Worth Screenwriter Max Borenstein Wrote The Script Long Before His MonsterVerse Days [Interview]

Screenwriter Max Borenstein wrote "Worth" 14 years ago. Since then, he's become known as one of the brains behind Legendary's MonsterVerse, including the most recent addition, "Godzilla vs. Kong." Although his most famous work features monsters going at it, it was more dramatic work that helped launch his screenwriting career.

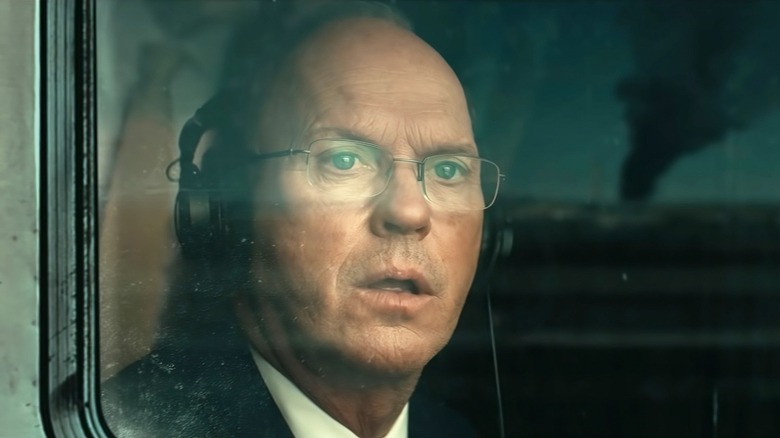

Borenstein wrote a Jimmi Hendrix biopic, for example, and has been waiting a long time to see his latest project, "Worth," come to fruition. The Netflix drama tells the true story of lawyer Kenneth Feinberg (Michael Keaton) attempting to put a price on the cost of life following 9/11. It's a challenging piece, for obvious reasons, and Borenstein recently told us about it in an interview covering the film's journey to screen.

When did you first read Feinberg's book? How'd you become familiar with his story?

No, I didn't know anything about the story until, I mean, obviously we were all affected, if we lived through it, deeply by 9/11, but this particular sort of aspect of the larger story, I wasn't familiar with the part from just in passing in a couple of articles. One of my fellow producers on the movie had become familiar with the book, the memoir by Ken Feinberg and had shared it with me. I read it and was fascinated. I was not quite sure how to tackle it as a story because it's such a complicated, it's such a sort of difficult subject matter even now, but at the time, it was much rawer. It was only six years or so after 9/11 and also very kind of procedural and difficult to dramatize, just because of the scope of the bureaucratic process that's at the heart of the story. There's this emotional core, but at the same time, it's a very bureaucratic process that Ken goes through.

I was fascinated by it, but I wasn't quite sure what to do with it. And it was during the writers' strike, and I was a young writer and had just done a few things and was getting some work doing rewrites on horror movies and action movies and things like that, the kind of work that you could get those days when you were very brand new. And then the strike came, and I was looking for something that was going to be something I could really sink my teeth into and just write on my own while I had all that time on my hands between picketing and whatnot.

I flew to DC and met with Ken. In meeting with him, that was the conversation that unlocked what ultimately became the emotional center of the movie, which allowed me to go beyond what was the bureaucratic surface of it and feel how that journey for him was a stand in for, I think, a shared experience that a lot of Americans who were not directly impacted by 911 in terms of losing lives of loved ones, but felt this deep connection emotionally to the story and a desire to involve themselves and somehow help.

When you're telling a story of this importance, when is dramatization appropriate and when is it inappropriate?

Yeah, I think it's always a fine line and it's certainly such a sensitive topic that it was very important for us not to fictionalize in ways that would betray what you'd call the capital T truth of what happened. Obviously, at the same time, we're not making a documentary and we're not trying to specifically characterize too many of the individual family members. We were compositing. A lot of the other victims and families that we hear are sort of composited versions of people. Many of the quotes that we use in the film, like the things people say, are taken with permission directly from anonymous quotes that Ken published in his memoir.

We were trying as much as possible to honor the true stories without exploiting anyone. While it's important to take a process that took years and was insanely complicated because it's government bureaucracy and streamline it down into a dramatic movie that requires a certain amount of simplification, we were trying wherever possible to simplify in ways that that weren't lies if that makes sense, that didn't make it feel fake in terms of its drama so that the simplifications serve the underlying truth of the emotional story and of the facts without necessarily having to show every single fact that took place because that would take a Ken Burns documentary.

"Not a Hero, Nor is He a Villain."

Obviously Feinberg is our protagonist, but how important was it for you to also make this an ensemble piece?

It was important. I think he's a protagonist in a sense, but he's not a hero nor is he a villain. He's our way into the story, as much as he's a uniquely qualified individual for this particular task in so far as he's, at that point was one of the most prominent lawyers in the country who had been the special master on various different tasks, like this distributing money in cases and all that.

He was one of the handful of go-to guys for a job like this. This job had never happened before. Never been nothing like it, and there probably never will be again. Even though he was unique in that sense, in the emotional sense, he's actually kind of an every man. He was the American who didn't lose anyone personal to him in 9/11, but who was deeply impacted emotionally as so many of us were, all of us arguably were, and wanted like so many of us did to in some way try to help, try to do what he could to make a difference.

He, in his own words, would admit that he wasn't perfect in his efforts to do so, that he was fumbling and flailing and screwed up at times. What I find inspiring about his story is the extent to which he was able to ultimately learn from his mistakes and adjust. But even then, what he was doing was not saving lives from a burning building. He's not a hero, but what he was doing was in the job that he had to do, as a government functionary. I think he was doing his best to bring humanity and empathy to the task ultimately, once he kind of got out of his own way.

The fact that someone working for the government can do something and that the government can actually serve this function of being empathetic to its citizens and giving a hand to help people move on after an incomprehensible tragedy like that, that's what I find heroic and inspiring, especially now in a moment where the discourse surrounding government has become so cynical, and it feels frequently like the government is not trusted to be in a position to do its primary function, which is help its citizens and civilians live better lives.

In your meeting with Ken Feinberg, what else did you learn from him?

Well, he told me the story of a family that became kind of like one of the key stories in the film that we externalized it somewhat to get it away from too close a resemblance to the actual family that it was based on. But there's truth at the core, which is that he told me his story that he hadn't published anything about this at the time. Since then he's been talking about it, but this family where the husband had died and the wife was grieving and didn't want to accept any money from the fund out of a matter of principle due to the fact that she didn't want to make blood money off of her husband's death. He was trying to persuade her to do it because they had this money to at least help.

I think for Ken, in a way I think that is very relatable, just wanted to do something and was frustrated that he couldn't do more. Then, he got a phone call from a lawyer representing the mistress of the decedent. There was this other family that also wanted to be compensated. It was an emotional and heartbreaking thing, just from a human level of Ken holding this kind of secret and having to look at the sort of flaws, the humanity, if nothing else, of the people who died. It's not simply, as we all know, 3,000 saints died in the tower. They were human beings, and that's what's really most tragic and most relatable about it.

I think the reason that sort of struck me in the moment was that this was much closer to the event. At the time, we went from a moment of this national tragedy that everyone was impacted by and felt emotionally connected to, and then like so much else in our lives, it became politicized. And so, it came to sort of represent things and the victims of these facts who were these human beings became used as martyrs by all sides in the political spectrum.

I think to me, that was a moment where it was clear that the martyrdom was erased, and it was clear that this wasn't a political thing. It was a human drama and a human question that was messy and uncomfortable and therefore also rich and beautiful, and I think relatable. So rather than being some very simplistic political movie, it actually was able to get into the messiness of life in a way that I thought could actually be great drama and more moving as a result.

As you said earlier, this is something you wrote during the writer's strike to just really sink your teeth into. Was that around the time you wrote Jimmy Hendrix movie too?

Yeah. I wrote that shortly thereafter. So this film I wrote during the strike, and then immediately after I... it's funny, my agent at the time, who was wonderful, but I didn't tell him I was writing it just on spec. I didn't get paid to write it or anything, but I didn't tell him because it felt like the third rail to make a movie relating to 9/11 in any way. It was the least commercial thing you could possibly do. He was probably right, because it's 12 years for us to even make it, but it was something that I felt deeply and it was well received at the time and wound up on The Black List.

Ultimately, it was a lovely door opener for me and my career. Strangely, it led to me getting hired by Legendary, because I think it was just a script people responded to there. I think if you read a drama, then you think, well, this person can write now let's give him a giant monster movie or something like that. So, it's funny, it's then four Godzilla movies later, finally this movie is coming out.

This business is strange and not especially conducive to making serious dramas anymore. I think that the ones that are worthy and where there's a lot of passion behind them, they do stand the test of time. And in this case, it's thrilling to finally see it making its way out into the world.

"It Would Be Amazing."

Right. After your time in the Monsterverse, too, people can see another side of you as a writer, too.

Yeah, definitely. Right now I'm making a show for HBO [a series chronicling the Los Angeles Lakers]. It is dramatic, but it's also really fun and funny and irreverent. I loved the monster movie side, but this will add like an extra another layer.

[Producer] Adam McKay is such a basketball history nerd.

He is.

How intense was the research for that show?

It's extraordinary. It will be the most heavily researched sports show or movie or whatever. There haven't been that many sports shows, to be honest. There are some, but it's as heavily researched as if you were doing something about Watergate or World War II. It's extraordinarily heavily researched, but we're not presuming to do a documentary because it's light-hearted material in a sense. It's basketball, and they're real people and we're treating all of that respectfully, but at the same time, we're having fun like Adam does in his films with the line between the reality and a heightened version. We're pretty open about it. So it's very much based on and inspired by the true story, but while still having fun in certain places tonally.

It's the things that are the craziest are all the truest. That's the important thing. We're taking liberties in small ways, what people see and say behind closed doors, but in terms of the big stuff that happens, we have receipts, and we're going to exciting fun stuff.

As for the MonsterVerse, do you think one of those movies could ever be done without humans and focus solely on Kong and/or Godzilla?

I do think it could be done. I was thinking about the same thing. I think it would be amazing, actually. I'm hoping that at some point in the next, given the success of that recent film, whatever phase that Legendary decides to do, that we see some of that because I think it would be pretty cool. I think it is possible. I think it'd be very ambitious, but it would feel ambitious in that sort of "Mad Max: Fury Road" way. I think it's totally possible to do that with the minimal amount of human character and you really characterize the creatures.