Year Of The Vampire: Near Dark Is A Western Horror That Reworks The Captivity Narrative

(Welcome to Year of the Vampire, a series examining the greatest, strangest, and sometimes overlooked vampire movies of all time in honor of "Nosferatu," which turns 100 this year.)

When Amazon deigned to stream Kathryn Bigelow's 1987 film "Near Dark," it advertised it with the tagline "Before Twilight, before True Blood, there was Near Dark." Yes, it was indeed released prior to 2008, but this is otherwise bullcrap. If you are a "Twilight" fan checking out "Near Dark" on this recommendation, you are likely to find the main romance between a vampire and a human to be anemic. If you are a "True Blood" fan doing the same, you will be further unimpressed by its treatment of race and sexuality in comparison with the HBO series. This isn't because "that touchy feely 'Twilight' garbage" is superior to what "Near Dark" has to offer, but rather because there are fundamental differences in genre and audience between them. Put simply, "Twilight" and "True Blood" are paranormal romances, whereas "Near Dark" is a Western horror film.

Put a lot less simply, "Near Dark" has its own unique and compelling messages about desire, love, and sexuality, but they make very little sense if you try to understand them through the conventions of a genre that was in its nascent stages when the film was made. Paranormal romances are largely female power fantasies about dangerous and threatening monsters restraining themselves out of love for and/or attraction to human protagonists. They're an extension of more traditional romance tropes about rich and powerful men falling for women who are usually lower down the socioeconomic ladder. That "touchy feely garbage" is often a nuanced and fine-grained attempt to grapple with inequalities and fears that don't have solutions outside of fiction. (It is possible that I am punchy after a decade and a half of hearing about how society and/or the horror genre is going to collapse because girls are watching "Twilight.")

Within the Western genre, "Near Dark" is one of the more recent film installments of a very old American literary tradition. It's a captivity narrative, evolving out of semi-fictionalized 17th-19th century personal accounts into frontier fiction such as James Fenimore Cooper's "The Last of the Mohicans" and then into classic Western novels and films like Zane Grey's "Riders of the Purple Sage" and John Ford's "The Searchers." Their plots revolve around dangerous hostiles kidnapping innocents and forcibly assimilating them unless a noble hero saves them, and they are often inextricably tangled up with how male characters define themselves.

If you can't protect the ones you love, you're hardly a man. If you can somehow save your wife or niece or daughter from awful treatment at the hands of terrifying Others, you've proven yourself superior to those Others. "Near Dark" swaps out the Hurons, Comanches, and Mormon polygamists for vampires, which does a lot to improve the awful racist and religious stereotypes that are practically guaranteed with these stories. However, it also doubles down on the swirling fears of sexual assault and transformation that underpin these stories, turning them into something much weirder and terrifying.

What It Brought to the Genre

"Near Dark's" primary influence on vampire film is syncretism, which is a fancypants way of saying that it took existing elements of disparate things and fused them into something new and entirely different. It went back beyond the decadent aristocrats of the late 19th century to the undead things scuttling around Eastern European graveyards and combined them with the drifters and lowlifes roving around the American Southwest in the 1970s. (Check out Jesse's fingernails, for one.) They remained sexy, but a good coat of grime made them hot in a dirty, creepy, weirdly compelling way, far from any tuxedos or filmy nightgowns. It took the nuclear family bound together by love and familiarity and combined it with something closer to a wolf-pack hierarchy to create a thermonuclear family constantly at risk of fission. Above all, it took the primordial white American fear of People Not Like Us and neatly flipped it into a fear of People Who Used To Be Us.

Vampires, after all, are relatively unique among monsters (or at least the monsters that you'd want to have sex with) in that they were once humans like us, with our basic habits and beliefs and political affiliations and so forth. ("True Blood" gleefully takes this premise and runs with it; "Twilight" incorporates it in the most boring manner possible.) They're unnerving precisely because they are no longer us but are instead predators who feed on us and occasionally want something more. We can still recognize what they once were in a kind of uncanny valley, but there is a much sharper divide between us and them than between us and another group of people, no matter how much we might want to convince ourselves that those people aren't really people. In recognizing the former humanity in vampires, we have to confront some deeply uncomfortable things about ourselves.

Flipping the Captivity Narrative

In its reworking of the captive narrative, "Near Dark" asks some unsettling questions: what if the hero is actually the captive? What does it mean if those hostiles are threatening a man, transforming him into something else, making him the one who needs to be rescued? What does that say about them, and us, and him? Most important, what does it say about him that he loves the person who has forced him into this role?

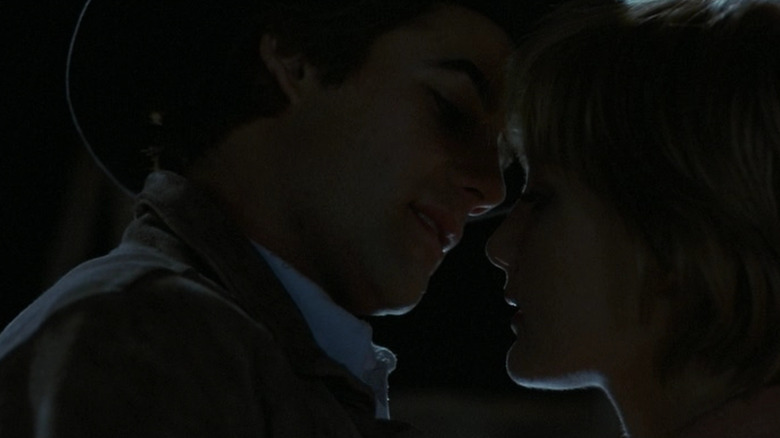

That Caleb falls for Mae the second he sees her is no surprise; she's played by Jenny Wright walking slowly in cowboy boots to a Tangerine Dream score in one of the best male-gaze sequences I've ever seen. What Mae sees in him is dinner, but it helps that he's played by Adrian Pasdar. Fortunately, Mae won't be able to listen to "Gaslighter" for another 33 years and is therefore blissfully unaware of what that entails.

There's no discussion of her being his personal brand of heroin or providing blissful psychic silence or even anything beyond a bland "You sure are pretty," but that tells us nearly everything we need to know about Caleb, a simple and straightforward guy with no apparent direction or ambition beyond a desire for a girlfriend. When we first see him, he's chilling in the bed of his truck getting bitten by the Mosquito of Foreshadowing; he doesn't seem to have a job or any mission beyond going to the local bar for a drink with his friends.

He does reveal himself to be not exactly a nice guy — West Oklahoma Caleb, if you will — when, after a night of what he thinks is Mae playing hard to get, he refuses to take her home unless she kisses him again. It isn't the worst thing that can happen in the cab of a pickup with a guy who feels entitled to whatever he wants, but it's still coercive and creepy. This is after she's freaked out about the impending dawn and begged him to get her home as quickly as possible, and also after an impromptu astrophysics lecture in which she's said that she'll live forever. Caleb is actually the one imperiled in this situation, as he's sitting there with a hungry and terrified vampire. To borrow a term from another of Pasdar's films, the risk quotient in this scene is inverted.

"Near Dark" is full of scenes like this, in which what we expect gets turned upside down. What initially looks like a standard makeout session is instead a metaphor for the way one brief sexual encounter can change your entire life irrevocably, which women have understood forever and straight men were belatedly waking up to in 1987. What looks like a little boy is actually a crotchety old-man vampire. What looks like hitchhikers menacing two middle-aged motorists is actually the worst decision put on film since the Weyland-Yutani Corporation decided to research Xenomorphs. Our ostensible hero is the one who gets abducted by savages, and the standard vampire trope of brave men rescuing helpless women from evil undead monsters gets flipped hard, as Caleb is now very much Severen's potential breakfast and Mae is the one who saves him.

Which raises the question: why, exactly? Mae never explains what sets Caleb apart from the estimated 1,460 previous nights of cute dumb guys falling for the whole soft-serve cone routine or why she spent an entire night struggling with her own personal dictum of "don't think about it, just kill." Obviously, Mae is lonely. All she's had for company for the past four years is the creepy little kid who turned her, an aloof older couple wrapped up in their own closed-circuit romance, and everyone's favorite Psychotic Vampire Nightmare Guy, but we don't ever get any specific reason why Caleb is the one with whom to spend eternity. By traditional romance standards, this is woefully underdeveloped; by paranormal romance standards, this is missing the point.

In a Western, especially a captivity narrative, this is baked in. In stories like "The Searchers" and the real-life incidents on which Alan May based it, Native Americans abduct women and girls and kill the men trying to protect them. Men and boys have no utility at all; young women are valuable for sex, which is what eats up Ethan Edwards' brain throughout the entire film. In "Near Dark," Mae has set up a situation where Caleb is bound to her and needs her ("I can teach him!") with zero consent beyond him abstractly mentioning that it might be kinda nice to live forever. This was presumably not what he had in mind when he said that he wanted a girlfriend.

That Caleb is extremely down for anything physical with Mae doesn't make this dynamic vanish, but the film reduces it a whole lot when she warns him that he could kill her if he drinks enough blood from her wrist, putting them on slightly more equal footing. It also helps that she's about as unthreatening as possible. Wright is a lot more femme than fatale, and she is much more of a Groom's Little Sister than a Bride of Dracula. She has an additional problem in that she plays both the love interest and the person who has set the horror elements of the plot in motion. In order for the romance to function, we need threat and menace and amorality from someone other than Mae.

The Queer-Coded Vampire

Bill Paxton's Severen, bless his heart, is possibly the least-conflicted vampire ever, and he spends the entire runtime of "Near Dark" living his very best afterlife. He does what he wants when he wants, and right from the second that he shows up, what he wants is Caleb. Initially, he's only looking for breakfast, but in pretty short order, his interest goes other places, including one particularly unnerving reference to "getting my wet dream tonight!" There is a truism that straight men are afraid of gay men because they're afraid that gay men will treat them the way straight men treat women, but that isn't what's going on here. For one, I couldn't begin to assign a sexual orientation to Severen if I tried. The closest he comes to not being down for whatever is to complain that he "don't like it when they ain't been shaved!" which still doesn't dissuade him even if the guy in question did "smell like a dead polecat." For another, he treats women very differently than he treats men.

(For those of you about to lecture me about how I am reading too much into "Near Dark," the explicit association between queer sex and male vampires feeding on men goes all the way back to "Dracula." In fact, Bram Stoker even requested that the American edition specifically include a reference to Dracula feeding on Jonathan Harker; it doesn't appear in the British edition. He apparently thought that American audiences would be more receptive to homoeroticism based on his reading of Walt Whitman's poetry, which, okay. Are you going to argue with Bram Stoker about vampires? I didn't think so.)

Even given that, "Near Dark" isn't exactly homophobic, despite being made in 1987. Though there aren't any AIDS burgers available, its queer-coded character is arguably the real center of the film. This is mostly because Paxton is more fun than should be legal as Severen, and the sheer delight he takes in wreaking havoc everywhere he goes is one of the best parts of the film. We don't get to know any of his victims and don't care about them — including, worryingly, the two lovely ladies he charms — and we mostly get a vicarious thrill in watching him lay waste to a roadhouse. He wants to feed off of Caleb, with all that entails, but what he really wants is for Caleb to be part of the family. The roadhouse scene is more akin to hazing ("I wanna show the kid something!"), and when Caleb manages to redeem himself later as a getaway driver, Severen is magnanimously generous, even giving Caleb one of his spurs.

A Good Western Protagonist, a Terrible Vampire

The real danger to Caleb is not that Severen will feed on him or even assault him but that Caleb will lose all of his remaining humanity and become like him. Ethan isn't wrong to recognize that losing your identity in all of the myriad ways that it's formed is the worst thing that can happen to you while you're still alive. (What he plans to do about it is another story entirely.) People can hurt you in awful ways, even kill you, but the real horror is losing everything that makes you you – your culture, the people who love you, your language, your very way of life. Any time spent reading captivity narratives will eventually reveal Cynthia Ann Parker. She was one of the women on whose life May based "The Searchers," and she starved herself to death in 1871 after the Texas Rangers kidnapped her back as an adult from the Comanches who had abducted her as a child.

What a lot of viewers have interpreted as Caleb being a wet noodle or Pasdar being a bad actor is actually Caleb's shock and trauma at suddenly being something completely alien to himself, with the awareness that he could very easily lose himself entirely. Yes, he's scared; as quite a lot of people have been lecturing me since 2008, vampires are supposed to be scary. It's not as flashy as Paxton's performance, but it's no less detailed than Pasdar's later turn in the Vantablack drama "Profit," which I and about five other people watched back in 1996 before Fox canceled it and took all of his microexpressions away from my TV screen.

Caleb's steadfast refusal to give up his humanity may make him a solid Western protagonist, but it also makes him a consistently terrible vampire, incapable of feeding directly on anyone and needing Mae to provide an acceptable source of blood for survival. This gets us the closest that "Near Dark" provides to a sex scene, full of phallically pounding oil wells and Caleb sprawled out in what could only otherwise be a postcoital state. It also drives Severen bonkers. Caleb either needs to fully commit to being a vampire or he needs to be a tasty snack; he has to go entirely into the night and can't exist perpetually in twilight.

Transformation

Which gets us to the weirdest and most unusual part of "Near Dark," which is that vampirism is a relatively easy process to reverse. All it requires is a blood transfusion from Tim Thomerson's manly dad arms in a process that makes absolutely no logical sense and all of the metaphorical sense. Caleb is now human again, having survived among the hostiles and maintained his moral superiority. In the most profound inversion of the film, he's come out of an experience that's almost exclusively the province of young women as a much stronger man. He doesn't need his dad's help to kill Severen or rescue his sister Sarah from Homer's predatory designs in the backseat of a car, though she does a solid job of rescuing herself by clocking him in the head with a Maglite. Jesse cannot protect his beloved Diamondback from the Oklahoma sun, but Caleb manages to save both Sarah and Mae. We are back in very, very familiar Western territory.

And yet: love may not be love which alters when it alteration finds; but in paranormal romances, the alteration is the point. Either the monstrous love interest changes himself for the human protagonist, modifying his behavior so that they can have a relationship, or the human protagonist eventually becomes a monster to share an equal life with her lover. In a Western captivity narrative, the goal is to rescue the loved one and bring her home safe and unchanged by her ordeal, if at all possible. That Caleb's experience has altered him for the better and turned him into the hero is a very odd commentary on the nature of that experience, harrowing as it was. Becoming a vampire made him understand what it was to be human, and especially what choices are necessary to stay with the ones you love. It has also made him realize what it really means to love someone without coercion or manipulation. Mae has obviously figured out the same thing, which is why she makes a similar choice by saving Sarah.

When Mae bombs out the back of the station wagon with Sarah in her arms, she has every expectation of dying, which is her real sacrifice. Rejecting her vampire family is rather less of a concern. Earlier, I referred to Jesse's crew as drifters, which isn't really accurate. To drift implies a current by which to be pulled along. "Near Dark's" vampires move in something closer to Brownian motion, where particles bounce off each other at random. They feed every night and then flee in yet another stolen vehicle, relying on the ineptitude of small-town cops to escape. For all that Mae says "we can do whatever we want," they have a grind that redefines Sisyphean. It might be nice to occasionally have a change of clothes, if we're feeling really off the chain. Also, I miss Bill Paxton desperately, but spending a century with Severen looks exhausting.

Ultimately, it's less about what Mae is giving up than what she is gaining. After the events of the past two years, I am confident in saying that the most fantastical element of "Near Dark" is the ability to reintegrate yourself after trauma. It's not a cop-out, as an early reviewer sneered. It's what we dream about when we're going through strife and misery: this will be over someday; life will be better; we will be better. This isn't a simple fantasy of reversal, either; things will not be the way they were. When Caleb tells Mae that he's brought her home, he doesn't mean Sweetwater, TX but rather Fixx, OK.

The Western fantasy of being man enough to save someone you love rarely takes into consideration what saving really means. It's not enough just to rescue someone from immediate peril. If you really care about them, you'll do whatever is necessary after the glamorous part to ensure that they are genuinely complete again and don't have to live in fear. For Ethan, that means staying outside and away from Debbie. For Caleb, it means coming inside to reassure Mae that dawn is no longer death and the light streaming across the threshold is a new beginning. Pray for daylight.