The Henry & June Controversy Explained: The First NC-17 Movie

If you've ever doubted the power of film, look no further than the influence of the Motion Picture Production Code. Better known as the "Hays Code," named for the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) president Will Hays, the regulations steered Hollywood studios in a wholesome direction, creating an idyllic cinematic portrayal of America that existed throughout the Golden Age of cinema. Hollywood can often subvert our memory, creating concrete images of a bygone era, long before every part of our mundane lives were documented on social media. When we use Hollywood as a timestamp of the first half of the 20th century, it is done through the squeaky-clean lens of the Hays Code.

Though the Hays Code would eventually become obsolete, the new Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) rating system was not without controversy. In 1990, a new rating meant to disassociate Hollywood from the pornography industry almost backfired while putting a dark cloud over a movie's release. As the first-ever NC-17 (no one under 17 admitted) film, "Henry & June" would inadvertently bring Hollywood full circle to its roots of censorship.

How we got to NC-17

Hollywood has a long, sordid history when it comes to its rating system. The film industry became a means of artistic expression throughout the 1920s, but after outcries from religious groups, state censorship boards began cutting controversial parts from movies and Hollywood would begin to lose its voice. In 1930, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) created the Motion Picture Production Code, a set of self-imposed guidelines meant to avoid controversial content, including certain types of profanity, violence, and sexuality.

Though the code was considered "self-regulation," Catholic priest Daniel A. Lord had a heavy hand in creating the new guidelines. The code was meant to shift America to a more conservative bent on the heels of the Great Depression. ACMI film curator Chelsea O'Brien explains:

"With less money in people's pockets for movie-going, studios tried luring audiences in with salacious films featuring sex, violence, drinking and the grotesque, like "Baby Face" (1932), "Scarface" (1932) and "Freaks" (1932), whose storylines reflected glamorous gangsters, sexually-liberated women and class struggle. It's no wonder the Hays Code was conceived during this period."

Throughout the 1960s, the code would begin to lose its grip on studios. The growing popularity of television and foreign films, coupled with a court ruling giving movies First Amendment protection, led to the death of the code. In 1968, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) rating system we're familiar with today officially replaced the restrictive "Hays Code."

The most severe rating the MPAA could assign was an adult-only X-rating, warning of violence, language, and sexual situations inappropriate for children. Most studios would purposely avoid an X-rating to maximize box office potential, leaving pornography most associated with the X-rating. In 1990, the MPAA sought to change that with the new NC-17 label. It didn't take long for a film to see if the rating change would be a success.

And with that out of the way, we get to "Henry & June."

Show the film and lose your license

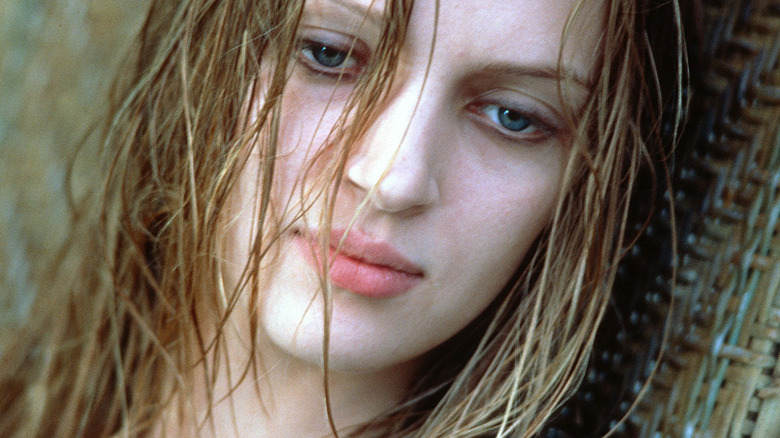

On September 27, 1990, the MPAA announced the NC-17 category, describing it as "one step up from an R-rating." Just eight days later, "Henry & June" debuted as the first NC-17 film in theaters. The Phillip Kaufman-directed drama starring Fred Ward and Uma Thurman centers around a love triangle between a novelist, his wife, and another woman. "Henry & June" didn't do the MPAA any favors in their effort to separate Hollywood from the porn industry by marketing itself as a "daring, erotic masterpiece." Although there are plentiful sexual scenes to warrant the NC-17 rating, Kaufman layers them with artistic cover.

It didn't take long for the backlash over "Henry & June" to begin. In what seemed like a return to the religious-inspired restrictions of the "Hays Code," the History Channel notes that on October 13, a Boston suburb removed the film from its schedule after local officials threatened to pull the theater's license. Additionally, religious radio and television stations opposed the new rating, and a newspaper in Birmingham, Ala., announced it would not accept advertisements for NC-17 films.

"Henry & June" survived the short-lived controversy surrounding its release. The film opened in 76 theaters across the country in its first week, grossing nearly a million dollars, and was later nominated for an Academy Award for Best Cinematography. However, an implicit bias looms over the NC-17 rating to this day.

Since the advent of the NC-17 rating, only three films hit with that label have received Oscar nominations in any category, and none have won. In addition to "Henry & June," 1990's "Wild at Heart" (Best Supporting Actress, Diane Ladd) and 2000's "Requiem for a Dream" (Best Actress, Ellen Burstyn) are the only others. While modern filmmakers could conceivably see more commercial success with NC-17 movies in the age of streaming, they still face scrutiny when it comes to recognition of the artistic merits of their work that is deemed for "adult eyes only."