'Cocaine Cowboys: The Kings Of Miami' Director Billy Corben On Revisiting The Drug Trafficking World In A Netflix Docuseries [Interview]

Fifteen years after the release of his cult-classic film, Cocaine Cowboys, director Billy Corben is returning to Miami's cocaine wars with a new docuseries. For Corben, this subject matter comes naturally: a lifelong Miamian, he grew up seeing the headlines and hearing the tales from local reporters. Where his previous work looked broadly at the rise of cocaine and the Miami drug war, this upcoming docuseries hyper-focuses on the cocaine cowboys themselves, Willy Falcon and Sal Malguta.

Cocaine Cowboys: The Kings of Miami tracks the two superstars of the drug trafficking world, who allegedly smuggled over 75 tons of cocaine into the country. Their crimes resulted in a seemingly endless cat-and-mouse chase with police, making for a series with more twists and turns than viewers could possibly see coming.

I got a chance to chat with Corben, who painted a wonderfully vivid picture of Miami, a city he dubbed "Game of Thrones in paradise with iguanas instead of dragons." He also spoke on the legacy of Sal and Willy, along with his approach to filmmaking. Corben had fascinating insights into the editing process and even offered an explanation for the Pitbull song that leads the true-crime series' soundtrack.

So I want to start by asking, where does the pull to tell these stories about the Cocaine Wars in Miami come from? Since you've been doing this for quite a while now.

I'm a Florida native and a lifelong Miamian. We often refer to our genre at our company, Rakontur, in Miami Beach, as "Florida f**kery." I think Florida f**kery might be Florida's number one export in fact, not just from us, but just in general. It's become such a genre in news and in fiction and nonfiction. I think it was really Jon Stewart on The Daily Show that began the "Florida man" craze. And so, for my producing partners and I, Alfred Spellman and David Cypkin, these are stories from our childhood, and stories that explain our childhood, and stories that answer the awkward questions we asked our parents in childhood. So a lot of our docs are for that purpose, and to document the history of our community, our hometown.

Miami has a transient population and a lack of institutional memory. So for those of us who've been here now for generations, if we don't share our stories as Miamians, who will? Because this town transforms itself every 5, 10, 15 years. It looks different. The people are different. The turnaround in a place like this is just extraordinary and the history gets lost. And so we feel an obligation to tell the stories and share the stories. And I think we're lucky that, because Miami is such an international city — it is America's Casablanca — that this didn't just become a provincial profession. These aren't local documentaries on the PBS affiliate. There is, in fact, international intrigue in Miami and international interest about said international intrigue about Miami. It's evidenced by the fact that the Kings of Miami launched on Netflix in over 190 countries and in over 30 languages. The allure of our town, of Miami, is extraordinary.

So can you give me the lowdown of who Sal and Willy are, and why they were the focus of this series?

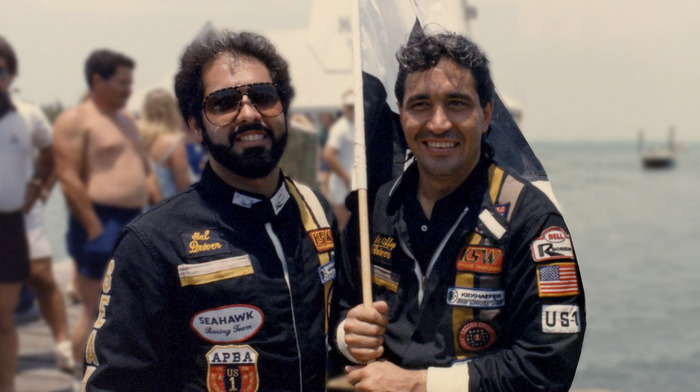

Yeah. Willy Falcon and Sal Magluta were known as Willy and Sal: Los Muchachos, The boys. Back in Miami, in the early nineties, by what we thought was the end of their careers, they were known as Willy and Sal. Newspaper headlines, graphics, and chyrons on the local news would just say, Willy and Sal. And nobody said, "Willy who?" Or, "Sal who?" Everybody knew exactly who you were talking about.

Somebody says in the documentary, something to the effect, "there may be six degrees of Kevin Bacon, but in Miami, [at] that time, there was only one or two degrees away from Willy and Sal." Everyone knew them or knew someone who knew them and their tentacles and their outreach in the community, in no small part because of their generosity, with their billions, with a B, of dollars in alleged cocaine money. They shared it with a lot of people, a lot of families.

So they bought a lot of loyalty in this town, which is a small town. Miami is also very tribal. So in the Cuban exile community, a lot of people stick together, as in any community. Miami is like Game of Thrones in paradise with iguanas instead of dragons. It's very tribal, and it's not a very communal kind of experience, unfortunately. You know, they don't call it "our-ami" they call it "my-ami." It's "my f**king ami," you know? So everybody behaves that way, unfortunately. It's a real regret of mine, that people don't really see this as the collective experience that it is, because it's not really the melting pot that we have a reputation for being.

I compare it more to... more akin to a TV dinner where sometimes the peas fall over into the mashed potatoes. We kind of self-segregate, and then everybody looks out for themselves and their own rather than the community at large. And so a lot of people had Willy and Sal's backs in those days. They were pretty insulated. They were in a city within a city, a community inside of a community that was self-sustaining and self-sufficient, and strong. [They were] politically growing in clout and economically growing in clout, both in the legitimate sectors and illegitimate sectors.

And so these guys really ran the town. They were, as the title says, the Kings of Miami. And unlike most people who were in the drug trade at that time... I would guesstimate the average career was maybe about five years, probably less. Maybe three to five years before you got killed, you got caught, or some people were able to kind of, you know, know when enough was enough... take their ill-gotten gains and start to invest in legitimate businesses. Many of those people never got caught and are still to this day running some of those legitimate empires that they built off of drug money.

There was a lot of that in Miami, but Willy and Sal operated for about 20 years. So it is an unprecedented run for domestic drug traffickers. And what's even more interesting about them is that traditionally when you get caught, that is the end of the story, right? I mean, that's the end of the documentary. Cue the epilogue title cards letting you know where everybody is today and how many dozens of years they're serving in prison, and then that's the end of the show.

But as Jim DeFede, the journalist, says in the series when Willy and Sally got caught, that was just the beginning of their story. So they get caught like... I think like six or seven or eight times over the course of the series, but like the big bust comes really at the top of episode two. And I can imagine as an objective audience member, you're probably thinking... There are another four and a half episodes of this shit. What's going to happen? They got busted. What's going to happen now? And it really is just the beginning.

Yeah! I literally have that in my notes. By episode two, half of them are arrested and I was like... where are they finding four more episodes?

If we're going to do long-form storytelling, we know we got to have enough story to sustain that. I think we all know these 4, 6, 8, 10 part documentaries, that basically take three, four hours of story and stretch it out.

Thankfully Netflix is going to be releasing some deleted scenes on their YouTube channel next week because we cut out stuff that was just as crazy and just as good, if not more so than anything that made the final cut. So there are twists and turns and holy shit moments that aren't even in the show that hopefully, everybody will get to see in the deleted scenes. So we knew there was enough story to sustain it.

We just needed to bring a little style to captivate the audience or keep you on board for long enough. And to convince you to trust us that despite the fact that these guys are in prison or in jail and about to face a federal trial, where they are looking at multiple life sentences, that there's still more story to tell.

And I hope we earned the six parts. That's my big thing. Like I watch these shows and I'm like, what am I watching? You know, like there's a screensaver kind of motion graphics, and I'm thinking, what the hell is this? Like, let's get on with the story already.

I mean, I look at this as valuable real estate. Netflix says, "Here's six hours or six parts." I take that responsibility seriously. And I respect the audience's time. If you're going to give us almost six hours of your life we better earn it, you know? And I hope that we do.

On that note, the true crime genre has really blown up in the last few years. And you were doing this back in 2006. Do you feel like your approach even has changed, with all these new shows and new styles?

On that note, the true crime genre has really blown up in the last few years. And you were doing this back in 2006. Do you feel like your approach even has changed, with all these new shows and new styles?

Oh, we work for the algorithms. That's who we work for. [Laughs] No, I mean, listen, there's a lot of interesting data and information, but I just feel that obligation creatively. I just feel like we take the storytelling seriously. We take the audience's time seriously. We take the journalism seriously, but also remain cognizant, ever cognizant of the fact that we're also creating a piece of pop entertainment, right?

And I think documentaries used to be ... I don't know that they used to be boring, but the reputation or the perception of them was that they were boring. Everybody's kind of caught on to the "truth is definitely stranger than fiction" idea here. But I think we also have an obligation to make genre pictures.

Documentary isn't a genre, it's a style of filmmaking, nonfiction filmmaking. And so you can have a documentary in any genre: romance, sports, action, gangster, musical... I mean, you name it a genre of film that you love. And there is probably a seminal film, if not one of the greatest films of all time in that genre [that is a] documentary. And so that's how we approach these things. We serve the story and we say, "Well, we're not making a documentary, we're making a gangster movie," for example. We're making a rise and fall story. A multi-generational crime family saga, and that's just how we approach it.

I'll give you an example. I have found progressively that the theme music, for example, in the genre of true crime documentaries has become kind of ponderous. You know, they kind of like droning synth and plucking acoustic guitar and sort of angsty breathy vocals. And, and I was just like... "How about PitBull?"

You know, let's be unapologetically Miami about all this and bring an aesthetic that lends itself to... you know, I talked to my composer, Carlos Alvarez early on, and I said, listen, this is a story about Miami. And this is a story about Cuban exiles losing their country, losing their homes, losing their property, losing everything that their parents and grandparents had worked for their whole lives in a brand new country, as young people with this dream in their head of the mythological American dream, right? And they were kind of guilty by geography.

You know, Miami was a time and place where a lot of young people saw their friends becoming millionaires overnight. And thinking that maybe this is the American Dream, by any means necessary. And so a lot of people, not just the Cuban exiles, but Anglos, Haitian-Americans, African-Americans, Bahamians, a lot of people got into this business because we don't have any indigenous industry in Miami. There's no companies that headquarter here. We sell the sun. We sell the Florida dream and we subsist from the hustle. We're a tech hub now. That's just the new cocaine, you know? We're a crypto hub. It's like, oh, really? The money laundering capital of the United States, we're a crypto hub now? Crypto Cowboys coming soon to Netflix, you know?

But I said to Carlos, I said, "Listen." I said, "I want every score queue in this movie, whether it's an action scene or just sort of a moody underscoring a dialogue scene, a romance scene," whatever it is, I said, "I want it rooted into in Afro Cuban music, in salsa."

And he basically invented a genre of film scoring, which is sort of like dramatic salsa film scoring. What I told him was, "if you're sitting in bed watching the show on Netflix, I want your foot to be tapping at the end of the bed while you're watching the show for six straight episodes. Give it a rhythm. Give it a flavor and make it a unique experience for the viewer."

And we did the same thing with the motion graphics and the animation and some of the song selection as well, to really gather a sense of time and place.

So how do you think tone plays into that? Because even just seeing the trailer for this, even though it's a true-crime story, it's really upbeat. They're talked about like rock stars and it comes across as kind of playful. So how were you thinking about that element of it?

It's a rise and fall. The bottom line is that all these stories end the same. Spoiler alert: dead or in prison, that's how everybody winds up in these stories. It's part of the reason why we're telling them. If there is no rise, there can be no fall.

And as a storyteller, the rise is the more spirited segment, right? I mean, you get to do the lifestyle of 20 something-year-old billionaires in Miami in the 1980s. And they lived like any of us probably would have lived as 20 something billionaires in Miami in the 1980s. The speed boats and the women and the nightclubs and the music and the wardrobe. They lived the life. And so we have to tell that side of the story, that half of the story, the rise.

I also feel like there's a real retro vibe here with the glass bricks and the wipes and the split screens. And I wanted to, again, establish setting, establish time and place, establish a tone and a rhythm. And I feel like some of the best documentaries that we've made are musicals. They're basically musicals. It's the way they're mixed, the way that they're paced, the way that they feel. And I think that you have to look at your story. This is the story about cocaine in Miami in the seventies, eighties, nineties, and zeros. There has to be a tempo to it. It has to move.

A lot of people watched the original Cocaine Cowboys, for example, and said, "I felt like I was on cocaine while I watched that documentary." And I've never done cocaine, but that was the effect. An average feature has on average, like 1500 cuts in it. The first Cocaine Cowboys had about 5,000 and it all moves in a way that it almost demands repeated viewings, cause you're still reacting to a bite and you're like three, four, or five bites later. The first time I ever saw someone on cocaine and had a conversation with them, like face to face, I didn't know what the hell was wrong with them! I was like, "What the hell is wrong with you?" And they're like, "Oh, you don't know? She was powdering her nose in the John." And I was like, "Oh wow."

It was like she started one sentence and finished another. [That's] was the best way I [can] describe it. So that was kind of the vibe. The thing is constantly in motion and these guys were constantly in motion. They're world champion offshore powerboat racers, whether they were running from the cops and in this sort of revolving door in and out of jail because Miami or, even when they were caught, it was this constant forward momentum.

And so even in what would feel like ordinarily static scenes, there's a momentum and a kinetic kind of energy to the storytelling here that I think is appropriate. I wouldn't do that for any story, you know, but I think it was appropriate for this story. And what was, I thought, brilliant about the trailer that Netflix did was that it accurately represents the tone of the piece. You know, it didn't go in sort of another direction with it. To your point, [they] didn't create this sort of moody pensive creepy sort of true crime vibe. They said, "Well, this is what Kings of Miami is. Let's sell it the way that it is." And I really appreciated that.

I'd love to also hear about how you approach building connections with the interview subjects. I know you've said that you don't use fixers or producers and hunt people down. So how do you get them in front of the camera? How do you make those connections?

I'd love to also hear about how you approach building connections with the interview subjects. I know you've said that you don't use fixers or producers and hunt people down. So how do you get them in front of the camera? How do you make those connections?

Yeah. And as we take on more projects, we certainly have help, but on this show, we did not. We worked on it for 12 years and we made it by hand. We're a boutique operation in Miami Beach. It was a labor of love, really, for a long time.

I don't go to a lot of nightclubs. I never really did. I like dive bars. And so if you go to some old dive bar in South Florida, and you just pull up a stool next to like the crustiest old person you can find sitting at the bar — like just someone who's kind of like a barnacle, just like stuck there at the bar — and just share some whiskey and start talking, you will invariably wind up next to a former drug smuggler, a deposed dictator, someone fresh out of federal prison on a Medicare fraud rap or whatever.

It's just Miami. It's just a sunny place for shady people. And so that's like my pastime. And so you just kind of make those connections with people. And then when we made the first Cocaine Cowboys... you kind of get a reputation. And my producing partner Alfred Spellman likes to joke — and there's always truth in sarcasm —that when people get released from prison in Florida, their first call is to their mother, and their second call is to us to make a documentary about them.

That didn't happen 15, 20 years ago, but I feel like we're in kind of a postmodern era, particularly with just the ubiquity of nonfiction content, this kind of golden age of documentary filmmaking. People are more self-aware. You have criminals now documenting their crimes for the future documentary series... and also very helpful incidentally for the authorities to bust them and have evidence against them.

Obviously telling this as a docuseries versus a documentary gave you a lot more space and time. Were there other things that you were thinking about, even just creatively, putting this together as a series instead of a single big piece?

Well, I'll tell you, cutting the episodes down was tough. A lot of difficult decisions, and thankfully, YouTube is very bullish about their YouTube channel and sharing ancillary content and bonus features.

You want to maximize, again, the audience's attention and streamline the storytelling in the most efficient way. And of course, you need buttons at the end of each episode, cliffhangers, to keep the audience binging it and coming into the next episode... Leave them wanting more.

But listen, some of these episodes have cliffhangers in the middle of the episodes or during the episode, so it wasn't hard. You have to start thinking that way. The way I actually thought of it... Yes, it's six different parts, but I see it as a trilogy of feature docs. So if you have to break it up, I recommend watching one and two, then three and four, and then five and six. I think, structurally that's sort of like the beginning, the middle, and the end of this story.

Working that way was helpful because we have a timeline, sort of a line of cocaine that serves as a timeline that can move backward and forwards because a lot of these events from episode to episode happened concurrently. So you need to understand when we're flashing back, where we are, and there's so many characters and so many events that occur over the course of the 20 plus years in this story.

We use that device, but also, each episode is chronological, but it has an internal chronology in each episode. And it has an internal kind of three-act structure in each episode, and then every two episodes, and then in all six episodes. So sometimes it took a while to be like, "Well, what do we cover in which episode?" And we sort of move some pods around, which was actually kind of fun. I enjoyed that experimentation. It's the democratization of that process with nonlinear editing. You know, when I started... When I went to film class, I was shooting on film and editing with razor blades and scotch tape for crying out loud.

So this is like, so fun to be able to say like, "Well ..." And we'll get a note or we'll get an idea and I'll be like, "Well, we don't know until we try it, right? So let's go for it. Let's ... It's just a copy and paste, right? So let's see how it works."

So there was a lot of experimentation through this process, but once we nailed down, again, the structure that we wanted in each episode, the structure we wanted every two episodes, the structure we wanted over the course of the arc, and the threads for the entire series, then it was a lot of fun.

I feel like we were locked in. With all those split screens and the wipes... There's a lot of integration. There's a lot of customization. There's a lot of things that need to be locked and loaded in order for those things to be finalized. And it was a challenge, but it was a fun one.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

***

All six episodes of Cocaine Cowboys: Kings of Miami are now streaming on Netflix.