We Need To Talk About Cosby Director W. Kamau Bell Talks Separating Art From The Artist [Interview]

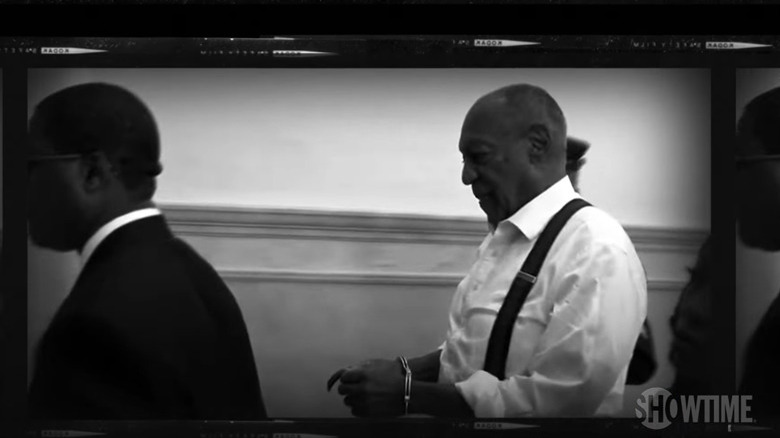

If you subscribed to Showtime to see what all the "Yellowjackets" buzz was about, make sure you hang onto that subscription. The premium channel is about to be the home of "We Need to Talk About Cosby," a four-part documentary series from comedian and director W. Kamau Bell. The doc series debuted a few days ago at Sundance, and it is a spectacular piece of cultural criticism that tries to reconcile all of the good that once-beloved comedian Bill Cosby did as a trailblazing television icon (especially for the Black community) with the dozens of allegations of rape and sexual assault that have been levied against him in recent years. It's a powerful series that takes the time to go deep, charting and contextualizing Cosby's rise through the entertainment industry while also providing a much-needed platform for his accusers to share their horrific experiences with the man.

I recently had the pleasure of speaking with W. Kamau Bell about finding a home for this show, separating the art from the artist, and the big takeaway he hopes everyone has after watching the series.

"It wouldn't have made sense to try to pull this off in feature length."

I want to ask you a logistical question to start with. There's an almost inconceivable gulf between Bill Cosby's public persona and his private actions. How did you figure out how long this project needed to be in order to properly contextualize that gap for viewers?

When I think about two projects that affected me before I ever thought I would actually be in a position to do something like this, key touchstones of this project were Ezra Edelman's "O.J.: Made in America" and Dream Hampton's "Surviving R. Kelly." So that showed that if you want to tell a complicated story, if you want to tell a story that goes over many, many, many years — decades in the way of OJ's story or complicated in the way R. Kelly's story also goes over decades, [although] not as many decades as Bill Cosby — and you also want to incorporate the story of America, that person's story, the story of why the story's being told, which is both Bill Cosby, the sexual assaults and rapes that I believe he committed, and the story of America, you need multiple parts. So it wouldn't have made sense to try to pull this off in feature length. I think if that had been the option, I wouldn't have done it. It wouldn't have made sense.

You've done work with places like CNN and FX before. How did you decide that Showtime was the right fit for this?

It's funny, I've been around in this business long enough that the thing they say is true: Make sure you're nice to everybody. So Vinnie Malhotra, who is in charge of this project at Showtime, was one of the people at CNN who was like, "Maybe we should give this comedian a shot to do a show called 'United Shades of America.'" According to Vinnie, he's the one who said, "Why don't we look at Kamau for this show?"

Made in America

It's interesting that you bring up "O.J.: Made in America," because I thought about that project a lot as I was watching this, especially since this is ostensibly about one man but ends up zooming out and showing this much more macro view of what was going on. Were there other influences that you had here aside from that and "Surviving R. Kelly," whether from a narrative or visual level?

Yeah, I just want to be clear that I think "O.J.: Made in America" is one of the best creations that an artist has ever made. I would say if you're at the Sistine Chapel, make sure you stop by and see "O.J.: Made in America" on your way. [laughs] It's like an epic achievement. So certainly "Surviving R. Kelly," "O.J.: Made in America." We were in production when "The Last Dance" came out and so some of the talk about how we used our timeline was informed by how it worked in "The Last Dance" — not that there's any other comparison between those two than that. But just as far as a way in which you can make sure people — because when you're telling a story that goes over this many years, you're trying to go, "Let's go this far and then go back to explain another thing that was going on during this time," you need some sort of visual timeline device. So "The Last Dance" was really a part of that.

At one point, I showed a cut of this to my wife, Melissa, early on and she was like, "I know what you told me you're trying to do. This isn't it yet." And then I showed it to a friend of mine, Kate Schatz, who is the author of the book "Rad American Women A-Z." And she was like, "I feel like it needs more you in it." And I was like, "No, no, no. This is like 'O.J.: Made in America.' It's not going to have me in it." And then Vinnie from Showtime saw the cut and he was like, "You need to be in this." And so I had all this feedback about how I wanted to be in it [while] I was myself was like, "This is the first time I'm going to be completely behind the camera in a project that I'm doing," or one of the few times. So I wrestled with that. But then one of the greatest docs I've seen in recent years from a filmmaker who I respect a lot is Alex Gibney's Theranos doc, "Out For Blood in Silicon Valley." That doc, he narrates it, and he's not doing it as personally as I'm doing it, but there is a sense that Alex Gibney is leading you through this. Not just some random narrator — this is an Alex Gibney doc. And I thought about his doc he did with Lance Armstrong where halfway through it, he realized Lance Armstrong had been lying to him for the first half of the production, and how he, in that doc, he is personally going, "I was affected by this." So I would say Alex Gibney is another person who's behind the camera, but you feel his presence in the docs he's making.

I definitely felt your presence in this. I loved having you as that guide figure here.

Providing a Platform

One of the things that I really appreciate about "We Need to Talk About Cosby" is that it gives the survivors space to not just tell their own stories, which is obviously incredibly important, but also to really participate and react to the clips and offer their observations just like all the other folks that you spoke with. Did you have to do a lot of convincing to get them to agree to speak with you? What were those early conversations like?

So our showrunner Katie King and our co-EP Geraldine Porras — and Geraldine I've known since "United Shades of America," she worked on that show with me for several years — they did a lot of the initial outreach to survivors. Geraldine really handled most of it. And so by the time they got to me, they had bought into the idea that like, "Look, we want you to tell your story, but we're going to ask other questions that aren't just about your personal contact with Bill Cosby. And, just to be clear, this doc is not just a doc about the assaults." When you watch "Surviving R. Kelly," you know he's a musician, but we're not really necessarily here for the music. You have to know he is a musician to understand how this all went down, but we're not here for that because, and understandably so, Dream Hampton was basically saying, "This is a crime in progress and we need your help catching the criminal." But with this, it was like we wanted them to understand we're really going to do extended sections talking about his career, that may not be something you want to be a part of. It's not going to be a strict, just the crime. So by the time they got to me, they had already understood that. Then, luckily, many if not all of them knew my work from "The United Shades of America," so there was a sense of like, "If somebody can pull this off, it's Kamau." They were just like, "I'm happy to meet you. I'm happy to talk to you." They were like, "Tell me about the Ku Klux Klan episode," which sort of opens the conversation in a more natural way.

The conversations went for, some went for an hour, some went for two hours, some went for over three hours because you really just want to be there with the person while they're going through it. And if you relax into the conversation, you'll find out things that you didn't know you were going to find interesting. So with Victoria Valentino, we didn't know that her son had died in a pool accident so shortly before she met Bill Cosby. And you don't necessarily need to know that to believe she was assaulted, but it does inform the story and present her as more than just the night she was assaulted. And then on top of that, she was a Playboy Playmate and a Playboy centerfold, so she's an expert about more things than just being assaulted by Bill Cosby. So with all the survivors where we could, we wanted to put them in there in ways where the first time you might meet them would be like, as an expert in their field about X, Y, and Z. And if you don't know, you just go, "That's interesting." And then when you hear their assault story, it is like, "I had no idea that person I'd be listening to was somebody who'd been assaulted by Bill Cosby."

A hundred percent. That worked really well.

"I didn't realize how much grooming had gone into this."

It's clear that Bill Cosby was a towering figure in your life for a long time. Were there aspects of his history that you learned while making this that you didn't know beforehand?

I didn't realize how much grooming had gone into this. I think even those of us who believe the women's stories like I do, and believe that they were sexually assaulted or raped, I think there's a way in which you, if you aren't reading the full articles — I really did a lot more work, I did a lot more research in the making of this than I had done before. If you just read the headlines or the first couple paragraphs of the article, you can sort of put this into 60 one night stands. The idea that like, "Rape is horrible, but these were 60 women who were at the green room after the show." Which is still not — you can't rape anybody, but you frame it like that. But then when you hear the stories, it's about how much work he did to stay connected to them, how much he promised them things, flying them around the country, being out of touch for months and coming back into touch and how at some point, some of these women in the course over the years were suddenly — one day they'd be like, "Oh my God, I realize what's happening now." And how long this went through their lives, how some of them started very young and then it wasn't until years later that they realized what was happening. And that way it connects to the "Surviving R. Kelly" story in a way that I don't think people really understood with Bill Cosby.

Separating Art From the Artist

In the last episode, you point out that over the last few years, audiences have had to contend with the idea of separating the art from the artist in a more direct way than ever. I was wondering if you could tell me more about how you approach that idea in your own viewing or listening habits. Do you have a "one size fits all" approach to this? Or is it like on an individual basis? How do you deal with such a big issue like that?

I think, let's be clear: We are all doing that all the time, we're just not aware that we're doing it. There are some artists that you won't mess with because you just don't like them. You're like, "I like that song, but that guy's an a**hole." Or, "I used to like that guy, but now his politics have gotten weird." You know what I mean? So we are doing that all the time. We are always defining ways to separate the art from the artist. Or, "I really like that song. His politics are weird, but I really like that song." So I think that we are constantly doing that. We only think of it when we're talking about people who've committed like heinous crimes. But there's any number of musicians that you've heard stories of them doing heinous things and you're still playing their music. I understand that about myself and I've understood it for a while. The thing that I also understand is like, I can listen to this song, but I can't expect go out into the world and go, "You know what song I really like?" and say it, and think everybody's going to be like, "Yes, that is just a good song." I know enough to know that some people are going to be like, "I can't listen to that song because of this." And I think the problem is we expect everybody to draw the line where we draw the lines or we act surprised. We're like, "Yo, you can't do it?" I think the problem is, we have to understand: We all do things in the privacy of our own home that we don't want to share with our coworkers at work. I think that if we understood that about all things, we would be better to understand that if you say, "My favorite song is," or, "My favorite TV show is this," and somebody goes, "Didn't the lead of that show rape somebody?" that you would understand, "Oh yes, that's true. I'm not taking that into account. I'm separating the art from the artist." And if you want to have that conversation with people, you can, or you can just not tell people what TV you're watching. [laughs] I think we've gotten to a place where letting people know what content you're taking in, you want that to be a part of your character building.

I'm curious if you think about the distinction between — like, somebody doing standup comedy? That's like a solo pursuit. Their art is a representation of their character in a certain way. And then if you, in that example you were just mentioning of the lead of a TV show raped somebody, there's an entire infrastructure that helped produce that television show. Even if it's the star of the show, it feels a little bit more like a group effort. I wonder if you think about that at all, in terms of like, "Ah, I can't listen to this music because this person produced it and were heavily involved in the creation, it feels more like the solo creation of this person," versus a movie directed by somebody who was accused of a terrible crime, and there's all these different artists that went into helping create that thing. Do you draw that distinction in your own viewing or listening habits at all?

I think I'm aware, because I work in this business, it's always a group effort. If you're a famous comedian standing in an arena, that's a group effort. So I think for me, it's like, I don't draw that distinction about ... I mean, there is content I will watch knowing that that person is an a**hole or that person has been accused of things, and in the privacy of my own home, I will take that in and I will reckon with that. I don't talk about it a lot, but I'm a fan of mixed martial arts. I'm a fan of the fighters of the UFC. Now, Dana White is a hardcore MAGA Trump guy. Trump is his friend. He loves Trump. Dana White, I believe, also doesn't pay his fighters enough. Tonight there's a huge UFC fight that's about to happen, and ESPN just raised the prices of the pay per views. Do I want to give more money to this thing? I don't have to agree with the politics of who owns everything, but he specifically is a big friend of Trump. And I feel like he should pay his fighters more. But then I go, "But if I pay for the pay per view, aren't I at least helping his fighters make some money?" But then I'm like, "But is that money going to the fighters?" That's the thing I'm having right now about a UFC fight tonight that I just want to turn on and watch Francis Ngannou and Ciryl Gane beat the hell out of each other. I haven't answered. I don't know yet. [laughs] That's where I sit right now. And none of that is about crime, I just want to be clear. But I'm saying that's a very low level example of what we're talking about. You look in the UFC, you see two guys fighting, it seems like it's two individuals fighting, but there's a whole infrastructure in place that you have to reckon with.

"Keep having the conversation."

If somebody were to have one takeaway after watching "We Need to Talk About Cosby," what would you hope that takeaway is?

That takeaway is keep having the conversation. If you watch it and you go, "All of that is bullshit. F*** that guy," I feel bad. Because I feel like there's enough in here to at least keep a conversation going. And by "f*** that guy," I mean f*** me, W. Kamau Bell. But if you watch it and there's things in it that are intriguing that you want to go Google, that you want to look up, I think you should watch it with people and have the conversation with people. I think that's one of the bad things about it not being [in person] at Sundance is that I would imagine conversations that spilled out into the streets and into the clubs and the bars would keep it going. But I hope that when it airs on Showtime that people find a way to be in community about it, because what the doc really wants is, and what I want and everybody who worked on the doc wants is, we need to create a safer environment for people who are saying they've been raped or sexually assaulted and we need to create better infrastructure so that it is less likely to happen, which is not that difficult to do. The thing I always say is when they built showbiz, they didn't start with the human resources department. Currently I think the human resources department is still not a prominent enough part of any business, but specifically Hollywood.

"We Need to Talk About Cosby" premieres on Showtime on January 30, 2022.