How Did This Get Made: A Conversation With 'Streets Of Fire' Co-Writer Larry Gross

In 1982, an action comedy called 48 Hrs. took the world by storm. Not only did it finish seventh at the box office that year, but it also launched the film career of Eddie Murphy and spawned a slew of buddy cop imitations. Although a true sequel to 48 Hrs. wouldn't come until 1990, a follow-up of sorts came out two years later: Streets of Fire.

To understand how Streets of Fire came to be (and its relationship to 48 Hrs.), I sat down with cowriter Larry Gross to discuss the film's origins—and his as well.

Streets Of Fire Oral History

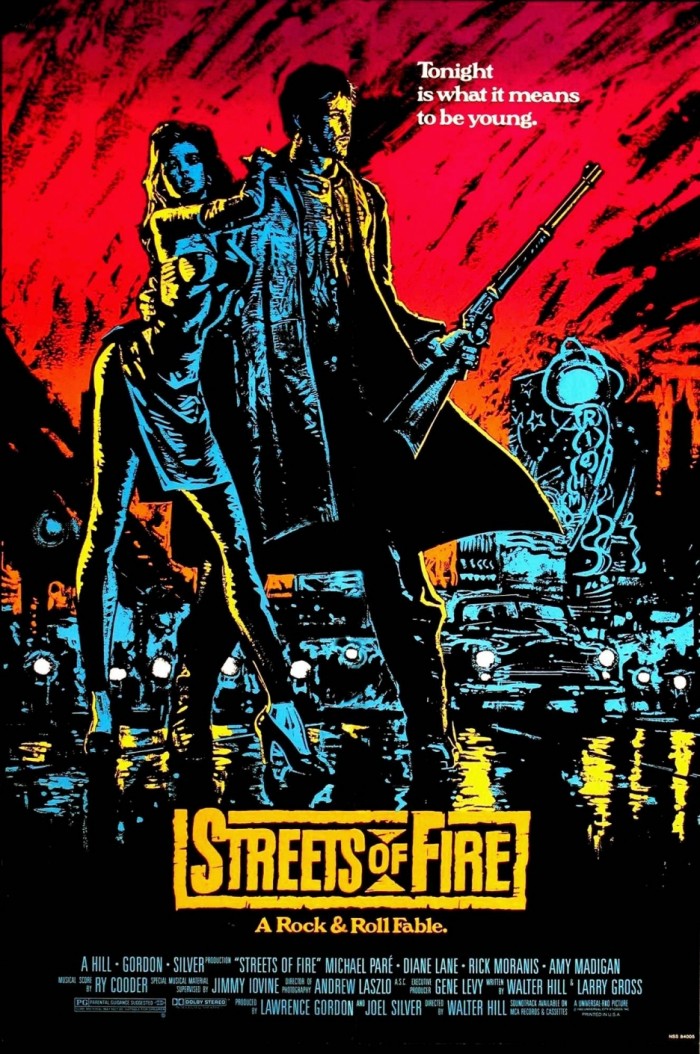

How Did This Get Made is a companion to the podcast How Did This Get Made with Paul Scheer, Jason Mantzoukas and June Diane Raphael which focuses on movies. This regular feature is written by Blake J. Harris, who you might know as the writer of the book Console Wars, soon to be a motion picture produced by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg. You can listen to the Streets Of Fire edition of the HDTGM podcast here. Synopsis: Set against a brooding rock & roll landscape, a mercenary tries to rescue his ex-girlfriend after she is kidnapped by a vicious gang.Tagline: A Rock & Roll Fable

Part 1: The Bartender and The Driver

Larry Gross: It all started for me when I was 12 years old. I went to visit my dad in New York City; he worked in Midtown, and when I got there he didn't know what to do with me. So he sent me to the Museum of Modern Art. And when I got there, they were screening North by Northwest. I have a visceral, neurological memory of the excitement of that film. The suspense of that film and the fun of that film. After that, I started going into the city by myself on a regular basis, and it happened to correspond to an explosion in Manhattan with revival theaters.Blake Harris: Would you go alone, or did you have friends with similar interests?Larry Gross: Occasionally I would drag my parents with me, but generally these were very solitary experiences for me. People have different sociological habits or dreams, and my sociological dream, as it were, was to be around older people. I played basketball with older people when I was a kid. I was kind of a mild prodigy at basketball, but as I got older, I submitted to "White Men Can't Jump" syndrome and I failed to develop. After that happened, movies fully took over for me.Blake Harris: As a viewer, or were you thinking about making films yourself?Larry Gross: Well, the first idea in my mind was that I wanted to pass myself off as an authority on movies. And early on, I learned about the cinephiles who had become filmmakers. So the idea was planted early on that I would become one of those guys. I had this thing mapped out where I'd become a great filmmaker like those critics had been. I would take my knowledge of film history and become a great filmmaker, like they did.With this path in mind, Gross saw as many films as possible during his teenage years and then, in college, started writing screenplays with a friend. Larry Gross: During my first two years after college, I didn't really know how to make the transition. L.A. was always kind of a distant plan. And then what happened in my case was sort of three things happened at once: 1) I had an unhappy love affair; 2) I had a very painful breakup with my writing partner; 3) my brother got a development job out west, in television, for ABC. And he helped me get a job out there.The job entailed working for a British television director named David Greene, who was coming off of two historically high-rated miniseries: Roots and Rich Man, Poor Man. While working or Greene, Gross also continued writing screenplays on spec. Larry Gross: The script that kept getting me meetings was called The Bartender, and it really was like a flat-out imitation of Walter Hill's The Driver, in a way. That script got as far as to have a director attached: Ted Kotcheff. And through that, for various reasons having to do with the writers strike in 1982, Kotcheff asked me to rewrite a script for him that was in production: Split Image. That was very big for me. It was a real movie with a real cast and it was shooting. And they needed several scenes revised. So I went on location and worked with them. And even though the movie had almost no release, it then led to Ted hiring me to do a similar production rewrite for a good deal more money on the next film he did. Which was First Blood (the first Rambo movie).Blake Harris: Ha. Nice!Larry Gross: The point is that those two rewrites on real movies, the fact of them, got my name around. And around that time, by a series of social accidents, I went to dinner with Walter Hill. And we became friends. During that time, we discussed movies, we discussed politics and we discussed women; but we never discussed work. I certainly made it unmistakably clear to him that I knew his films well and indicated that I was a fan, but I never raised the question of working for him.Blake Harris: And what was going on in Walter's career at the time?Larry Gross: It was a unique period of frustration, relatively speaking. He'd had some success, but then he had a series of setbacks. And there was also the scandal around The Warriors; any success had been eclipsed by the killings in the theaters. So there was that, as well as the noncommercial success of Southern Comfort and Long Riders and the fact that there was a writer's strike. All of that meant that Walter hadn't worked in a while. Meaning a year or so. And what happened was the strike ended and the studios didn't have a lot of ready scripts. So this clever colleague, Larry Gordon, dusted off a script that had been shuttling around development and got it greenlit at Paramount with his friend Michael Eisner. And that script was 48 Hrs.

Part 2: 48

Larry Gross: 48 Hrs. had been in development for most of the '70s. It had been rewritten 9 or 10 different times, never to anyone's complete satisfaction. And Larry Gordon's idea was to revise it along the lines of being a black/white story. This was at the time of the ascent of Richard Pryor. And basically everyone in town was dreaming of developing the next Richard Pryor movie. He was hot and he was cool and he was new. I mean, the ferocity of people's enthusiasm for Richard Pryor at that time was really kind of amazing. He crossed that barrier into being artistic and commercial at the same time.Blake Harris: So the plan was to rewrite 48 Hrs. with Pryor in mind?Larry Gross: Exactly. And Walter was about to do a draft when they found out Pryor wouldn't be available. So he was sort of a little bit stalled. And then his girlfriend, who was an agent, said: "I've got this client who you should maybe consider." He was a young guy, never done a movie before, on "Saturday Night Live."Blake Harris: Ah, so that's how Eddie Murphy got involved.Larry Gross: With Eddie attached, Walter had done the beginnings of a new draft with Larry Gordon's second in command, a guy named Joel Silver. And they were looking to bring in a new writer. And here's a funny coincidence. Walter was looking around and thinking about suggesting me to Joel, but then Joel proposed my name.Blake Harris: How did that happen?Larry Gross: Well, the reason Joel proposed me is that Joel had just come off of a couple of months where he had been at Polygram Pictures and they had made the little movie I rewrote for Ted Kotcheff. And he knew that I had rescued it on the set. So when Walter was about to bring my name up, Joel brought my name up. So when I was brought on, this movie was moving forward at a feverish pace. It had a greenlight and was going to go into production despite not having a script that everybody liked.Blake Harris: And why was that? Without Pryor, why the feverish greenlight?Larry Gross: There were a couple of reasons. One was that the budget of the movie was relatively miniscule and, bottom line, Michael Eisner trusted Larry Gordon. They'd had a somewhat similar set of circumstances on the making of The Warriors. They had begun with an unfinished script and Walter had improvised a great deal of it during the making of the film. So Eisner trusted that, at a price, they could pull this off.Blake Harris: Gotcha. And what was the other thing?Larry Gross: Under Eisner, as the head of production, was a guy who was at that particular moment was kind of melting down: a guy who had a notorious drug problem and wasn't getting along with Eisner. And that man's name was Don Simpson. And because of what was going on with Simpson, they pretty much ignored us and our project. So, for the most part, we were left completely unattended to make the movie we wanted to make. A movie which we only vaguely knew what it was. I said we only vaguely knew what it was in the sense that the plot and the situation and circumstances never altered, but what we didn't know was who Eddie Murphy was and what his interaction on screen with Nick Nolte would be like and could be like.Blake Harris: And what was Eddie like? This unknown quantity.Larry Gross: During the first two weeks of production, which was the brief location shooting that we did in San Francisco, Eddie was nervous, unprepared and basically terrible. Not funny. In fact, at the end of those two weeks, Paramount wanted to shut the film down and recast.Blake Harris: Oh, wow.Larry Gross: But Walter felt extremely embattled and hassled by studio anxieties. He felt that it was an absolutely do-or-die thing that he be able to stand his ground and not replace Eddie. So that was part of why a change did not take place. But also, something else happened. Up there in San Francisco with him, working on the script, we began to feel at the end of the eleventh or twelfth day of production that we'd begun to see glimmers of something better.Blake Harris: And what do you attribute that to?Larry Gross: We just understood certain things that we hadn't understood at first. We saw certain things Eddie didn't seem able to do (at the time), and we'd seen other things he did seem able to do. And all that conjoined with Walter saying to the studio, "Let's get him an acting coach and make sure that he goes home every night (and doesn't party) so that he's awake and ready, and I promise you he's going to work on the film. And if you replace him, you're going to have to replace me." So the studio threw up their hands and said: Do what you want. And Eddie got better every day. We knew by the next week he was going to be okay. And day after day after day, he just got better and better.Blake Harris: What did Nick Nolte think about Eddie? Did that frustrate him at all?Larry Gross: He was a professional. He liked Eddie, and Eddie, to his great credit, was immediately in awe of Nick. I will never forget him saying, "Nolte makes you act." And that's a very profound statement for a 20-year-old kid at the time. It's what the other guy in the scene is doing that determines what he can and will be able to do.Blake Harris: Since, as you mentioned, the script was still in flux, how did all of this change—if at all—how you rewrote the script?Larry Gross: What we understood was there was a vein of back and forth between them that we could focus on in the writing. Early on, I made this analogy to Walter with regards to how we should write the scenes: Think of it as a jump ball situation in a basketball game between these two guys. They walk into the scene and compete for the ball. We should write the scenes as if it were a sporting event. And here was another thing: Eddie, coming from the live medium, needed to experience the present moment. What I noticed was I'd written various scenes where Reggie Hammond talked about things that were happening off screen or had happened off screen in the past, and Eddie didn't do well with those lines. He read them fine, but they just didn't work. But when he was reacting to the situation, or responding to Nick's hostility, he lit up. So we said: Let's rewrite everything to be in the moment. And let's also find out what he wants to say. So he improvised a tremendous amount of it as well.Blake Harris: What did Paramount think of all this?Larry Gross: Well I remember, maybe two weeks before production ended, we showed Paramount a rough cut of assembled footage. They came back and said, "We love it; [jokingly] how can we edit Nick Nolte out of the movie and make it just an Eddie Murphy film?" That was perhaps the single pleasantest moment in the process with Paramount, and it's actually what led to Streets of Fire getting started.

Part 3: Not Another 48 Hrs.

Larry Gross: Streets of Fire began in the euphoria of knowing that Paramount really liked 48 and wanted to be in business with us if they could. What happened was that after we screened that cut for Paramount, Larry looked at Walter and said, "Paramount is pregnant; let's get something and set it up right away." Walter knew what he meant—that we were in a great position here—so he said, "We can do this two ways: present an idea now and get a deal done, or write a script on spec and get a lot more money." Walter proudly considers himself a capitalist, so he suggested we do the latter.Blake Harris: And how did the latter wind up being Streets of Fire and not, say, something more similar to 48 Hrs.?Larry Gross: Well, Walter and I talked about it and he said, "I've always wanted to do a movie about the hero of a comic book. But I don't like any of the comic books I read, so I want it to be an original character." He wanted to create his own "comic book movie," without the source material actually being a comic book. And, from there, we started talking about Tom Cody.Blake Harris: So just to clarify: You decided not to try and arrange a deal ahead of time with Paramount, but instead write a spec script and sell it to the highest bidder?Larry Gross: Correct. It was written as a spec, but Paramount was the first studio that we brought it to. And this is where agents and legends and stories happen. Jeff Berg (Walter's agent), Larry Gordon and Michael Eisner got into some kind of a fight when the script was finished. We learned later that, I believe, Eisner rejected it on the grounds that it was too similar to Indiana Jones. Conceptually. So they didn't pull the trigger and Berg ended up selling it to Universal.Blake Harris: Given the success of 48 Hrs., did you guys ever think about trying to attach Eddie?Larry Gross: No. There was always the idea that we were going to discover a new Steve McQueen, you know? A young, white guy who would ride a motorcycle and have a carbine over his shoulder and be a mainstream icon. And we saw them all. I mean we saw everyone. Eric Roberts. Tom Cruise. Patrick Swayze. Everyone, everyone, everyone, everyone. And we wanted Tom Cruise. But he got another job the day before we made him an offer. Our dream cast, who we met and we wanted, were Tom Cruise and Darryl Hannah. And we couldn't pull the trigger on either deal in the right moment of time and we lost them.Blake Harris: What did you like about Tom Cruise?Larry Gross: He just walked into the room and you knew. Everybody knew. It's very rare that it happens like that. To walk into the room with such...Walter has likened it to this quality that Prince Hal has in Henry V: He knows he's the guy, he doesn't need to be told. He believes in himself in a different way than other people. It's more than confidence, and it's certainly not arrogance. It's just the opposite. And Tom Cruise was that way.Blake Harris: Gotcha.Larry Gross: The other person who was sort of that way—though he wasn't right for Cody—and may have been the best thing about the film, was Willem Dafoe. David Giler, who produced movies with Walter, was dating this young film student—this tall, intellectual brunette—who made an artsy underground film. Her name was Kathryn Bigelow. And she said to Giler, "There's this guy in my movie that might be

right for your movie."

Blake Harris: Ha! And how did your relationship with Walter evolve as you started working together?Larry Gross: There are infinite numbers of possible working relationships between a writer and a director. The likely best one is the one where the director writes, either some or a lot. Usually it's best to work with a director who writes, because the director who writes respects but does not idealize the writer; he does not believe (the writer) has magic coming out of his fingernails. Nonwriting directors go through a period of idolizing and loving the writer and then go through an invariable period of disenchantment when they discover, as they invariably do, that the writer does not have gold coming out of his fingernails.Blake Harris: Which obviously wasn't the case with Walter...Larry Gross: Right. So the way we mainly worked was Walter would work out ideas in fairly great detail. I would do drafts and then he would go through them. He did not love creating scripts from scratch; he loved rewriting. Everything that he rewrote came through him and his way of doing things. Somewhere in the process of working with him on Streets of Fire, I began to have a pretty good sense of what I might put into a scene that he would dis-include and what I think of that would have a better chance of being something he didn't need to revise. In other words: I began to develop a strong sense for knowing how to sound like he did.Blake Harris: And as you guys developed a creative rhythm, can you tell me a bit about the evolution of the film? Logistically, I meanLarry Gross: Well, the big creative thing...there were two issues. One was the casting of Tom Cody. As I mentioned, we couldn't get certain people we wanted. Then we saw a movie called Eddie and the Cruisers and we really liked Michael [Paré] in it, and we decided to go with him. We were very excited about Diane Lane because she was starring in two excitedly hyped Francis Ford Coppola pictures that were being done in Oklahoma. So we had the approval of sort of picking the person that Francis Ford Coppola picked. And we were affected, as everyone was at the time, by the success of a movie that no one had expected very much from. The movie that brought Don Simpson back with a vengeance, which was that dance film with Jennifer Beals...Blake Harris: Flashdance?Larry Gross: Yeah. We were fascinated by the success of Flashdance and we decided, in the midst of writing, that our movie was going to be a musical. Like Flashdance.Blake Harris: How? Why? That's such a big leap.Larry Gross: We just decided. We just decided. We said this movie is a stylized movie, it's not so different from the world of a musical. And there were a few other things that contributed to that direction. One was the decision on Universal's part, a crazy decision, to shoot the movie almost entirely in the studio under a tarpaulin. They built this gigantic tarpaulin, and the Battery and all these other places were built as real places. The Richlands. And just so you know, this is the early '80s and you had stylized films—like New York, New York—that were all done on set and that idea was in the air. That idea of a totally artificial universe. The point is that we had in mind one sentence inspired by George Lucas: "in a galaxy long ago," a futuristic past. That was in our heads...there's the past and there's the future, sort of. So the big creative world decisions were music and then the other thing was, the other guru, "divinity," behind Streets of Fire was John Hughes.Blake Harris: Really?Larry Gross: We were in the universe of the teenage movie. Teenage reality. So we said here's what's going to be weird about the world of our movie: No one's going to be over 30. The world is a high school, essentially. And Tom Cody will be the football hero. And Willem Dafoe is the greaser. Remember: You had John Hughes at the time, and then you had Coppola making two high school movies: The Outsiders and Rumble Fish. So Walter said we're going to make a high school movie that's also going to be a comic book and also going to be a musical.Blake Harris: That's a lot of "also's." Did any of those genres/styles contradict?Larry Gross: Well, Walter felt strongly about certain story decisions. For instance: No one is going to die in this movie. When Tom Cody's rifle blows up a motorcycle, we're not going to see any blood, and we're not going to see anybody die. He'd say it would be inappropriate to direct this movie if there were any blood. We're in the world of Cocteau, we're in the world of Beauty and the Beast. This is a fairy tale. Now...he neglected to mention that some fairy tales are very violent. And I'll say one thing to tie this together. As with 48, we would meet with the editors on the weekends and look at footage. And I have to say, it was a 14-week shoot and after about five weeks, I remember one night I turned to Walter and said, "This movie is somewhat weirder than we thought."

Part 4: The Phantom Hope or Dream

Larry Gross: Why was it weirder than we thought? We just didn't anticipate what the combination of elements was going to be. We had a very conscious design concept of the movie, but I think we didn't fully grasp how strong it would be, in terms of the combination of elements. In a way, I think Streets of Fire was about expanding The Warriors concept to a bigger stage. But when expanding it to a bigger scale, it changed. The movie's bigness of size—compositionally—changed the meaning of things and made it more of a fairy tale.Blake Harris: I can see that, the relationship to The Warriors.Larry Gross: The Warriors, it was bewoven with a unique sense of realism. The fact that they made a deal with real gangs to be extras in the film. There was a true Godardian dialectic going on between artifice and reality. It's a very real-world film, in some respects, but it's very artificial at the same time.Blake Harris: It is, you're right.Larry Gross: But the point I'm trying to make is that we did that again, but we put the emphasis on the artifice. And we didn't fully...I want to say we had too much integrity. We went further with that, perhaps, than we should have. I don't know. I can't put everything together about what didn't work, but the most damaging thing is that we didn't have the right actor for Tom Cody. Maybe if we'd had Tom Cruise, we might have had a success. But our commitment to be stylized was thorough and conscious and maybe too extreme for the mainstream audience.Blake Harris: I would say that the bigger issue would be the musical aspect. That's something absent from Se7en and RoboCop and other stylized films with varying degrees of gore.Larry Gross: That very well may be true. Hmmm....Blake Harris: Personally, if someone tells me that something is a musical it immediately changes the way that I will perceive it. That doesn't mean it's good or bad, but it just alters my perception of the content.Larry Gross: Well it's funny because I think the musical sequences are actually some of the best stuff in the film. It's paradoxical. I think you're right, though: that the musical aspect might have confused the audience.Blake Harris: Yeah, again I'm not saying that independently those scenes or that component to the film is good or bad, just that it changes the way I access a movie.Larry Gross: It may have confused the audience. The biggest favorable review the piece got—and which I still have somewhere—is from the wonderful rock 'n' roll critic Greil Marcus. He wrote an essay about how Streets of Fire was the first and only film that had figured out how to take the aesthetic of rock videos in a serious direction. And that it represented a different level of approaching that format than anyone had ever done before. And we talked about rock videos all the time. Our goal was basically to distend rock videos into something else.Blake Harris: I never thought of it that way, but that's interesting. The timing of the movie, coinciding with the rapid growth of MTV. That's really interesting...Larry Gross: You know, there are a lot of ways you can determine whether a film is good or bad. But one way is the impact it has on other filmmakers. You know the joke about the Velvet Underground that Brian Eno made? "The Velvet Underground's first album only sold a few thousand copies, but everyone who bought one formed a band." The point is that whatever is good, bad or indifferent about Streets of Fire, it had a huge impact on other filmmakers. The two movies that came out in the years after that are completely saturated in the iconography of Streets of Fire are RoboCop and Se7en. Se7en's taking place in another world. It's not New York. It's not Chicago. A world where it's raining all the time. Always dark. Always night, just about. Those are two very successful movies that figured out how to do the stylization with the appropriate amount of gore that they hooked the audience. And I think that if we'd done more gore, our chances of hooking the audience would be greater.Blake Harris: You said one way to measure success is how it affects others. So I'm curious: Are you happy with how the film turned out?Larry Gross: We all knew in our hearts that Michael was disappointing. We felt that we had compensated adequately in making a fun, exciting, stylized world. You know, I was disappointed in one aspect: a voiceover from Tom's sister that we had, which Walter later decided to cut. Um, there were a couple of things in the narrative that I felt went out that probably should have stayed in. At the same time, I was myself knocked out by what Walter and (cinematographer) Andy Laszlo and our editor were doing visually on the film. And I felt, as I watched the post-production process going on, I just saw the film getting better and better. More impressive. To the point where I thought it was going to do well. And I thought that we had done what we set out to do. Created the world that we set out to create. I was shattered when the film didn't perform. That broke my heart. I was going to be somebody who had written two successful movies in a row and, if that happened, I would have likely been on track to direct movies. That isn't what happened though. I hoped, by the time the movie finished, that it would be whipped into a shape and design that would have a real impact. And then it didn't, and that was sad. It was a movie that was built to succeed. It's funny. The movie screened very, very well. I remember, after the first screenings, people told me that I was going to be rich for life. There was tremendous love and confidence.Blake Harris: Was there a moment when you realized that it wasn't going to succeed? Or was it more of a gradual process?Larry Gross: Well, Walter and Joel, as was their wont, set up another movie. This one I was not involved in: a comedy called Brewster's Millions with Richard Pryor. And they were shooting, and I came down to set. And Joel got off the phone with Universal and said, "We're dead." We sat down, I remember, in a little park. In downtown LA. And we started giggling, in that way people do when things are terrible.Blake Harris: Laughing instead of crying?Larry Gross: Exactly. And there's the song in the movie called "Tonight Is What It Means to Be Young." And I remember, in the park, Joel saying, "Today Is What It Means to be Dead."Blake Harris: So what did it feel like? To be dead? Those guys already had another movie—and longer track records—so you were probably more "dead" than the rest of them, no?Larry Gross: You know, I didn't understand something at the time. I was in better shape than I thought. Meaning...this gets into a whole complicated story about how failures and successes affect writers. Neither failure nor success damages writers the way it damages or helps actors and directors. Someone put it to me once: A writer's job is to write a script that gets made. Once he's done that, he's viewed as having done something good. Regardless of how the film turns out. "You did your job" is how Walter said you're viewed when a film you've written gets made. You're on the plus side of the ledger. Albeit if [the movie does] very well, obviously, it can have additional good. So I worked very, very heavily for the years after that. A lot of producers came to me with a lot of ideas for movies. And I was able to set up a lot of my own ideas. I was in good shape.Blake Harris: Well, as a writer myself, that's kind of nice to hear.Larry Gross: Yeah. Success for a writer is about the possibility—the phantom hope or dream—of controlling the material. And that's what every writer hopes to achieve to one degree or another. Now, was I able to ultimately achieve that? That's another conversation for another day.Blake Harris: Well, to finish up this conversation, I have one final question: Did you ever work with Walter again?Larry Gross: Oh, absolutely. We're working together now. I mean, we're always talking about ideas. But let me tell you something: As much as I respect and admire Walter as a filmmaker, I happen to like him more as a human being. He's just a really good guy. A legendarily good guy. Here's the thing about Walter that's not like other people in Hollywood: If you want somebody's opinion about X and you ask 20 different people, you get 20 different opinions. But when you talk about Walter Hill to 20 different people, you get the same opinion. They all like Walter and they all describe him the same way.Blake Harris: Which is...?Larry Gross: Michael Mann put it to me very simply once: Walter Hill, a straight shooter. Those are the words. That's the best summary of the take on Walter. It's what everyone says. It's what everyone thinks and feels. Some people care more about his films, some people care less about his films. But everyone knows he's a straight shooter. Everyone knows that the people that work around him like working around him. Everyone knows that they get dealt with in a straighter, less hysterical, less bullshit way. Whatever. The point is: They know that whatever else they're going to get when they work with him, they're going to get a decent human experience. Because Walter Hill is a straight shooter. He lies, dissembles and manipulates the absolute minimum required.Blake Harris: Ha!Larry Gross: And by the way, this is not enough of a recorded fact about Hollywood, but that actually counts in your career.