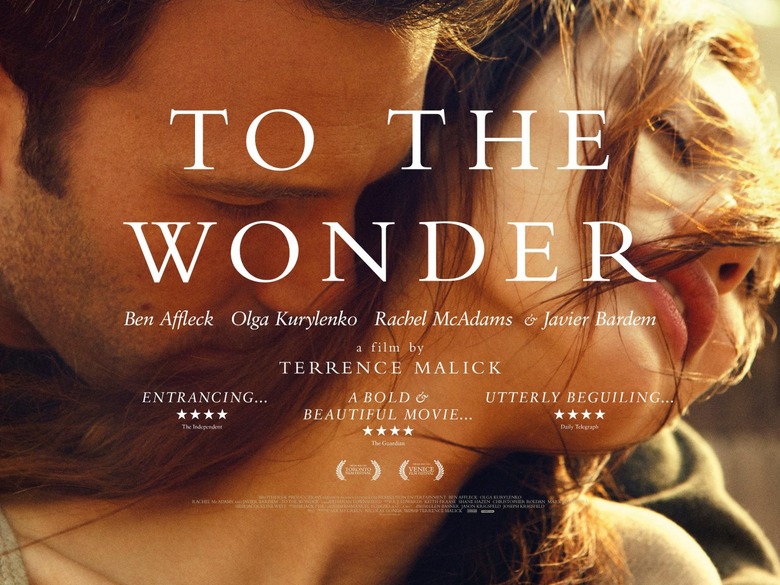

'To The Wonder' Review: Terrence Malick Steps Softly Towards Enlightenment

In the twenty years between Days of Heaven and The Thin Red Line, Terrence Malick was elevated from director who salvaged Days of Heaven only after years of editing, to cinematic messiah. His aesthetic approach was canonized, and actors flocked to work with him, no matter how small the part. Now, with two movies in less than two years (and at least two more on the way) Malick is being brought down to Earth once more. This is a good thing. Once again, he's just a guy who makes movies. Fortunately, he makes movies in a way that is unlike most others, and thanks to his improvisational process he still carries the trust of talented actors.

I'd very much like to love his latest film, To the Wonder. I do appreciate it quite a lot, which is something different. As if designed to be a miniature of his career, this movie describes a tension between the glorious and prosaic. It is not a conventional narrative, but rather a look over Malick's shoulder as he feels his way towards an idea.

That idea is a portrait of our relationship to the divine, as expressed through four interconnected lives that sketch a difficult romantic relationship. Whether that "divine" is God or nature, or some ineffable truth, doesn't really matter. Malick seeks to balance the first brush with wonder and the difficult process of sustaining it though the grind of everyday life.

Olga Kurylenko is Marina, a single mother living in Paris. She meets Neil (Ben Affleck), a kind but taciturn American abroad. The two fall in love. Marina is an exuberant force of life, dancing her way through France. We don't know her, but through her we experience an effervescence. Soon she dances to America in the company of Neil and her daughter.

Life in Neil's native Oklahoma is difficult. The landscape appears only partially finished, like the God of Genesis walked away after five days and never returned. People are broken and lost. Pollution stains the poor. Neil, an environmental inspector, cares in some way for their relationship to the land. Father Quintana (Javier Bardem), as a local priest, should also be caring for the people. But his faith is strained, his church mostly empty, and he can only stare helplessly at suffering.

That Malick is working from a mere seed of an idea is frequently evident. The director often seems to be walking in a circle around the perimeter of a story. The hushed dialogue, when it is present at all, is only texture. Reverent voiceover provides more deliberately scripted development. Marina's interior dialogue says "you brought me back to life," while acknowledging "I know strong feelings make you uneasy." The identity of "you" is assumed to be Neil, but given the general metaphor that ID is open to question.

The narrative structure may seem tentative, even unfinished. At two hours, there is more than enough time for digressions and minor interludes that contribute texture and "feel" — which would be a lot more useful if the entire film wasn't already texture and "feel." And yet Malick builds an effective metaphor in which Affleck's character has a dual nature. Neil is both the man reaching towards something he can't quite define or grasp (his interest in Marina), and the uncommunicative God with whom mankind strives to reconcile.

Don't be put off by the idea of Malick making an explicitly religious film; this is no doctrinal recitation. The human problems experienced by Affleck and Kurylenko in their relationship, and the crisis of faith experienced by Bardem's priest, suggest that an aloof deity is not one with which we can have an easy relationship, or perhaps any at all.

The director hasn't made a film that is so "Malick" as this one. To the Wonder features all the elements we accept as his signatures: patchwork scenes, a reverent yet detached lens, soft light, an eye that is often more interested in an environment than the people in it. The idea that this film could be "too Malick" — a criticism voiced since the film's Venice premiere last year — is the outcome of the codification of his work. In elevating him to a paradigm, we've reduced him to a cliche.

The struggle to align an existence with the divine isn't very cinematic, and To the Wonder is all process, in both form and function. There's a sense of the story forming (or not, some might say) as the film runs. Malick makes movies that reflect the way he makes movies. They're intuitive, driven by emotion rather than storytelling scripture. Irony surfaces here as one idea, repeated in the film, is something the director seemingly resists: the need to focus, and to make choices.

To the Wonder doesn't quite resolve. How could it? There is no answer to the question of our relationship with God. The metaphor can't encompass the experience. There is only a process. Indeed, To the Wonder doesn't get as close as it needs to get for my own satisfaction. It's a conversation rather than a statement. That said, given the chance, I'd eagerly sit down with Malick to have that discussion in person. In the absence of that opportunity I'll accept To the Wonder as a reasonable substitute./Film rating: 6.5 out of 10