The Butterfly Effect's Original Ending Was Ridiculously Grim

The phrase "the butterfly effect" stems from the tenets of Chaos Theory, which we all think we know about because we saw "Jurassic Park." It is, as with all things pertaining to mathematical theory, far more complex than a charming grin from Jeff Goldblum. Actual chaos theory states that seemingly complex and chaotic arrangements of numbers will eventually reveal themselves to be discreetly patterned, and how small, seemingly random changes early in a mathematical structure can lead to larger, more dramatic changes much further along in the same structure. The butterfly effect — and this is taken from rudimentary internet research and not years studying mathematics — describes how a small change in one state of a deterministic, nonlinear system can result in large changes later on in the system. The phrase, coined by mathematician and meteorologist Edward Lorenz, comes from an axiom about how a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil can cause a tornado in Texas.

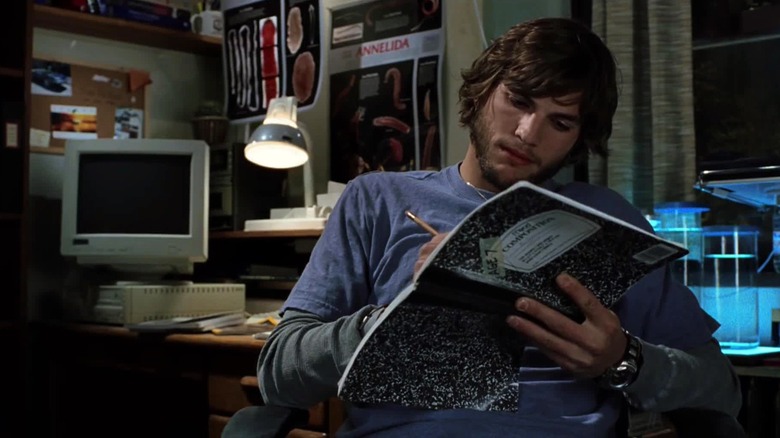

Eric Bress and J. Mackye Gruber, the writers and directors of the 2004 time travel thriller "The Butterfly Effect" with Ashton Kutcher only seem to vaguely grasp broader notions of chaos theory, but that hardly matters, as they were far more interested telling a bleak sci-fi story of trauma and the futility of healing efforts. The fineries of nonlinear dynamics and deterministic chaos were less vital to this story than the title might have you believe.

And yes, as that eye-grabbing headline so boldly states, the original ending for "The Butterfly Effect" was exceedingly grim and nihilistic, and that's after a film that includes many scenes of children in horrific danger.

The Time-Traveling Consciousness

In "The Butterfly Effect," Ashton Kutcher plays a young man named Evan who grew up suffering from memory blackouts. His memory blackouts coincide with horrendous traumas he suffered, including being strangled by his own father, accidentally killing two people with an explosive device, and being victimized by a child pornographer played by Eric Stoltz. It was not a rosy childhood. Throughout it all, however, Evan found solace in — and carried a torch for — his best friend Kayleigh (Amy Smart) who was coping with the same trauma on her own and never found Evan to be a potential romantic partner.

Oh, Evan also has a superpower: In college, Even learns that he can read his old childhood journals and psychically shunt his present-day consciousness back in time, placing it in his body during those aforementioned blackouts in his younger years. In so doing, he attempts to undo all his, and Kayleigh's, past childhood trauma. He is, however, a bit clumsy in his attempts, and for every problem he erases, he creates a new one, sometimes much, much worse for himself or for Kayleigh when he returns to present day.

By the film's end, Evan has learned that, for all his tinkering, it was his presence in Kaleigh's life that made her the most miserable, so he arranges a timeline wherein Kayleigh grows up without him, becoming far happier and more successful. Evan has to live with the fact that, by merely existing, he made his true love's life more miserable. It's a grim realization, but he gave up everything for the woman he loved, so it's satisfying.

The flinty messages of that ending were in line with the horror films and thrillers of the time, which were skewing darker and darker in the wake of 9/11. The late '90s saw playful, self-aware thrillers like "Scream" and "In the Mouth of Madness" and "Urban Legend." After 9/11, we began seeing films of torture and hopelessness like "Saw," "Hostel," and "Buried." "The Butterfly Effect" possessed some of that latter group's underlying nihilism.

That nihilism was even more pronounced in the director's cut.

I Don't Want to Be on This Planet Anymore

It's pretty harrowing to think that your involvement in another person's life is making both of your lives more miserable, but that dark setup, in the original cut of "The Butterfly Effect," leads to a noble sacrifice and a gentle catharsis. In the great scheme of romantic destiny, sometimes you find you're destined to stay apart, and Evan was able to make a sacrifice to his own personal happiness to assure the survival of another. Sad, perhaps, but dramatically satisfying.

But what if there was an ending to "The Butterfly Effect" where Evan's rejection of his one true love still led to a world of misery and pain? Remember that scene described earlier when Evan's father tried to strangle him. It turns out this was expanded in the film's director's cut. In a deleted subplot, we learned that both Evan's father and his grandfather possessed the same shunting-back-in-time superpower he has, and that Evan's father was trying to take him out of the timeline for his own reasons. In that same director's cut, we learned that Evan's mother has previously given birth to two stillborn siblings of Evan's, and that Evan was her own personal miracle. Given how much misery his life has caused others, however, Evan — while watching his own childbirth video — shunts his mind back into the body of his newborn self and — steel yourself — strangles himself to death with his own umbilical cord.

It's not just Evan's presence in Kayleigh's company that's causing her misery, but his very presence in the world. I don't know if Eric Bress and J. Mackye Gruber were fans of Edgar Allan Poe or Franz Kafka, but this is deeply depressive psychology at work. The world is worse off with you in it, and the best way forward is to remove yourself from the timeline completely. Enjoy your popcorn, fans of "That '70s Show." Additionally, it's implied that Evan's stillborn siblings also had his time-traveling abilities, and perhaps elected to do the same thing, implicating that the parents were also culpable in adding misery to the world in merely having children. The filmmakers weren't in any kind of mood for hope.

No One Wanted It

"The Butterfly Effect" wasn't received well, garnering mostly negative reviews; it currently holds a 33% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Although it earned back a enough of its small $13 million budget to warrant two sequels in 2006 and in 2009, both of which went straight to video (when such a thing carried with it a stigma), and neither of which has any kind of meaningful connection to the 2004 original.

At the time, however, few of the criticisms referred to the film's grimness or nihilism. "The Butterfly Effect" was horror-inflected, so the death and pain was just a natural part of the genre. And, indeed, being grim is no blow against any film in and of itself; David Fincher's "Seven" was released nine years before, and that film so pessimistic it becomes almost comical. The complaints about "The Butterfly Effect" had much more to do with its tone: It was partly a bleak horror thriller, but also a hip-talking teen drama about Getting the Girl™. Many critics also indicated that a comedic actor like Kutcher didn't have the chops to carry a heady film about trauma, child pornography, and despair.

Perhaps if "The Butterfly Effect" had stuck to its ultra-bleak ending, it would have, at the very least, stood out more.