home of Stevens (Antonio Casas) in "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" for an interrogation while they have soup, Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz) shares a glass of milk with Perrier LaPadite (Denis Ménochet) before a brutal and sudden shoot-out.

Quentin Tarantino's East Asian influence

Quentin Tarantino's movies often borrow elements from East Asian cinema, mainly from Hong Kong and Japan. The "Kill Bill" saga is an obvious example, with the Bride (Uma Thurman) wearing the same yellow tracksuit donned by Bruce Lee in 1978's "Game of Death." Even more so, the 1973 revenge exploitation flick "Lady Snowblood" was a tremendous influence on the story, with a young female assassin (Meiko Kaji) determined to avenge the deaths of her father and brother in a bloody hack 'n' slash escapade in the late 1800s.

However, "Kill Bill" wasn't the first time Tarantino drew inspiration from East Asian cinema. He made this evident with his feature debut, "Reservoir Dogs." Fans of John Woo's "City on Fire" immediately picked up on the familiar plot of an undercover cop forced to work with gangsters while another detective is completely unaware of his true intentions. Tarantino hasn't shied away from giving credit where it's due, even going as far as to dub Woo his "hero" in an early 1990s interview.

One lesser-known filmmaker I have Tarantino to thank for introducing me to is Seijun Suzuki, and in particular, his 1966 film, "Tokyo Drifter." This gloriously colorful, hyper-stylized yakuza romp was like nothing I'd ever seen before, yet I immediately spotted the similarities between it and "Kill Bill: Vol. 1." From the framing, which sees action sequences taking place in front of vibrant monochromatic walls to the meticulously choreographed fight scenes, Tarantino's 2003 hit is dripping with this Japanese B-movie's influence.

Blaxploitation films are a big reason he loves revenge cinema

Although Quentin Tarantino has mentioned being inspired by female-led revenge flicks from Hong Kong and Japan, he points to blaxploitation films from the 1970s as another significant reference for his love of revenge cinema. As he explains in "Cinema Speculation," he was exposed to this subgenre of exploitation movies as a curious nine-year-old through his mother's boyfriend, Reggie. Reggie was a blaxploitation savant and first took the boy to see "Black Gunn." Tarantino loved it so much that four years later, the teenager made an effort to regularly visit predominantly Black theaters and catch up on blaxploitation movies he missed when he was younger.

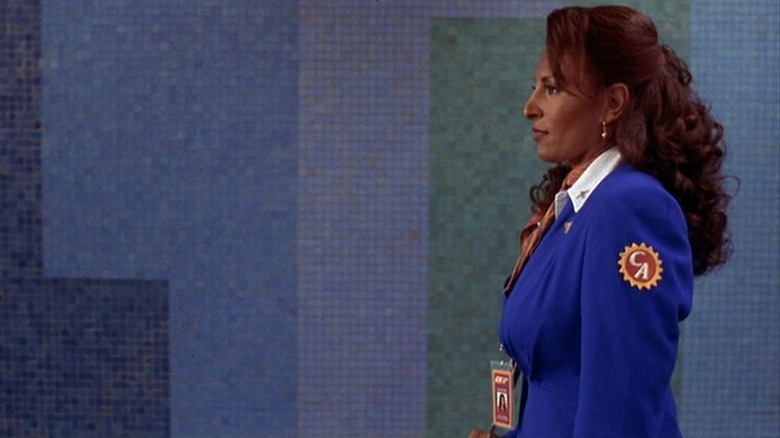

In a blaxploitation essay in "Quentin Tarantino: The Film Geek Files," Tarantino cites Jack Hill's "Coffy" as an inspirational source, dubbing it "one of the greatest revenge movies ever made." In 1997, he paid homage to this blaxploitation classic by casting "Coffy" star Pam Grier as his lead in "Jackie Brown," adapted from Elmore Leonard's "Rum Punch."

Tarantino and Reggie lost touch not long after their movie-going adventures, yet it's clear he impacted the now-celebrated filmmaker. At the end of the "Black Gunn" screening, Tarantino recalled a man sitting behind Reggie, who quipped, "Now that's a movie about a bad motherf***er!" Decades later, with the release of "Pulp Fiction," Tarantino still thought fondly of this moment, giving Samuel L. Jackson's Jules an amusing wallet that reads, "Bad Motherf***er."

His dialogue is drawn out with purpose

Quentin Tarantino's dialogue is unmistakable. A considerable part of his style is that his talk-heavy scenes are always drawn out like intricate, verbal dances between characters. "There is a bit of rhyme that happens between some of the words and some of the phrases ... it's not poetry, but it's not completely divorced from poetry," he once explained in a CNN interview.

The opening scene in "Reservoir Dogs" is over seven minutes long, focusing on a conversation in a diner. So why drag it out so much? Along with placing characters in a hyper-stylized situation, in this case, a group of criminals who are supposed to be talking about their next heist, he roots them in reality through mundane chatter. Tarantino also offers some vital subtext that primes us to understand these people better. We learn that Mr. Pink (Steve Buscemi) is a weaselly and contemptuous man. He doesn't even tip at restaurants, which sparks debate between his peers.

Later, after the film's climactic crescendo of violence, Mr. Pink hides and is, consequently, the last one left alive. Of course, this comes as no surprise. Mr. Pink has already complained that his pseudonym sounds like "Mr. P*ssy." And guess what? He lives up to the moniker. "Storytelling has become a lost art," the Academy Award-winning writer told Film Comment in 1994. "There is no storytelling, there's just situations." Tarantino's writing is effective because he indirectly tells us all we need to know.

Quentin Tarantino's movies will always be incredibly violent

Critics of Quentin Tarantino's work have often condemned the use of violence in his movies. They're not exaggerating. In his first eight feature films alone, the kill count sits at approximately 563. Pretty crazy, huh? As he told CNN, he uses violence to "wake up" his viewers and further a sense of community in the audience that he loves to experience himself.

While the Los Angeles-based filmmaker has no issue with cinematic gore galore, he's quick to mention that he doesn't condone it off-screen. With that in mind, when you watch Tarantino's movies, the violence is delivered in a cartoonish way that real-life brutality certainly is not. In "Pulp Fiction," when Samuel L. Jackson's Jules is driving a car with John Travolta's Vincent in the passenger seat, the latter turns around to ask their informant, Marvin, for an opinion. Suddenly, his gun goes off. "Aw, man, I shot Marvin in the face," Vincent laments. Travolta's delivery is impeccable, and you can't help but laugh at what should be a horrific scene.

Tarantino's unphased approach to violence is something he's had time to perfect. Even as a young boy, his mother allowed him to watch films that his peers would never be allowed to see. She was more afraid of him watching the news than fictional bloodbaths. "A movie's not gonna hurt you," the director recalls her saying in "Cinema Speculation."

Setting up for success with Reservoir Dogs

When Quentin Tarantino arrived on the scene with 1992's "Reservoir Dogs," he offered an invigorating perspective for cinephiles worldwide. On paper, the flick seems like a typical heist story, but Tarantino, being the ballsy newcomer he was, never actually shows a heist taking place. Rooted in characterization and focusing on a dark and humorous narrative, "Reservoir Dogs" revitalized the crime genre.

Of course, the now-cult classic is filled to the brim with nods to some of Tarantino's favorite directors and films, including Stanley Kubrick ("The Killing"), Akira Kurosawa ("Rashomon"), and John Huston ("The Asphalt Jungle"), to name a few. These tributes became staples in the years to come. However, out of all these legendary directors, the one that Tarantino recognized as being the most influential was French New Wave filmmaker Jean-Pierre Melville. The same year that "Reservoir Dogs" was released, Tarantino spoke to Becker Films and praised Melville's "Le Doulos" as his all-time favorite screenplay.

What Tarantino particularly adores about Melville was his ability to take typical genre tropes found in classic American gangster films of the 1930s and 1940s and reinvent them as his own — precisely what the "Pulp Fiction" director did for an entirely new generation.

Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood: Quentin Tarantino's 'magnum opus'

Quentin Tarantino has a lot of love for his ninth feature film, 2019's "Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood." Dubbing it his "magnum opus" in an interview with Esquire, he has a powerful connection to the period drama. It's set during 1969, a formative year for the filmmaker.

When you watch a Tarantino film, you'll see inspiration from 1960s French and Italian greats like Jean-Luc Godard (Tarantino even named his production company "A Band Apart Films" as a nod to Godard's 1964 drama, "Bande à part") and Federico Fellini. But what about American movies? As Tarantino writes in "Cinema Speculation," Hollywood's New Wave movement of the late 1960s shaped him (or as he puts it, "New Hollywood was Hollywood"). Filmmakers like Dennis Hopper and Robert Altman ushered in a fresh perspective far removed from the stuffy, whitewashed studio productions of the 1950s.

"Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood" is set after the end of Hollywood's golden age. Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) is the perfect representation of an Old Hollywood actor whose star is waning during this massive cultural shift, while the fictional version of Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) is an ethereal, fledgling movie star. With these two characters, Tarantino tells us what was going on in Tinseltown during this era. "[1969] is the year that formed me," he proclaimed to Esquire. "This is my world. And this is my love letter to L.A."

Quentin Tarantino incorporates the Rashomon Effect

In his 1950 classic, "Rashomon," Akira Kurosawa utilized a technique that would shape how future filmmakers tell stories: the "Rashomon Effect." In the courthouse drama, we're presented with the aftermath of a murder and rape. The film presents four eyewitnesses' varying accounts of who is responsible for these crimes. Through the unreliability of these recollections (done through nonlinear storytelling and flashback sequences), Kurosawa effectively examines the concept of perception. While each story seems plausible, we question if personal gain motivates the characters.

The Rashomon Effect has been used by various filmmakers such as David Fincher ("Gone Girl"), Park Chan-wook ("The Handmaiden"), and, of course, Quentin Tarantino. He's frequently taken inspiration from Kurosawa (like when the Bride cuts off Sofie Fatale's arm in "Kill Bill: Vol. 1," a direct nod to 1962's "Sanjuro"), but in his directorial debut, Tarantino expertly uses the Rashomon Effect when he turns his characters against one another, and they all wonder which one of them was the snitch responsible for their heist going awry.

"Reservoir Dogs" aside, Tarantino has also utilized this filmmaking style in his other movies like "Jackie Brown" in which the dressing room money exchange is shown from multiple perspectives.