Movies Like Interstellar That Are Definitely Worth Watching

"Interstellar" is the closest thing to a classic science fiction movie that Christopher Nolan' has made so far, blending hard sci-fi tropes with an earnest exploration of humanity's drive to survive. For science fiction fans, it's instantly familiar stuff. Nolan's storytelling doesn't always land as powerfully as the movie's visual effects, but "Interstellar" still works as a thoughtful, understated love-letter to the stories that built the science fiction genre.

Stripped to its basics, "Interstellar" spins a time-tangled tale about how love intermingles with science to save humanity. Joseph Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) sacrifices himself to the eldritch currents of space and time in a last-ditch effort to find a method by which humanity can leave the climate-ravaged Earth and start over. In the end, "Interstellar" is not about what Cooper does to save the world, but what his love and desperation inspires. Cooper eventually closes the time loop he's caught within, leaving his daughter to finish what he started.

It's heady stuff, and Nolan's awkwardness when it comes to believable human emotion occasionally makes the plot stumble. But any weaknesses in "Interstellar" are shored up by its astounding visual effects and its insistence on scientific fidelity. The result is earnest, timeless, and beautiful. If you want to get even more out of Nolan's bare-hearted blockbuster, though, check out these films, which deal with many of the same themes and draw from similar inspirations.

The Right Stuff

Christopher Nolan screened "The Right Stuff" for his production crew before filming "Interstellar," and he considers it a nearly perfect film. It's also an excellent touchstone for fans looking to understand the emotional drive behind "Interstellar." Clocking in at over three hours, the 1983 adaptation of Tom Wolfe's non-fiction exploration of the astronaut program asks for a lot from its audience, but rewards audiences with some of the finest aerial footage in film history.

"Interstellar" also offers a passionate look at the daredevil mindset of pilots who first challenged space. While Tom Wolfe's thick, journalistic prose balanced the real-life characters with the danger they faced, the movie makes those risks its primary focus. It's a movie that bends the truth, and helped make a celebrity out of Chuck Yeager while underselling the achievements of John Glenn and the crew of the Mercury Seven.

Still, the combination of humanity and unmatched technological drive makes "The Right Stuff" a must-watch for science-fiction fans. Between the unbridled machismo is the story of our species itself. As both "Interstellar" and "The Right Stuff" prove, when faced with a dangerous riddle, humanity will not only find the answer. We'll do it with style.

2001: A Space Odyssey

It's hard to add Stanley Kubrick's science fiction masterpiece to this list without feeling like it's too obvious. Surely everyone's seen this movie. It's a go-to source for both homage and cheap parody. But "2001: A Space Odyssey" earned its place in history for a reason. The film treats space with the beauty and the terror it deserves, and its oddly hopeful ending pairs well with the optimism intrinsic to "Interstellar."

Kubrick worked with science-fiction author Arthur C. Clarke to create a story that veils clarity in metaphor and silence, carried by the riddle of the monolith and stunning visual effects and sets. Recreating our galaxy in ways both mysterious and familiar, Kubrick frames Jupiter's moons like isolated gods, bringing with them wonderment and despair. The shots of Frank Poole jogging in a centrifuge-powered loop within the Discovery spacecraft are understated, while an earlier shot makes a stewardesses' mundane behavior into magic. In "2001," life in space feels natural, not action-packed, building a contrast that gives the movie its acid-trip reputation.

The trippy climax plays on Clarke's specialties, raising a wordless but profound series of questions about what's next for our species. Like Clarke's earlier novel, "Childhood's End," "2001: A Space Odyssey" wonders how humanity might be shaped by the inexplicable. The ending may be confusing, but its hopeful notes regarding our rebirth in the womb of space ring clear.

Solaris

Stanislaw Lem's novel can be as hard to describe as the sentient ocean it depicts: "Solaris" depends on who's interacting with it. The Polish novel lost some of its idiomatic themes when translated to English, and all three film adaptations further dilute its message. As a result, Lem was frustrated with every iteration of the story beyond the original, although both Steven Soderbergh and Andrei Tarkovksy's adaptations converge on the same point Nolan rediscovers in "Interstellar": Space is humanity's darkest mirror, and the last and most perilous place we can go to find ourselves.

While Soderbergh's film is worth watching, Tarkovsky's 1972 version of "Solaris" remains supreme. Although Tarkovsky wasn't satisfied with his film, he came close to giving his sci-fi lament the depth it needed. Solaris cannot be humanized, and it can't be understood in any normal way. But it can be remembered or dreamed, and the impact that has on a human mind can rearrange a person down to their soul. It's this inhuman touch that's tearing apart the residents of Solaris Station when Kris Kelvin arrives, and his human mind isn't up to the task of changing the inevitable. And yet, there may be other ways to coexist.

Tarkovsky's "Solaris" is overwhelmingly contemplative and its themes are blurry, but it does give clues on how to follow its threads. Film School Rejects has a useful guide on how "Solaris" frames memory, with all its loneliness, in contrast to the actual truth. "Interstellar" draws from the same timeless ocean as "Solaris," but injects hope into its story with warmer cinematography and pure human emotion.

Silent Running

Released in 1972 in the shadow of both "Solaris" and "2001: A Space Odyssey," "Silent Running" is often overlooked. It's easy to be driven away by its heavy-handed environmentalism, and it's not as scientifically accurate as its predecessors. Where "Silent Running" thrives, however, is in reminding the audience how to love the world around us. The emotional toll the film takes on viewers willing to give it a chance is what makes it special.

Lonely and elegiac, "Silent Running" pins its story on Bruce Dern's biologist, Freeman Lowell. After Earth has been drained of nature, corporations have built small space arks to maintain some of our forests and fauna. But the corporations cut funding for these refuges during the film, driving Lowell to rebellion. His protest turns violent, and his victory is bittersweet. It's on-the-nose stuff, about as subtle as a brick-flavored martini. But the earnest way Dern pleads for the audience to not forget what nurtured us tugs at the soul.

"Silent Running" also lays the foundation for one charming "Interstellar" sub-plot. Nolan's robots, CASE and TARS, can trace their lineage back to the three service droids helping Lowell maintain his forest. Just as TARS' dry loyalty and pre-programmed humor gradually make him into something more than a mere appliance, the robots Huey, Dewey, and Louie's sacrifices make them part of the film's human experience. By the end, it's impossible to not empathize with their plight.

Sunshine

Deliberately bleak and trying to do too much in its not quite two-hour timeframe, Danny Boyle's 2007 film "Sunshine" is an interesting counterpoint to "Interstellar." Though critics were right to be underwhelmed with the exhausted serial killer tropes that weigh down its final act, "Sunshine" works best when it's dealing with the horrifying implications of its dying sun. Though much of the movie's science is pegged to fairly plausible standards, the film engages in some big, plot-necessary fibs. Critiquing the inaccuracies isn't useful, though; more than anything else, that scientific flair gives the movie's excellent cast something concrete to build on while facing the impossible.

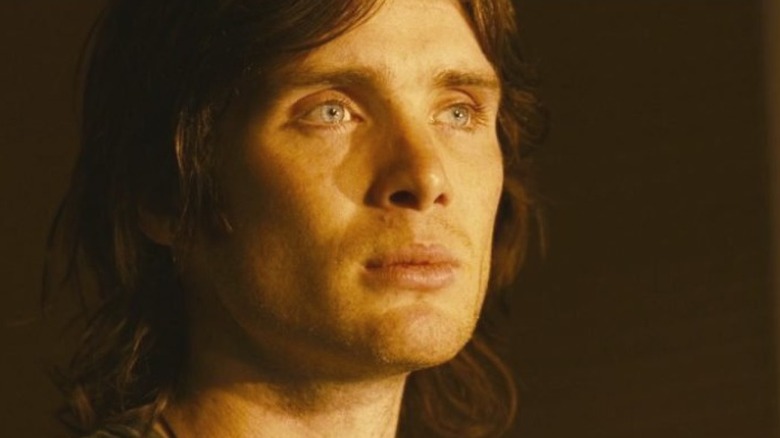

Almost 15 years after release, the "Sunshine" cast is a selling point all its own. Although Cillian Murphy was already a Boyle regular, watching performances from Chris Evans, Mark Strong, Hiroyuki Sanada, and Benedict Wong before they regularly starred in summer blockbusters is a treat. Thematically, "Solaris" is the closest predecessor to "Sunshine," with a voiceless, godlike star burning through every desperate act, but the movie's visuals and its characters' struggles to survive against the crushing void of space make it a good companion piece to "Interstellar."

Written by Alex Garland at the beginning of his career, this film is also a great transition piece for Nolan fans who want to try out more science fiction. "Sunshine" may not be the strongest film on this list, but it's still a good time.

The Martian

Another easy pick, Ridley Scott's 2015 adaptation of Andy Weir's debut novel goes for the hardest science it can without making the audience's eyes glaze over. "The Martian" thrives on the same irrepressible humanity that fuels "The Right Stuff," yet somehow Mark Watney's plight feels more realistic and empathetic, despite being purely fiction. Ridley's cinematographer, Dariusz Wolski, with the aid of both some stunning production design and also NASA itself, turns a Jordan valley into a vision of Mars that passes without question, pulling the audience into the story of a stranded astronaut.

Watney's fight to survive and his dry, often absurdist humor make the audience instinctively root and weep for him. It's a meme that rescuing Matt Damon gets more expensive in each subsequent film, but Damon's warm and approachable take on Weir's good-humored botanist makes him worth the cost. If "The Martian" had been released a few years earlier or later, it would've become an even bigger science-fiction touchstone. As it is, NASA's enduring love for the movie will keep it alive alongside "Interstellar" for decades to come.

Armageddon

No one will ever claim that Michael Bay's "Armageddon" has any scientific accuracy — even the movie's star, Ben Affleck, has problems with the movie's logic. Yet the film, with its comfortable Baysplosion cinematic palette and usual frenetic action, still manages to show off the beauty and terror of space. Michael Bay received permission to film at the Kennedy Space Center, making NASA's space shuttle as much of a star as Bruce Willis and Steve Buscemi. That shuttle goes on to carry most of what we may liberally call a plot, and the sight of its familiar silhouette, bright against the deep space black, is guaranteed to stir the imagination.

The story may be a mess, but buried somewhere inside of "Armageddon" are themes similar to those in "Interstellar." In "Armageddon," space is a mystery not easily tamed, while love can shift almost any mortal odds. That makes "Armageddon" one of Michael Bay's oh-so-slightly more thoughtful films, one that offers up almost touching moments of romance and familial love before things explode. "Armageddon" may not be high art, and it may have all the accuracy of a blindfolded archer after a six-pack of beer, but it remains a genuine joy to watch.

Moon

"Moon" is an intriguing take on the loneliness that permeates any number of science fiction films, tying that sensation to a literal identity crisis. It's a little like "Solaris," and has many overt homages to "Silent Running," a connection director Duncan Jones has discussed in interviews. But while "Moon" resembles other deep space adventures and plays with the same emotions those other ventures bring up, it also explores some real questions about how humanity could live long-term on the lunar surface.

For science fiction junkies who love a little truth in their movies, the helium-mining operation that Sam Rockwell's character oversees is based out of a bunker made from moon-produced materials. That's a real world concept that astrophysicists and geologists were already discussing when Jones introduced his film to NASA, at the organization's request. Mooncrete, also labeled in some scientific texts as "lunarcrete," is a slice of grimy futurism that makes "Moon" feel all the more relevant. Sam Rockwell's blue collar doggedness is an equally sturdy counterpart to McConaughey's trim farmer pretensions in "Interstellar." Meanwhile, Kevin Spacey's bodiless presence in the film can, thankfully, be ignored.

The Black Hole

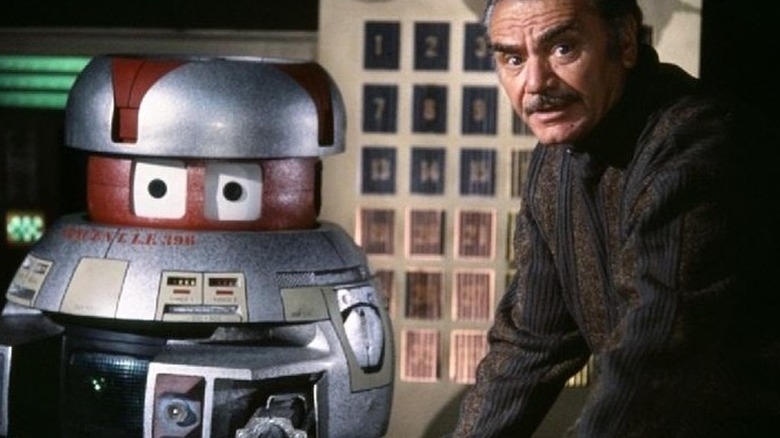

Disney's bonkers cult classic is a pause in the evolutionary chain between "Silent Running" and its silent trio of robots and the geometric buddies of "Interstellar," CASE and TARS. "The Black Hole" introduces its cute robot, VINCENT, alongside a crew of big name '70s stars; the Roddy McDowell-voiced 'bot quickly steals the movie with his smarts and empathy.

After all, VINCENT figures out what's actually happening on the secretive science vessel anchored at the edge of a black hole by simply caring about his fellow robot, BOB. BOB is barely hanging on, brutalized by sentry machines and the terrifying robotic bodyguard Maximillian. But BOB also knows what Dr. Reinhardt did to the spaceship lab's original crew. It's some grim stuff from Disney's most experimental era.

"The Black Hole" brings its namesake spacetime object to life with some beautiful matte art and practical effects, although the results can't compare to the realistic extrapolations Nolan used in "Interstellar." And the payoff is, frankly, bizarre, welding symbols of faith to humanity's durability in the face of genuine damnation. But "The Black Hole" sticks in the mind for good reason, with Maximillian's silent, murderous loyalty to Dr. Reinhardt making the movie's robots-gone-bad storyline powerful enough to ensure that classic science fiction fans remain a little wary of robot sidekicks.

Contact

It's sheer coincidence that 1997's "Contact" also has Matthew McConaughey in it, but this movie's method of blending science and faith makes it worth watching in addition to McConaughey's later sci-fi blockbuster. Carl Sagan imbued his original novel with a full-throated attempt to bridge the gap between the mathematic and the divine, and Robert Zemeckis's adaptation embraces that theme with an earnestness that borders on cheesy. But the film holds up, in no small part due to some great camera work. A deceptively simple hallway sequence uses mirrors to visually portray the characters' fear of mortality and of loss, and the film's jaunt through space is a colorful showstopper that still elicits awe.

While some of the film feels as dated as Tom Skerritt's lush mustache, solid performances carry an emotional impact that remains timeless. John Hurt as the joyously eccentric billionaire S.R. Hadden lightens the movie's heavy emotional load, and a gentle performance by veteran character actor David Morse provides a bedrock of love and acceptance that turns Jodie Foster's metaphorical first contact experience into something full of earnest hope.