The Last-Minute Change That Saved Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho

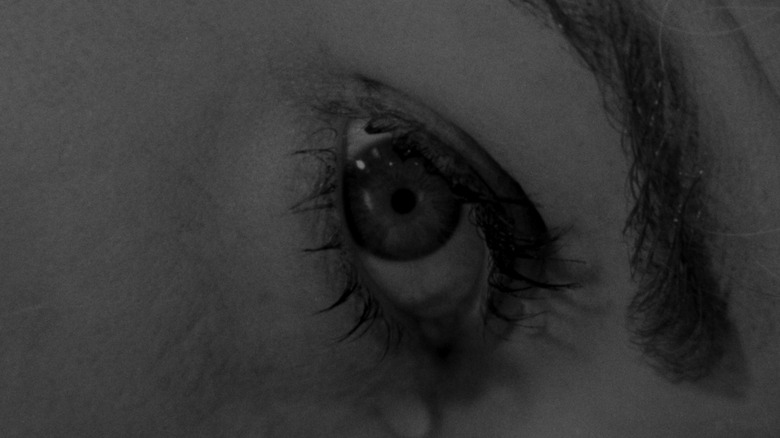

A young, attractive woman steps into a running shower and closes the curtain behind her. She shuts her eyes, enjoying the hot water, and turns her back to the closed curtain. Suddenly, the screeching sounds of string instruments rise over the scene. Do you know what comes next?

Chances are, without seeing a looming shadow or a single drop of blood, you guessed murder. How did you know? Because the music told you.

The sound of shrieking strings is one of the most imitated and recognizable themes in the history of film. Ever since the sound cried out over the murder of Janet Leigh in "Psycho," it has come to mean impending doom, a sure sign that something wicked your way comes, and there is no escaping it.

Although the theme has become synonymous with murder, it breathed life into a film Alfred Hitchcock thought was dead in the water.

An expected failure

Hitchcock was already known as "The Master of Suspense" when he pitched the idea for "Psycho" to Paramount. The film would be an adaptation of Robert Bloch's novel of the same name, which he'd based on the murders of Ed Gein, the guy that would later inspire "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" and "The Silence of the Lambs." This was way before slashers were even a thing and the studio was certain such disturbing material would lead to a box office failure, so they refused to fund it.

Hitchcock wouldn't take no for an answer, and in exchange for 60% of the profits, he offered to pay for the project himself. Paramount gladly took that deal. If life had a soundtrack, the studio executives would have heard those rising, screaming strings as they shook hands with Hitchcock, because it would turn out to be a terrible deal for them.

The director would use his money wisely, hiring the already established TV crew from "Alfred Hitchcock Presents" and building cheap sets from repurposed material. The whole production only cost $806,947 to make. This was considerably less than the average film budget at the time of $1.5 million. Despite his determination and passion for the story, when Hitchcock saw the raw footage, he thought the movie was a failure.

Reportedly, he was so disappointed by what he saw, he was ready to "cut it down to an hour television show and get rid of it." The director would turn the footage over to Bernard Herrmann, the film's composer, and go away for Christmas.

This is when screenwriter Joseph Stefano insists, "Bernie took the picture and turned it into an opera."

The sound of disobedience

Hitchcock liked to be in control and left specific instructions with Herrmann about music placement in his movie, saying, "Do what you like, but only one thing I ask of you: please write nothing for the murder in the shower. That must be without music."

To modern audiences that seems like an absurd idea, but Hitchcock was known to use silence as effectively as sound. For example, this scene in "North by Northwest" uses the lack of sound to heighten the suspense as Cary Grant stands by the side of the road in the middle of nowhere. The preceding silence heightens the action when Grant is almost dive-bombed by a crop duster a few moments later. This is the effect Hitchcock had in mind when he first thought about the shower scene in "Psycho."

Herrmann had other plans and created a theme for the scene anyway, but kept it to himself.

Hitchcock screened the edited film four times with screenwriter and former composer, Stefano, who later admitted the first three times were awkward because the movie "did not seem to be working." Both men were frustrated by this outcome, which led Hitchcock back to Herrmann. The composer thought this was the right moment to admit he'd disobeyed the rules and played Hitchcock the now-famous theme, "The Murder."

The fourth time Stefano and Hitchcock screened the film, Herrmann's music was included, and Stefano was blown away by the effect of it:

"When I heard it, I nearly fell out of my chair. Hitchcock said the music raised [the impact of] "Psycho"... 33 percent. It raised it for me by another thirty ... It was so breathtaking that I gasped."

The director would admit that his original desire for silence was an "improper suggestion" and the shower scene as we know it today, with its hair-raising string music was born.

The low-budget movie that everyone expected to fail was first seen in New York on June 16, 1960. It was an instant success and earned $15 million in a year. Along with being a box office hit, "Psycho" would prove to be revolutionary. The film broke Hollywood taboos and pushed censorship rules that would pave the way for franchises like "Halloween," "Friday the 13th," and "Scream."

Just when you thought it was safe...

Beautiful women being murdered by creeps isn't shocking anymore. Pick a slasher flick, any slasher flick, and I guarantee you the killer guts his fair share of women. Back in Hitchcock's day, this wasn't the case.

Pre-1960s America still liked to see itself as wholesome and respectable, the kind of place you can leave your door unlocked. It wanted this self-image reflected back in all aspects of the culture, which is where the Hays Code came in.

The code was a set of rules handed down by censors that all motion pictures had to follow. As we've already discussed, people who worked on "Psycho" weren't fans of following rules, so Hitchcock pushed the limits of the code as far as he could. The censors found the nudity and violence of the shower scene scandalous. They were certain they had caught a glimpse of a breast (the horror!) or blood, but Hitchcock played the scene for them over and over, frame by frame, and they realized their brain had tricked them into thinking they'd seen those things.

The scene would technically pass the censorship code because you don't see nudity, violence, or blood, the camera angles and suspenseful theme just convinces your brain that you do. Your own imagination fills in the gaps of brutality and nakedness, forcing you to confront your own violent ideas, and the fact that "we all go a little mad sometimes." This was an incredibly shocking exercise for apple pie America.

"Psycho" does not show any of the typical horror movie gore, but it was the much-needed first step on the path to horror films that are covered in blood and guts. It introduced American audiences to graphic violence and made murder an acceptable plot point. I won't go so far as to say Hitchcock made violence cool, but he definitely made it interesting. His revolutionary film would contribute to "Black Christmas," "Halloween," and countless other movies we now call slashers. Its influence can be seen everywhere: Drew Barrymore's unexpected demise in the first 15 minutes of "Scream," the empty stare of the soft-spoken obsessive serial killer, Donny Pfaster, in "The X-Files," just to name two examples.

While its visual legacy cannot be understated, the film forever altered the audience's relationship with sound. "Psycho" showed us that the murder of a beautiful woman looks like a ripped shower curtain, a shadowy figure welding a knife, and a hand reaching out for help that isn't coming. It also taught us that it sounds like running water, the suction of a drain, and screaming strings.