One Of The Scariest Scenes In The Original Stepford Wives Reminds Us That Our Bodies Aren't Our Own

(Welcome to Scariest Scene Ever, a column dedicated to the most pulse-pounding moments in horror with your tour guides, horror experts Matt Donato and Ariel Fisher. In this edition, Ariel gets horrified in Stepford, Connecticut, while Matt hides behind a white picket fence.)

I've never seen "The Stepford Wives" before this. I've been meaning to watch it, and what better time than now, while my mom who grew up in the '60s and '70s is visiting. And, you know, while Roe v. Wade is in the process of being overturned by a corrupt government that wants to control the bodies of people with uteruses.

Frankly, it just made sense. After all, what better place than here? What better time than now?

I can now honestly say without an ounce of hyperbole that "The Stepford Wives" is probably one of the more horrifying films I've ever seen, and that's likely only because I'm 34 years old. It's terrifying in the same vein as "Rosemary's Baby," which is appropriate when you consider it's based on a novel by the same author, Ira Levin. It's hard to pick just one scene, honestly. But I guess that's the point here.

"The Stepford Wives" works as a kind of moral litmus test. All I'll say is you should pay as much attention to the reactions of those you watch it with as you should to your own.

The setup

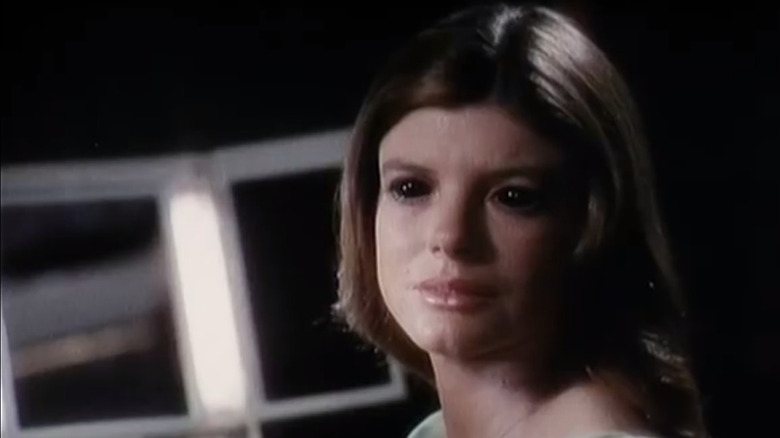

Joanna (Katharine Ross) and Walter Eberhart (Peter Masterson) pack up their Manhattan apartment and move to Stepford, Connecticut, with their two daughters, Amy and Kim (played by Ronny Sullivan and a 10-year-old Mary Stuart Masterson, respectively), and the family dog. Walter joins the local Men's Club (despite not caring for one very specific rule), Joanna meets the neighbors and gets interviewed for the local rag, and things quickly fall into a natural rhythm.

That is until people start ... changing.

Oh, nothing major, really. It just suddenly seems like the women of Stepford are losing their gumption as they gain more frills and a penchant for dusting. They also lose their personalities, intellect, and ambition for anything outside of the house.

The story so far

Everything is just so sanitized in Stepford, from the neighbors and their attire to the homes, lawns, and grocery stores, and Joanna does not fit in. She doesn't seem like the type to care, though, so that's not much of an issue. Except that she feels alienated in this new place, isolated from the rest of the world and the career that she loved (as a photographer).

Enter Bobby Markowe (Paula Prentiss). Another Stepford newcomer who's been there about a month, Bobby read about Joanna in the paper and immediately sensed a kindred spirit. The two bond over their mutual interest in feminist ideology, Ring Dings, and scotch (among many other things). They basically save each other from the doldrums of this suburban hell where folks are just too ... happy.

Well, the women are, anyways. The men seem fairly normal, relatively speaking.

She meets some of the members of Walter's Men's Club when they come over for drinks, including Dale "Diz" Coba (Patrick O'Neal), so-called because he used to work for Disneyland making animatronics. No, seriously. We're introduced to the character as he sits at his desk in front of a painting that looks like a Franz Kline. There's a rabbit hole here for me to go down another time, but we're getting to the scariness, so I'll hold off.

As the weeks roll on, things get stranger and stranger. Joanna and Bobby are sick and tired of their boring suburban neighbors who have nothing to talk about except how to cut down on wasted time while cleaning. Their attempt to start a consciousness-raising women's group first falls on deaf ears, and eventually leads to a disturbing scene where all the women can talk about is Easy On spray starch.

Walter spends progressively more and more time at the Men's Club, becoming more and more distant and detached. Their new friend Charmaine (Tina Louise of "Gilligan's Island"), another relative newcomer to the town, suddenly goes from playing tennis and speaking her mind to being a mindless drone clad in frills. Through some light research, Joanna and Bobby find out that every woman in Stepford used to be part of the women's liberation movement in some way, however minor.

A town full of strong-minded, independent women with opinions who all suddenly become mindless drones after living in Stepford for about three or four months? As Bobby puts it, there must be something in the water! So they contact an old flame of Joanna's named Raymond Chandler (no, not that one, but he is played by Robert Fields), a scientist who tests the water for them, only to find out that this town is clean.

By this point, Bobby and Joanna are terrified. Nothing makes sense, they feel like they're losing their minds, they have no idea what's going on anymore and they don't feel safe. Then Bobby goes away for a weekend with her husband, and when she comes back, she's not the same.

Now Joanna feels really alone. She goes to see a therapist at her husband's request (a chilling scene in its own right) only to be told to get the kids and leave town immediately.

She tries, but her girls have been taken, and she can't leave them behind.

The scene

Joanna makes her way to the Men's Club in the pouring rain. Ready for a fight, she sneaks into the severe-looking mansion, thunder and lightning crashing all around for that extra kick of pathetic fallacy.

The place is abandoned. She's all alone, and she can hear her daughters calling out for her in the distance. She follows the sound, only to wind up in Diz's office. He's seated in front of that Kline-esque painting, and stops the recording of Joanna's kids.

"Quite a lot of worry you caused everybody," he says, sitting up from his chair like a "Bond" villain.

Her kids are safe with Charmaine. She's there alone with Diz now, and he's locked the doors.

"It's nothing like you imagine," he tells her. "Just another stage. Think about it like that, and there's nothing to it."

"Why," she asks, breathlessly.

"Because we can," Diz answers. "We found a way of doing it and it's just perfect. Perfect for us and perfect for you."

He speaks about what we can only imagine is some kind of lobotomizing procedure as if women need saving from their own minds, from themselves. Deciding what's best for every single woman in town because feminism has supposedly caused such sorrow, and given the men such headaches. He talks about this procedure with the same casualness one might take a f****** Advil. It's equal parts chilling and infuriating.

Joanna's stunned into silence. It's as if the horrifying truth renders her almost catatonic. Until he comes to take her away, and she snaps to.

Bolting around the house, desperately looking for somewhere to run or somewhere to hide, she stumbles onto what looks like a soundstage of her own bedroom. Confused and disoriented, she doesn't know where to go anymore. Diz is coming closer as she's backed into the uncanny valley of her own home. Then she sees it.

Seated at a vanity brushing its hair ... it's her. Joanna. But something's very very wrong. This thing turns around to greet her, smiling its inhuman smile, its devilishly black eyes — a doll's eyes — piercing the silence. Its breasts are larger and perkier, its hips a little fuller, its figure a bit more robust. Its skin is fresher, its hair more luxurious — everything about this thing is like an idealized version of Joanna dialed up to 11.

And then it stands up.

It wraps a set of stockings in its hands as if they were a garrotte, slowly approaching Joanna with that smile. That sickening, inhuman smile.

Cut to black.

The impact (Matt's take)

Good horror carries social commentary in its clutch, and "The Stepford Wives" is no different. The gender constructs of how homemakers should behave, dress, and obey are terrifying when put to the screen like this, but it all hits harder when you think about reality. The facades of picket fences, perfect hairdos, and guidelines to being suitable arm candy are prime horror fodder in worlds where men make all the decisions. They're the breadwinners; of course, they should make rules about women's bodies.

Sound grossly relevant? It should.

The horror of watching Joanna realize she's about to be replaced by a Fembot is like watching someone's individuality being stolen just because of their sex. It's horrifying, this idea that lobotomizing your wife is more manageable than meeting her needs and treating her like a human being. These sound like far-flung nightmares cooked up by filmmakers as powerful plot devices — hell, even Zack Snyder tries it in "Sucker Punch" — but the world around us proves that these fears are still experienced almost five decades later.

A majority male Supreme Court still feels it necessary to dictate abortion rights in 2022, but go ahead and tell me horror movies have never been political, or that they shouldn't care about societal issues.

"The Stepford Wives" features a gender war that's unfortunately still a conversation, almost 50 years later. It's a great scene with poignant visual storytelling and drives home the impact horror can land when confronting realistic evils. Solid pick!