Titane Director Julia Ducournau On Crafting Her Disturbing, Violent Love Story [Interview]

How do you talk about a movie like "Titane"? Julia Ducournau's gruesome body-horror follow-up to her 2016 breakout film "Raw," has been the center of shocked pearl-clutching and critical raves alike, winning the prestigious Palme d'Or out of the Cannes Film Festival. But despite its reptation for gory shocks, "Titane" is a hard film to put in a box. It's a body horror thriller, yes, but it's also a family drama, a comedy, and unexpectedly, a strange kind of romance. But to Ducournau, those labels don't matter.

"I do use the grammar of body horror for sure. I also use the grammar of other typologies, like comedy, thriller, drama, obviously," Ducournau told me in an interview following the New York Film Festival screening of "Titane." "But for me, you have to understand that this goes all together, it's a whole, you see? I'm just trying to build my own language."

It's easy for Ducournau to talk about "Titane," a film that baffled many an audience member (including this writer, who sat in shocked silence for a few minutes after the credits rolled). Lounging back in the hotel room chair in a round of press interviews for "Titane," Ducournau gives off the impression that everything about "Titane," to her at least, is matter-of-fact. Of course this movie about a serial killer who gets impregnated by a machine is actually about love, why would you believe any different? her piercing eyes seem to demand of me. Ducournau has been living with the film for at least five years, after all, having conceived of the idea during the post-production of "Raw."

"I set myself the challenge to talk about love, and to put ... love at the center of my work," Ducournau says. "And try to somehow communicate this idea that I have of a love that is unconditional and absolute, that somehow in full acceptance of yourself, and of the other one."

That's right, "Titane" is indeed a love story, Ducournau confirms. But it's still a wildly subversive love story that juggles ideas about motherhood, fatherhood, gender, and sexuality, all the while engaging in some of the most brutal and transgressive violence seen onscreen this year. Here's my full chat with Ducournau, in which we speak about the male gaze, the inherent violence of the female body, and "feeling the feels."

"It's really putting love at the center of my work."

How did you conceive of "Titane," and the wild story that it has?

It's a long process, as you can imagine, of basically trying to kind of connect the dots between ideas, or images, or desires, fears as well, themes. It's never quite the spark moment I think that people want to believe, I think it's really a process over many months. That, for me, stands also in "Raw," somehow, in the making of "Raw," and in the post production of "Raw," because I started thinking about "Titane" during the post of "Raw." Just because at one point, I need to think about other stories, and to kind of somehow find the continuity in between my films, and to go another direction and when I'm still doing the previous one.

It's a vital need for my brain, if you wish, because usually when you're in post, it means that you've been with the film for at least four years already, because I write them, and I need some new directions. So, that's when I started thinking about "Titane," knowing that I set myself the challenge to talk about love, and to put... It's not really "talk about love," because it's not talking about it. It's really putting love at the center of my work. And try to somehow communicate this idea that I have of a love that is unconditional and absolute, that somehow in full acceptance of yourself, and of the other one. In a form of dialogue between the selves, if you wish, and that is something that is, to me, more of a becoming than of a state. I wanted somehow to portray and to make you feel that becoming, hence the very transformative arc of the film and of the characters.

Like "Raw" before it, "Titane" also uses the monstrous to examine ideas of sexuality, and identity, and like you said, becoming. Can you explain why it was cars specifically, and why those sort of mechanical elements were important to the story you wanted to tell with Alexia's journey towards finding human connection and that unconditional love?

Well, there are many things. I think that metal stands for many things there. Talking about cars, for me, I had the idea of the ending of the film very early on. I knew how I wanted to leave my audience, I knew how I wanted to aim towards that very essential love between my characters. That birth of a new humanity, of a new world, somehow, that is stronger than the one we have left behind. Knowing how it ends, and I'm not going to detail it here, obviously, because I don't want to make any spoilers. But you see how I walked my way back to the beginning, and to the genesis of that ending, and that led me to cars. I think, for me, cars, it works a lot as a symbol. A symbol for patriarchy, but also a symbol for the way my character takes over that patriarchy, and takes the car as an accomplice in the expression of her own desire of her own narrative.

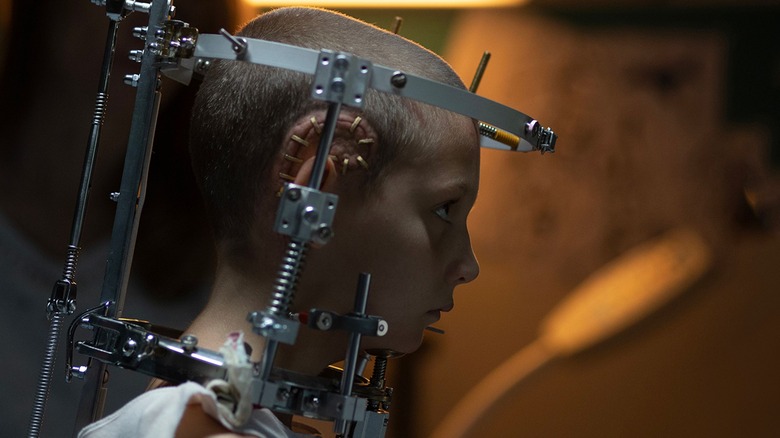

That indeed can be seen as monstrous, but also that is only hers at one point in this level. So, it worked like this. Also, there is a transformation of metal in my film, that goes from a dead material, that is cold and that actually reflects the coldness and the dead piece that she has in her head, as a form of, let's say, a hole in her humanity, somehow. But at the same time, when you get towards the end, metal starts to be more alive, and more lively. So, in a way, metal has its own redemption arc as well throughout the film, because you see that at the end, it's actually very much alive. So, for all these reasons that for me it was something that was interesting to dig in. The irony, obviously, being that the less human her body appears throughout the film, the more she actually humanizes. Which was, for me, again, a form of narrative irony that I wanted to dig in.

"The idea was, again, to make her reclaim the written narrative."

I think there's something interesting about how you're saying that cars were a creation of man that's transformed through this woman into something newer, and more loving, and less cold. I think that's such a unique way at how to examine humanity.

Thank you.

So, the film upends the male gaze in its first scenes with the car show, leading to the first of many violent murders. Why did you stage the first reveal that Alexia is a serial killer this way, through that sort of objectification, and then turning her into the victim, and then turning out that she is actually the culprit?

Well, it's all about shedding the layers of what we understand as gender, and the social construct and expectations that go around and with [it]. So, basically, in the oner that I do in the car show, I really wanted it to be a oner to really fill the evolution of the gaze on my character. So, basically, at the beginning of it, I try to mimic a male gaze that would objectify women and cars exactly at the same level. The sentence of the security guard says, he says, "Don't touch it, touch with the eyes," but that could apply for a car as well. The moment we get on her, and the way she actually dances with the car, and not only against it, the idea was, again, to make her reclaim the written narrative.

By looking through the lens of the camera many times, and by smiling at the audience, and actually enjoying what she's doing, it's a way to reverse the gaze by saying, "No, you're not looking at me, I'm looking at you. So now, I'm the main character, and I'm in control of that narrative." So, that was very important for me at this level. But yet, I mean, it's still in the realm of very strong gender stereotypes that are the very luscious dancers, erotic dancers, and all that. After that, there is something that's somehow through the stereotypes that go with the car show. It would be easy to think that she could be the victim of someone that was ill-fated, and stuff like that. That's, again, what I'm trying to make you think at this moment. For the first murder — which is actually a very ambiguous one, because the guy actually assaults her — she kills him both in retaliation for that assault, but also because she's a psychopath. So, normally, if this would happen, someone assaults you, you freeze.

You freeze in fear, in disbelief, and in the very conscious idea that is — I think is imposed as a social construct — that, as a woman, you're a designated victim. So, I think the reason why she manages to retaliate is not because she's better than us, certainly not; it's because she's a psychopath, and she can, because she doesn't feel the fear that we feel. All right, so again, trying to shed another layer on this social construct, you need to shed it completely. Also, what I wanted to do here is to show that a female character that was violent with no justification for it. Which is also going against this thing that we are designated victims, I don't want to give a psychoanalyzation of this. I don't want to explain it, she's just completely cold inside, and she is a dangerous character.

"It is really talking about this idea that we can have a new world that can be loved, even though it's monstrous."

I think so many genre films are about violence against the female body, but I feel like "Titane" is about the inherent violence of the female body. Especially in Alexia's actual metal body, as it grows increasingly more metallic. Also, the pregnancy itself, and how there's so many horrors that can come of pregnancy.

Yeah, that's true. I mean, I often say that it's absolutely not a film about motherhood. I think, for all that matter, it's more a movie about fatherhood. But because we have this male character who somehow cannot keep on living without being a father, who craved that so much, that he's ready to invent that fantasy where he's still a father, and who's lost with that. On the other side, you have this female character who's pregnant, but who does not want to be pregnant, who does not want to be a mother, and who indeed explores or discovers her pregnancy in pain, and in horror, somehow.

So, again, this, against all expectations you could have when we're talking about fatherhood or motherhood, trying to reverse that thing, and to show that it's not as binary as we think it is. Also, again, to portray pregnancy [as something] that is not the best year of your life, or that is not bliss, necessarily. It's painful as well, whether she's actually monstrous or not, or whether she's a psychopath or not, no matter... But it can be also a moment that is hard to cope with, very much, and making you feel horrified with your body as well, and it doesn't have to be bliss. It's okay to see something, or to what you feel that it's actually pretty painful or hard for yourself. Again, trying to debunk this social injunction that you have to really enjoy your pregnancy as a woman.

So, your film has been labeled a body horror film, as had "Raw." What do you feel about the term body horror? Do you think it applies to "Titane"?

Yeah, I think so. I don't think it's a body horror film all through, but I do use the grammar of body horror for sure. I also use the grammar of other typologies, like comedy, thriller, drama, obviously. People talk less about that, because obviously, sex, it's less graphic. I think that maybe the most disturbing parts of the film are linked to the body horror part. But for me, you have to understand that this goes all together, it's a whole, you see? I'm just trying to build my own language by using the grammars of diverse typology of films, especially when you're trying to kind of want to tackle the boundaries of humanity, and try to broaden the spectrum. I need to make you "feel the feels," as a director, I want you to feel like very broad spectrum of emotions towards my character, and also towards the film, obviously. So, that's how I like to play with the codes of all these typologies of film, and I'd like to divert them, to disrupt them, and somehow digest them in order to build the language that is the one of the film.

Kind of in the way how the machine and Alexia come together to build and digest something new as well?

Yeah, somehow, I mean, at the end, it is really talking about this idea that we can have a new world that can be loved, even though it's monstrous. That can be stronger, even though it's monstrous. That monstrosity somehow is not seen as a negative thing, and that is something that can be ... that can deserve that, and deserve the love that he gives at the end.

"Titane" is playing in select theaters now.