Why Every Movie Has Continuity Errors (And It's Really Not A Big Deal)

As those of us who used to browse the "Goofs" sections on IMDb for fun will know, movies and TV shows are absolutely rife with errors, both big and small. From the legendary Coffee Cup of Winterfell to Luke Skywalker's "Force kick" in "Return of the Jedi," they're everywhere — and the more closely a movie gets examined (especially in the internet era of screenshots, gifs, and frame-by-frame playbacks), the more mistakes will be discovered. Per MovieMistakes.com, Francis Ford Coppola's "Apocalypse Now" and Alfred Hitchcock's "The Birds" top the list of movies with the most mistakes spotted (with "Superman IV: The Quest for Peace" somewhat incongruously in third place).

The latest continuity error du jour involves an extra in a recent trailer for "Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness" — a man with a suitcase who is spotted frantically running past Doctor Strange ... and then running past him again, and again, and again.

Now, it's never a bad idea to pay attention to extras in a Sam Raimi movie, because there are almost always some absolutely golden moments happening in the background. But while Suitcase Guy has mostly been met with good-natured amusement and jokes about how he's trying to qualify for his SAG-AFTRA membership, there's also been some decidedly bad-natured attempts to present this particular goof as proof that "Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness" (and the Marvel Cinematic Universe in general) is sloppily-made.

But let's ignore the bad faith takes for now and answer some genuine questions people may have — chiefly, how does a $200 million movie have continuity errors?

What is a continuity error?

Let's answer the most basic question first. "Continuity" is the illusion that allows cuts in a movie to appear seamless, when actually the two shots we see may have been filmed hours, days, or even months apart. For example, one character throws a punch, and there's a cut to a wider angle in which the punch lands. In the second shot, we may not even be looking at the same two people; the actor getting punched in the face may have been stealthily replaced with a stunt performer, with the shot angled to hide their face. It's a grand magic trick with a whole crew of magicians collaborating to pull it off.

Perhaps because our brains are used to seeing continuous action in real life, they're fairly easily fooled into thinking that the action in one shot was immediately followed by the action in the next shot. Most of the time, we're not even consciously aware of cuts as we're watching a movie. As editor Walter Murch ("Apocalypse Now") wrote in his book "In the Blink of an Eye," the ideal cut "should look almost self-evidently simple and effortless, if it is even noticed at all." He describes the ease with which humans adapted to cuts in movies as a kind of miracle:

The mysterious part of it, though, is that the joining of those pieces ... actually does seem to work, even though it represents a total and instantaneous displacement of one field of vision with another, a displacement that sometimes also entails a jump forward or backward in time as well as space.

Murch goes on to explain that certain cuts have a greater tendency to disorient the film viewer, and from this emerged the "rules" of editing. One of the best-known rules is the axis of action, or the 180-degree rule, which dictates that if we're looking at two characters, the "eye" of the camera must remain on one side of them. If a character is on the left side of the frame and the eye of the camera suddenly jumps to the other side, so that they are now on the right, the result is jolting for the viewer. Suddenly, they are aware of the cut. Murch continues:

The discovery early in this century that certain kinds of cutting 'worked' led almost immediately to the discovery that films could be shot discontinuously, which was the cinematic equivalent of the discovery of flight: In a practical sense, films were no longer 'earthbound' in time and space ... Discontinuity is King: It is the central fact during the production phase of filmmaking, and almost all decisions are directly related to it in one way or another — how to overcome its difficulties and/or how to best take advantage of its strengths.

How are continuity errors prevented?

Keeping the camera on the same side of the actors is a fairly simple rule, and difficult to get wrong (though some filmmakers break the 180-degree rule on purpose, in instances where they want to disorient the viewer). But continuity goes far beyond camera placement. In order to have perfect continuity, everything must remain the same: the characters' placement in their environment; their distance from one another; their eyelines; their costumes (and any stains or tears); their make-up; the motion of their bodies; the emotions on their faces; the length and style of their hair, and how it lays on their faces and bodies; the length of their facial hair (if any); the placement and details of their tattoos (if any).

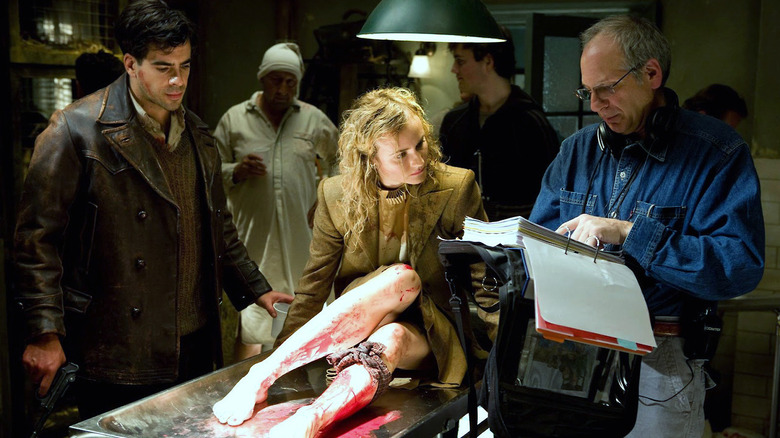

And all that is just the continuity of the main actors. What's happening around them is a far greater continuity nightmare. If there's a clock on the wall, the time on the clock needs to be consistent across shots and also match the time of day as conveyed by the dialogue and lighting. If the characters are eating food, the number of bites taken needs to be monitored (the actor took a bite from a burger but the take was no good? You're going to need a new burger for the next take). If it's sunny in one shot, you can't then cut to a shot where it's clearly overcast; lighting and shadows need to be matched across shots, even if you're doing reshoots a year after the scene was first filmed. If you're making a gory horror film, the quantity and splatter patterns of the fake blood need to be consistent across shots.

Needless to say, matching continuity is not a one-person job. The script supervisor is responsible for overseeing continuity on a film set, but it's really a work of massive collaboration. The hair and make-up department will take hundreds of reference photos that they must work from to ensure that, for example, the lead actor's winged eyeliner looks exactly the same on each new day of filming. Between takes, an assistant director will call the make-up artist back in for touch-ups to freshen up faded lipstick and powder foreheads that have become sweaty. The costume department must ensure that a shirt that gets torn in one shot has an identical tear in the next shot. The props department take detailed photos of every corner of the set to ensure that they can recreate the exact arrangement of porcelain figurines on a dresser if they need to. If the scene is being filmed outside on a sunny day, a runner will have to hold an umbrella over the actors between takes to ensure they don't get a sunburn. And all of these people have to do all of these things throughout filming days that may last 12-14 hours or more.

Like many aspects of filmmaking, continuity is a ridiculous endeavor: an attempt to force order on a process that's inherently chaotic. Background performers in particular add so much chaos that extras actually have their own director (typically the second or third assistant director) who is in charge of telling them where to stand, where to run, and how to react. Getting the main actors to hit their marks consistently is tough enough as it is; if you have dozens of extras in play, there simply isn't time to micromanage precisely where each and every one of them is in every second of every single take — even if you did know in advance exactly which takes the editor would be selecting and how they'll be edited together months down the line.

The inherent chaos of the multiverse

By now it should be clear why massive blockbusters like "Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness" are actually more prone to continuity errors than low-budget indie movies. The more moving parts you have, the more potential for chaos there is. If absolutely everyone is doing the best possible job that they can under the circumstances and problem-solving perfectly when things go wrong, you may be fortunate enough to end up with a movie that's 98% flub-free.

The mistakes that slip through in that 2% are the kind of mistakes that you'd typically never notice on a first viewing in the theater. There's simply too much new information to absorb for your brain to have the time to go poking around in the corners. The more times you view a movie, the more things you'll notice — from Easter eggs, to clever foreshadowing, to the same extra running past Doctor Strange four times. In theory it might be possible to create a movie that's 100% free of continuity errors ... but the extra time and labor involved would probably balloon the budget to ludicrous proportions. Productions will go back and do reshoots for scenes with particularly egregious continuity errors, but if it's something that moviegoers are unlikely to notice without close scrutiny, it's just not worth the expense.

While continuity errors are sometimes lambasted as "lazy," goofs like these are actually more often an indicator of how challenging a shoot was. It's no surprise that "Apocalypse Now" tops the list of movies with the most mistakes, given that its production was such a nightmare that a whole other movie was made about what a nightmare it was. So if you happen to spot a boom mic dipping into frame, or a stormtrooper bumping his head, or a gas-powered Roman chariot, just appreciate these things for the little peek beyond the veil of filmmaking that they are.