Watch: /Film Visits Mexican Locations That Inspired 'Coco' With Co-Director Adrian Molina

Disney/Pixar's Coco is bursting with authenticity. From the set designs to the family dynamics to the music, the whole film feels like a love letter to Mexico. It has a story that works for everyone, but goes out of its way to give a special nod to a culture that isn't often represented on the big screen. That attention to detail paid off in a huge way: Coco became the highest grossing movie in Mexico's history and has made more than $730 million worldwide.

So how did the film that survived a justified uproar when Disney tried to copyright the phrase "Dia de los Muertos" (Day of the Dead) become one of the most culturally accurate and pure-hearted films in recent memory? Immersion, research, and respect.

In honor of Coco's home video release, Disney flew me and a handful of other journalists to Oaxaca, Mexico, where we followed in the footsteps of the filmmakers' research trips and visited many of the neighborhoods and locations that inspired the creation of the movie. Learn more about the making of Coco below.

Monte Alban

One of the oldest cities in Mesoamerica, Monte Alban was a major city for the Zapotec people from 500 BC to around 800 AD, serving 25,000-35,000 people at the height of its power. There are still dozens of structures left intact, and we had the opportunity to walk around and explore the area on foot. The sheer size of these ruins, situated on top of a mountain overlooking Oaxaca City, was staggering. For Lee Unkrich and Adrian Molina, the director and co-director of Coco, the ruins of Monte Alban provided inspiration for the movie's Land of the Dead. If you look closely at the base of the colorful and elaborate buildings in the movie, you can see some foundations that resemble the structures in Monte Alban. But the ancient site's most prominent influence in the film comes when Miguel and Hector visit a nearly-forgotten section of the spiritual realm to retrieve a guitar; it's clear that Monte Alban heavily shaped the production design of that area.

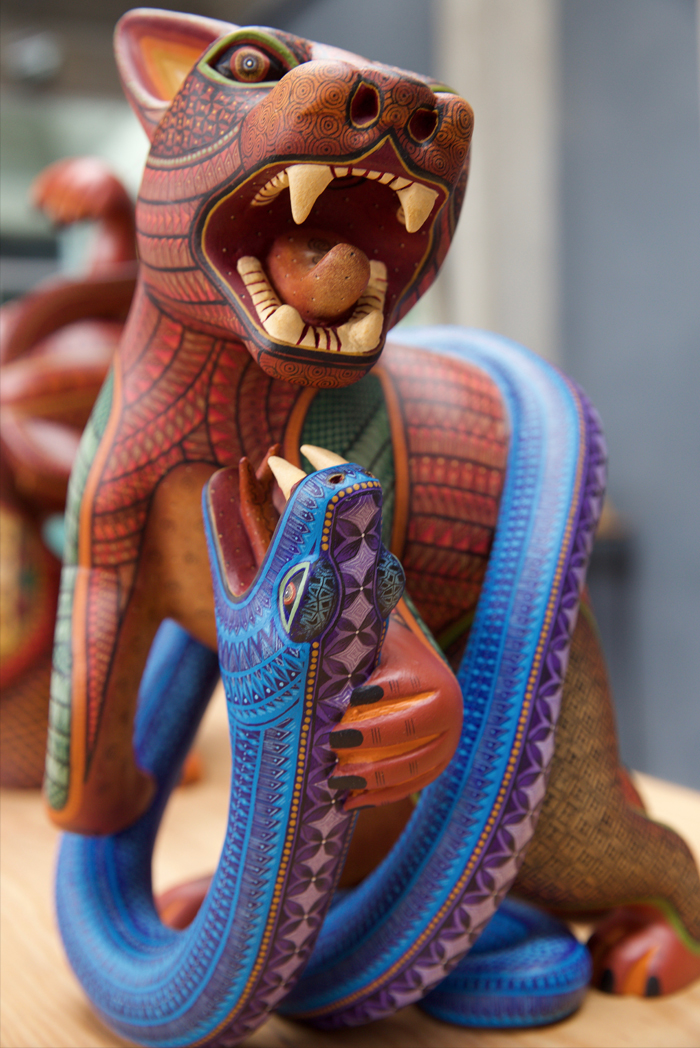

Alibrijes

About a 30 minute ride from Oaxaca City lies the small Zapotec village of San Martin Tilcajete. The town is known for its alibrijes – carvings of spirit animals from 20th century Mexican folklore. Some families specialize in creating felines, some make hawks, but one particular family's achievements outshine the rest. Jacobo and Maria Angeles, a husband and wife team of internationally renowned sculptors and artists, specialize in making all types of alibrijes. Their work is featured all across the world, including in the Smithsonian museum. We had a chance to meet them and visit their workshop, where we saw some of the incredibly detailed pieces they've produced. It's truly some of the most beautiful and jaw-dropping artwork I've ever seen.

Jacobo and Maria have taken their success and channeled it back into their local community: they've built a school that accompanies their workshop where kids from San Martin Tilcajete and the surrounding villages can come and learn their craft. In addition to being a phenomenal hands-on learning facility, this school may very well have saved the lives of some of these students. Our guide told us how some of them might have turned to selling drugs, but instead they're now on a path toward careers as artisans.

Papel Picado

In another village, San Jeronimo Tlacochahuaya, we were invited to the home of Marco Antonio Sanchez Martinez, an artisan who makes papel picado. Martinez creates these elaborately designed banners by hand, literally hammering out shapes with a hammer and chisel from stacks of stylized paper that are often 40 or 50 sheets thick. It's a time-intensive process, but the results are lovely; his pieces have sold to customers all over the world, and we saw papel picado hanging everywhere during our trip. The artists at Pixar took a liking to it, and in addition to the movie's opening sequence (which tells the story of Miguel's family through papel picado), you can see it in the background of Coco's version of Santa Cecilia.

Unfortunately, the art form no longer receives financial support from the Mexican government, so it's in danger of dying. (There are only about two other people in all of Oaxaca that still create papel picado by hand.) Martinez is teaching others the technique in the hopes that it doesn't completely disappear, but without government funding, it's unclear how long anyone in Mexico will be able to continue to make a living solely through the creation of these paper pieces.

Family Dynamics

In addition to aiming for a measure of visual authenticity, the filmmakers also wanted to make sure they nailed the interpersonal dynamic of family members who both live and work together.

Shoemaker Marco Antonio Vera Santiago, who learned the trade from his father, normally makes about seven pairs of shoes per day in his store in Oaxaca City. These custom shoes are made completely from scratch and all by hand. For comparison, it normally takes about 60 people to make a shoe in a factory: designers, people who work with leather, those who specialize in insoles, sewing, and more. Santiago does it all himself, including the designing; customers will come in with a loose idea for a shoe, and he creates it to their exact specifications. From the initial design to the final product, he can complete a pair of shoes in about three hours.

In the nearby village of Teotitlan del Valle, master weaver Nelson Perez runs a family-operated business and creates blankets, rugs, purses, coats, and more. In the 1980s, an entire generation of artisans switched to consumer dyes because they were easier to produce. But Perez and his family still use all natural dyes, extracting yellow from marigold leaves, green from chamomile, and indigo from mixing the crushed leaves of an anil plant with water and leaving it for 20 days before harvesting the results.

I spoke with Coco co-director Adrian Molina about how visiting locations like this translated into what we saw in the film:

"A lot of this is very useful in terms of seeing the dynamic of a family business and a tradition that's passed down from one generation to the next, to the next. So we got to see weavers, potter makers, shoe makers, mezcal makers – all of these different businesses where it really is a family business. The lifestyle is living with the people, working with the people, and having your part to play in the family. And you never know what's going to be inspiring when you go to visit a place, but for us, seeing so many family businesses was really useful. Getting a feeling for the dynamic of that household that was also a place of work where your co-workers are also your family, and the kind of pressure but also unity that goes into that situation."

(To hear much more from Molina, be sure to watch my interview with him from Monte Alban.)

For years I've heard about research trips that the Pixar and Walt Disney Animation teams would go on before diving into production on their movies, and I'll be honest: I've occasionally wondered if trips like that were necessary considering how much information you can find online. But having followed in their footsteps through Mexico, it's clear that physically visiting an area allows these teams to immerse themselves in a way that wouldn't result in the same specificity otherwise. Getting all of the little details right – the lived-in feel of a workshop, the mannerisms and colloquialisms of the people – can often be the difference between a failed but well-intentioned attempt to capture a culture and something authentic that connects with audiences around the world.

Coco is available on Digital HD, Blu-ray, and DVD right now.