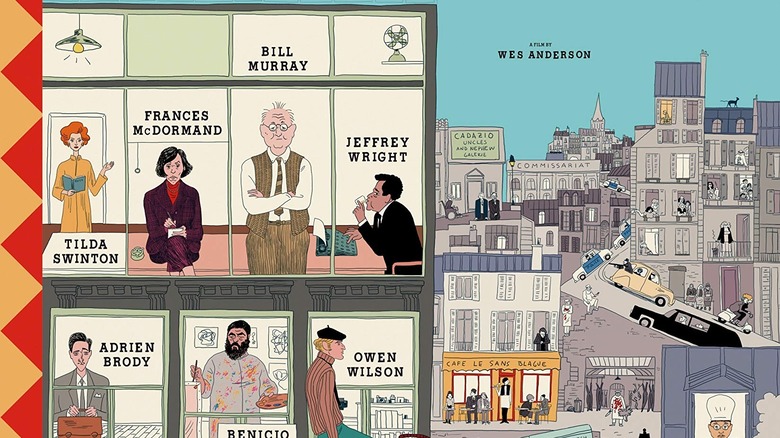

The French Dispatch Is Wes Anderson's Love Letter To The World Of Magazine Writers

It's evening on a Tuesday and the theatre is sparsely attended — a press screening, as most of these affairs are. At seven sharp, the lights fade and Wes Anderson bursts into the room with his latest issue, "The French Dispatch." The film is a magazine, disparate stories from different writers and different voices, each fading between black-and-white print and shocks of color where the photos or prose stand out.

Anderson, 52 now and showing his maturity but with a whimsical aesthetic that belies his age, assembles an issue from the top down. With the grace of a gifted raconteur, he carefully tells us everything we need to know about the editor of the magazine, Arthur Howitzer, Jr. (Bill Murray), before giving us a sampling of some of the best he has to offer. There's an easy charm to the stories, even those with uneasy moments. Bolstered by the success of his style in the past, Anderson — a star pitcher who has mastered delightful variations of a single trick pitch — is unapologetic about the nature of his storytelling. Almost as if he's laughing at us, daring us to care that none of the artifice of his films portray a reality we know, but the reality is reflected in the subtext of the stories themselves.

While this film doesn't reach the heights of his most restrained masterpiece, "Rushmore", "The French Dispatch" has much to offer.

In an interview with the legendary American publication, The New Yorker, Anderson speaks of his inspirations for "The French Dispatch" with his trademark intelligence and a soft voice. "I read an interview with Tom Stoppard once," he began, "where he said he began to realize — as people asked him over the years where the idea for one play or another came from — that it seems to have always been two different ideas for two different plays that he sort of smooshed together. It's never one idea. It's two. 'The French Dispatch' might be three."

The Articles

The movie Anderson brought to the theater is split largely in three, one for each of those ideas he spoke of. He brings them with an air of confidence that some might mistake for a poisonous fume, though deadly gas had never been so funny. Aside from the trappings of other stories here and there, there exist the frames with which to hang the structure of his omnibus. The first major epic he settles in to tell — through the voice of the redoubtable red-head and occasionally naked J.K.L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton) — is a tale of art and a romance between an inmate named Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio Del Toro) and his prison guard, Simone (Léa Seydoux), as they find truth in beauty and masterpieces in fresco. Naturally, anyone with talent like Rosenthaler's would find themselves exploited at the hands of a wretched soul like Julian Cadazio (Adrien Brody.) Along with his uncles (interpreted delightfully by Bob Balaban and Henry Winkler), Cadazio, through misadventure and misfortune, brings the avante garde world of Rosenthaler's art to the corn-planted plains of Kansas.

The second story speaks of revolution and a May/December romance between a young, charismatic student, Zeffirelli (Timothée Chalamet), and Lucinda Krementz (Frances McDormand), the reporter sent to cover him. As they grapple through their difficult feelings for each other, for the war raging beyond, and the misunderstandings between generations, a tragedy plays out. The dish served here is equal parts absurd and funny, tragic and introspective.

The third and final part is told through the typographic memory of Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright), as he relays his magazine article to a talk show host (Liev Schreiber). Sent on assignment to review the food of the legendary police chef Nescaffier (Stephen Park), Wright finds himself embroiled in a kidnapping case that has the beginnings of a Kurosawa-noir, but ends up in the illustrated pages of the magazine because the truth would be almost too much to be believed.

The Meaning

Ultimately, these thrilling tales offer windows into the soul of human connectivity, dressed in the laughs that only Anderson can deliver. Each joke feels framed in his patented center-framed style. Anderson himself once described the film as a confection, and a confection it is, sweet like cotton candy. Thankfully, the ideas don't quite waste away into nothing as a viewer plumbs below the surface, slowly descending into the deep like a 19th-century sea-diver in an overwrought helmet out of a Jules Verne novel.

At the open of the magazine, an obituary is promised and this coda fulfills the early promise, but not in the way each character (or the viewer) might suspect. Howitzer left strict instructions that, upon his death, the entire magazine would be destroyed and the morale of the surviving writers shot to pieces, as his namesake might subtly imply. But obituaries are for the living, and the writers of "The French Dispatch" eulogize their former employer in the only way they know how: with the luxuriant words of their trade, finding just the right phrases to sum up a life that was, if nothing else, workmanlike; dedicated to bringing the stories of Ennui-sur-Blase, France to the farms of Liberty, Kansas, USA.

Anderson understands so well the thing he's trying to accomplish here. We all have stories to tell, but few tell them so eloquently, with the skill and craft of a long-format magazine writer, leaving a reader hanging on each word like a rock climber along a sheer face, clutching for purchase and scrabbling for the next. The compulsively readable nature of a magazine, as each disparate story transitions into another, is something lost that might feel like a forgotten magic these days. As the lights come back up in the theater, and the reality of the world returns, Anderson proves that he has the ability to tell many different types of stories with that self-same skill. Whether or not these three stories add up to anything, though, might be best left to the audience.

The Denouement

As the theater emptied and the final notes of music played and Anderson's last credit rolled up, everyone is left pondering the meaning of the stories combined and I realized that "The French Dispatch" was a love letter. Not to the indomitability of the human spirit or the engines of empathy Roger Ebert spoke so eloquently about all those years ago, but to the long-format magazine writers themselves; to the long sentences that ended in just the right metaphor, bringing color to the black-and-white experience of the reader; to the illustrations that managed to encapsulate the mood and emotion of the story, wedged between towering columns of ink; to the well-managed juxtaposition of disparate stories placed side-by-side by the keen judgement of an editor who knows just how to keep the reader riveted.

Anderson delivers this love letter with aplomb, but he might find the audience for this film to be so few it might not have been worth his while, for the age of the magazine passes like elves to the Undying Lands.

For those of us who care, though, it's to our fortune that Anderson persists.