Why Jerry Lewis' The Day The Clown Cried Was Never Released

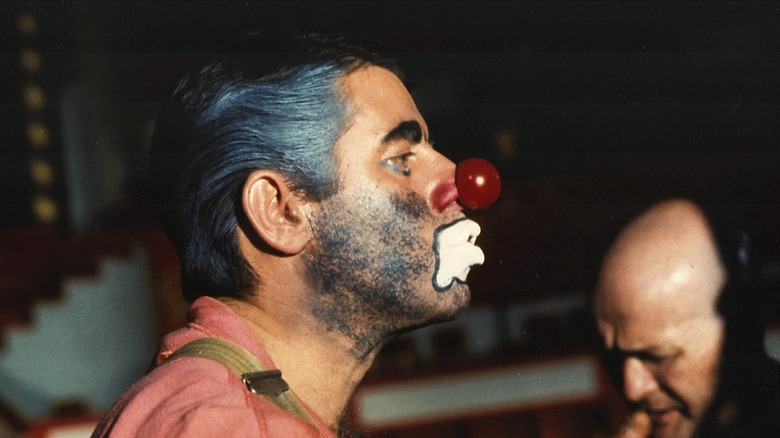

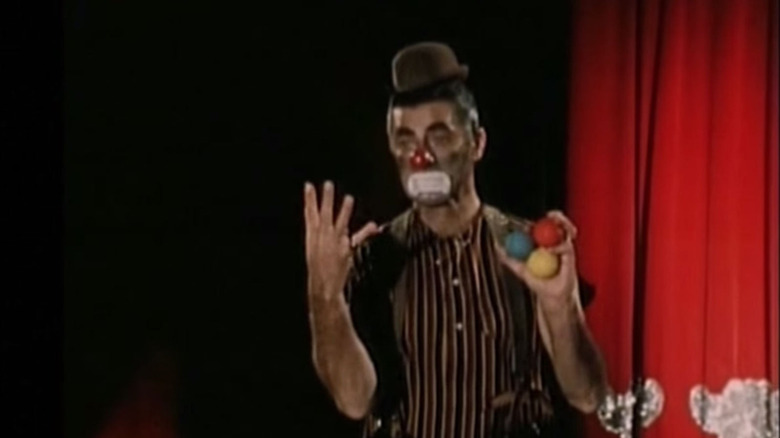

In the early '70s, Jerry Lewis made a Holocaust drama so controversial that it still provokes lively debate today, even though almost no-one on the planet has seen it. The film is "The Day the Clown Cried," the story of Helmut Doork, a third-rate German clown who finds himself in Auschwitz, where he is given the task of leading Jewish children to their deaths in the gas chambers.

Lewis, who rose to fame as part of a wildly popular comedy duo with Dean Martin, was one of America's biggest stars during his heyday. He directed several films too, including perhaps his best known movie, "The Nutty Professor." But Lewis was better known for his manic slapstick routines and silly voices than his dramatic chops. Whether people loved him or hated him, there was little doubt that he was a prodigious talent, but did he have the ability to make a film about such a devastating and sensitive subject? Especially with – *gasp in horror* – comedy involved?

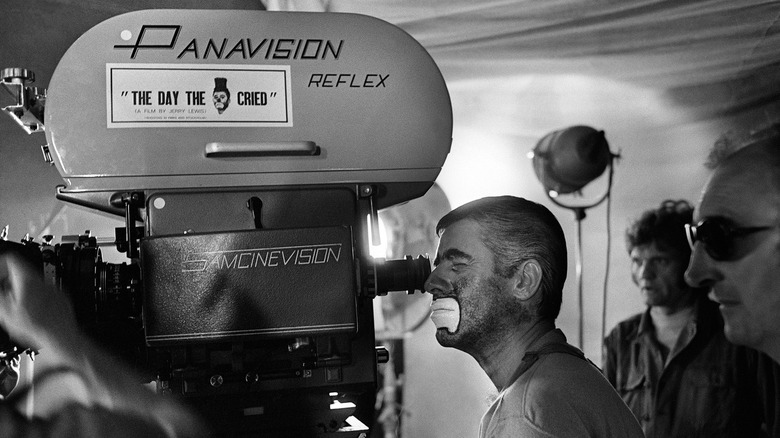

Unfortunately, we are still waiting to find out. The famously prickly actor and director passed away in 2017, having vowed during the intervening years that "The Day the Clown Cried" would never see the light of day. Nevertheless, a few years before his death, Lewis donated a partially complete version to the Library of Congress, on the condition that it would not be shown before 2024. But even without seeing the film, we know quite a bit about it.

How Did Jerry Lewis Get the Job?

Lewis was approached with the project in 1971 by producer Nat Wachsberger, who offered him the chance to direct and star in the picture with full financial backing. He wasn't the Belgian producer's original choice; other stars also better known for light entertainment were approached, including Milton Berle, Bobby Darin, and everyone's favorite Cockney chimney sweep, Dick van Dyke. They all declined, and next up was Jerry Lewis (via Mental Floss).

Lewis, a Jewish person himself, had reservations about his suitability for the part due to the harrowing subject matter. Nevertheless, after re-reading the script by Joan O'Brien and Charles Denton (which you can find online) he eventually signed up.

After filming preliminary footage in the ruins of the Auschwitz and Dachau concentration camps while also re-working the script, Lewis started shooting the film in Sweden in Spring 1972. The production was immediately beset by problems. There were issues with equipment and the money promised by Wachsberger failed to materialize. Lewis showed full commitment to the project, eating nothing but grapefruit for six weeks to lose 35 pounds for the role, and stumping up $2 million his own cash to complete the film after the producer "skipped town" (via The New York Times).

A tangle of contractual and legal issues followed, with the film deemed unreleasable without securing the rights from O'Brien. Worried about losing the film, Lewis took a rough cut while the studio kept the negative. Around that point, Lewis still seemed optimistic that his work would be completed, telling Dick Cavett that "The Day the Clown Cried" would premiere at Cannes. Yet the film was never released.

The Mystique of The Day the Clown Cried

"The Day the Clown Cried" has become one of the most famous "lost" films, a source of intrigue and the butt of many jokes for almost half a century now. There are many articles about it online, but much of its mystique stems from a snarky oral history in Spy Magazine from 1992 entitled "Jerry Goes to Death Camp."

Harry Shearer, the voice of Ned Flanders, Mr. Burns, and many other characters in "The Simpsons," is one of the few people to have laid eyes on the film. He told Spy:

"With most of these kinds of things, you find that the anticipation, or the concept, is better than the thing itself. But seeing this film was really awe-inspiring, in that you are rarely in the presence of a perfect object. This was a perfect object. This movie is so drastically wrong, its pathos and its comedy are so wildly misplaced, that you could not, in your fantasy of what it might be like, improve on what it really is. "Oh, My God!"—that's all you can say."

In the same article, screenwriter O'Brien claimed that Lewis had reworked the central character into someone more sympathetic and Chaplin-esque. She originally wrote Helmut Doork, the clown, as a far more selfish and reprehensible individual. While her character's motivations were ambiguous, Lewis's version offered Doork a redemption of sorts.

Joshua White, a director who screened a rough cut of the film in 1979, was a little more sympathetic:

"When I saw it, I felt for him [Lewis], because I could see him trying to clear the hypocrisy out of his life... Then to see this film that was so important to him and that was almost incompetent was just sad."

Praise for The Day the Clown Cried

In recent years, there have been voices coming out in defense of the film, or, at least, Lewis's decision to tackle the subject many years before the "Holocaust drama" became mainstream.

Bruce Handy, who wrote the original 1992 Spy piece, interviewed French film critic Jean-Michel Frodon for Vanity Fair, and he praised Lewis's work:

"I'm convinced it's a very good job. It's a very interesting and important film, very daring about both the issue, which of course is the Holocaust, but even beyond that as a story of a man who has dedicated his life to making people laugh and is questioning what it is to make people laugh. I think it is a very bitter film, and a disturbing film, and this is why it was so brutally dismissed by those people who saw it, or elements of it, including the writers of the script."

Frodon even went so far as to say "The Day the Clown Cried" was more honest about the Holocaust than a "crowd-pleaser" like "Schindler's List."

Elsewhere, speaking in "The Last Laugh," a documentary discussing whether the Holocaust could ever be a suitable topic for comedy, David Cross said that Lewis was "too ahead of his time" and added, "If he had waited 25 years, he'd be bounding over those seats grabbing his Oscar."

Cross was no doubt referring to Roberto Benigni jumping around on chairs to celebrate his "Life is Beautiful" triumph at the 71st Academy Awards. He may be right; while the prospect of a Holocaust drama by comedian Jerry Lewis was met with general distaste at the time, Benigni's similarly themed movie picked up a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, while almost everyone politely forgot about Robin Williams' mawkish "Jakob the Liar" a few years later.

Will We Ever See It and Do We Want To?

Lewis, who was reportedly a tetchy character at the best of times, faced decades of questions about "The Day the Clown Cried" from reporters and interviewers, all while veering between pride in his work and utter disappointment with the unfinished product. He was screwed over while making the film and harassed about it afterwards, so it's little wonder that he didn't want anyone to see it.

Was he the right man for the job at the time? It's impossible to say without seeing it, but Lewis certainly proved he had the acting ability in "The King of Comedy" ten years later. He was also an underrated director, beloved in France, and his solo projects were compared favorably to the later works of Luis Buñuel by Martin Scorsese. He also had staying power when he committed to something; his annual telethon raised $2.6 billion for the Muscular Dystrophy Association for 44 years, which ran long after he faced criticism for how the event portrayed sufferers of the condition.

If we ever get to see the film, it will be fascinating to see what Lewis managed to achieve years before "Schindler's List" brought the subject into the mainstream. The better modern Holocaust dramas keep the memory of the atrocity alive, which is especially important when a recent survey revealed that almost two thirds of adults between 18 and 39 in the US are unaware that 6 million people were murdered during the Holocaust.

Ultimately, the most intriguing question is: was "The Day the Clown Cried" the ghastly, misguided train wreck and vanity project that some have suggested, or the important, bitter piece of work described by Frodon? In two more years, we might just find out.