Why John Hughes Hated Critics Calling His Actors 'The Brat Pack'

In the 1980s, no director respected and honored American teenagers as much as John Hughes. He believed teenagers took life seriously, and as a result, he treated their stories seriously.

Perhaps it's that earnest attitude toward teens that made Hughes bristle at one of the most famous nicknames for his actors, "The Brat Pack." In a 1986 interview in Seventeen Magazine, Hughes' star Molly Ringwald interviewed her frequent director and asked him whether the group's "obnoxious image" was deserved or a potshot at teenage actors who were just beginning to earn weightier roles. Hughes agreed that the term was an unfair label.

"There is definitely a little adult envy. The young actors get hit harder because of their age. Because 'Rat Pack' — which Brat Pack is clearly a parody of — was not negative. 'Brat Pack' is. It suggests unruly, arrogant young people, and that description isn't true of these people. And the label has been stuck on people who never even spoke to the reporter who coined it."

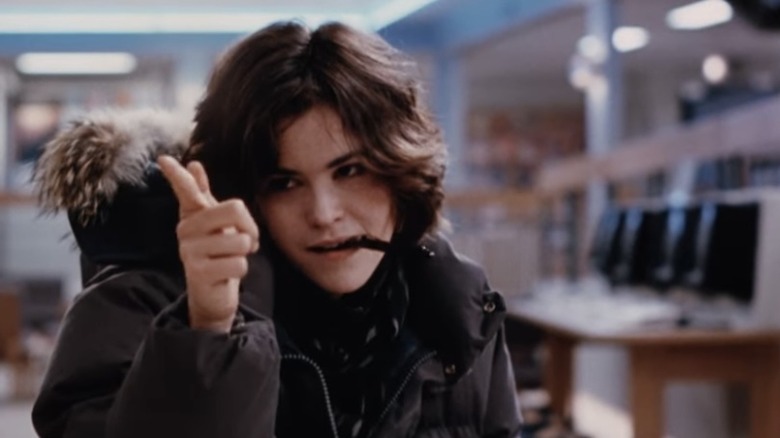

When New York Magazine writer David Blum coined the sobriquet "Brat Pack" in his 1985 cover story about breakout stars Emilio Estevez, Rob Lowe, and Judd Nelson, he imbued the term with macho intent. His description of "a roving band of famous young stars on the prowl for parties, women, and a good time" might have been an apt characterization of those actors' bacchanalian nights in Hollywood, but it missed the mark on Hughes' characters, which were more often sensitive portrayals of average, American teens dealing with mundanities of their suburban lives. And if there ever was a leader of the Brat Pack, it wasn't a young man, but Hughes' feminine muse, Ringwald. Hughes directed a trilogy of Ringwald vehicles including "The Breakfast Club," "Pretty in Pink," and "Sixteen Candles," with the latter's screenplay directly inspired by a headshot of the actress that her agent sent him.

Teen spirit

Hughes credited his ability to write sincere stories about young girls to his regular exposure to teenagers. When he was a father of two infants, his friends and coworkers already had adolescent children who could weigh in on his scripts. He also used his sister, nine years his junior, and her friends as inspiration for his writing. In a 1985 interview with Chicago Tribune critic Gene Siskel ahead of "The Breakfast Club" premiere, Hughes laid out his reverence for the American teen and his disgust with Hollywood's depiction of them.

”Many filmmakers portray teenagers as immoral and ignorant with pursuits that are pretty base...They seem to think that teenagers aren't very bright. But I haven't found that to be the case. I listen to kids. I respect them. I don't discount anything they have to say just because they're only 16 years old. Some of them are as bright as any of the adults I've met; all they lack is a personal perspective."

In the same interview, Hughes detailed his fascination with the teenage psyche and how their ideas, clothes, and tastes were constantly changing compared with adulthood's ossified state. He also noted that filmmakers were wrong about teenagers' attitudes toward sex and shouldn't make the mistake of applying mature sexual themes to stories about teenagers. His own actors, Ringwald and her fellow "Breakfast Club" star Anthony Michael Hall, often requested that he remove more explicit scenes from his films. As Ringwald told The Atlantic, Universal had pushed Hughes to include a scene showing a skinny-dipping female gym teacher in "The Breakfast Club". After several rewrites, he brought a stack of different drafts and asked his young cast members to piece together a script they preferred.

An ambitious picture

The final version of "The Breakfast Club" almost feels like a stage play. It largely takes place in one room, and focuses on five thoroughly fleshed-out characters whose stories unwind under the pressure of detention, hormones, and marijuana. In the wake of '70s slashers that punctuated raunchy teen sex scenes with their gory demise, the movie marked a turning point in cinema by showcasing a somber teen dramedy. With the exception of some horny escapades from Judd Nelson's character, the film eschews sex in favor of teen angst. As actress Ally Sheedy told Roger Ebert in 1984, "The Breakfast Club" succeeded because of what Hughes left out.

"Look at what this movie doesn't have...No high school dance. No chase scene. No naked shower scene. No beer blast. No rumble. It's about kids who are learning about themselves. It's like doing a play. It's an actor's dream. And it's an ambitious picture. With a lot of teenage movies, you get the feeling the filmmakers are remembering their own youth. This movie is about right now."

As Ringwald notes in The New Yorker, Hughes blazed a trail for teenage stories in an age before young adult novels exploded in bookstores and in film adaptations. Though written by a man in his 30s, the characters in his films sounded like teens of the time rather than the adult movie stars masquerading as them. He empathized with teenage girls and his movies captured their angst and heartbreak in a way that hadn't been captured on screen in an earnest way.

But even if Hughes proclaimed to write scripts that tended toward the chaste rather than provocative, his male teens' attitudes toward girls and sex have aged poorly to say the least. Ringwald and her co-star Haviland Morris, who plays Jake Ryan's blonde, popular girlfriend, caught up decades later to discuss a scene in which Jake states that he could violate his blacked-out girlfriend "17 ways if he wanted to." Ringwald expressed discomfort over the date rape joke, while Morris argued the scene was not that black-and-white.

"On the other hand, she was basically traded for a pair of underwear," Morris acknowledged. "Ah, John Hughes."

For a director who respected teenagers, Hughes had some blind spots when it came to his treatment of his female characters like Haviland's. In a post-#MeToo era where teens are engaging in frank conversations about consent, his high schoolers' antics can sometimes feel tone deaf. Despite the iconic roles he wrote for Ringwald and Sheedy, Hughes could at times subscribe to "The Brat Pack" archetype, one that embodied male arrogance and recklessness.