Cool Stuff: Screen Epiphanies: Filmmakers On The Films That Inspired Them

I've always loved reading and hearing what great filmmakers think of other great films and directors. You may have noticed that we ask some directors about their favorite films, from time to time, and I've even featured other websites and books that delve into this subject on the site from time to time.

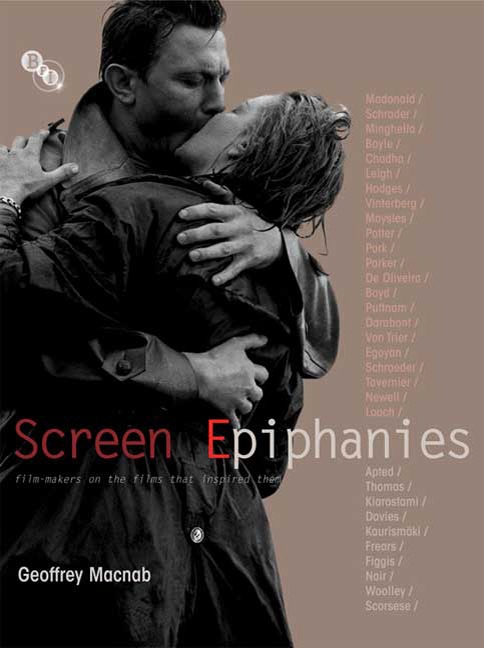

Geoffrey Macnab and the British Film Institute have put together a book titled Screen Epiphanies: Filmmakers on the Films that Inspired Them collecting the stories of thirty-five leading international filmmakers focusing on "the film moments that stayed with them long after they left the movie theater" which inspired them to pursue a career in the movie industry.

Each and every director's 'epiphany' is different and remarkable whether it is the lasting impression made by a single ephemeral moment in a film long forgotten by others; a movie which captured their imagination and inspired them creatively; or the overall magical effect of going to the cinema and the nostalgia of an early film-related experience. With refreshing frankness and clarity some of the directors describe the hurdles they had to overcome because of race, class or gender to break into the movie industry. Films were a support to many, they describe how they identified with the themes growing up and how they were inspired to pursue a filmmaking career. Their experiences of film and film-making styles may differ radically but what stands out from each director's epiphany is their genuine passion and enduring respect for film.

The new 304-page hardcover edition will be released on January 24th 2010, and is available for preorder on Amazon for around $19.

Here are some of the filmmakers / films featured in the book:

Here are a few excerpts that were previously published online:

Danny Boyle / Apocalypse Now: "I had always wanted to be a film director since seeing A Clockwork Orange, but it was in the same way that I wanted to be a train driver. It wasn't practical really. I never went about doing anything about it. I did plays at school and I directed assemblies on stage. Then I went to university and started doing drama. I started directing there properly but I was directing for theatre (not film). When I came to London for a job in the theatre, I was living in a place in Fulham with some mates. They gave me a bedroom to stay in. I was an assistant stage manager, driving the truck, sweeping up and setting up the stages. They were an amazing company called Joint Stock Theatre Company. Outside the flat in Fulham, there was this huge billboard. One day, this black poster went up with Apocalypse Now on it. I am sure I must have known something about it from Time Out or whatever. Anyway, I went to see it. That was the moment when everything suddenly made sense. I guess what it does it that it collides some of the elements of American mainstream cinema from the time and art. That was what Coppola had done in a way. What was interesting about it for me was that I was so transformed by it. My dad came down to stay with me in London. I wanted to take him to see Apocalypse Now. The only place it was on was at the Prince Charles cinema. Then, unlike now, the Prince Charles cinema usually showed porn but they were showing Apocalypse Now. I took him to see it. Before the film began, there were all these trailers for porn. It was so embarrassing sitting there with my dad, watching these quite explicit group-sex orgy films. Then Apocalypse Now began and we sat there. What I remember was trying to persuade him how great it was. It was like trying to persuade him that Led Zeppelin and David Bowie were great artists and wanting him to come on board about it. But in fact I don't remember his response to it at all. Why that's weird is that he fought in the war. He was in the RAF. His friends were killed. He left the RAF because if you stayed in the RAF as what he was – which was a gunner – you basically got killed. You got paid a lot of money. You were very glamorous. You had the best uniform and the girls flocked around you but basically you died quite soon. So he left and transferred into the army, which was what a lot of guys did. It's typical of being that kind of age that I never really asked him what he thought of the film. I tried to convince him what a great film it was but he never spoke about it in that way. There is something that haunts most directors, which is that we don't really do anything useful although we're thought of as being useful. He [my dad] fought in the war and contributed something and yet all I wanted him to do was watch Francis Ford Coppola's version of the war. It didn't undermine the film for me but it categorises film for me in a way. Film often runs in parallel with life and it feeds off it but I don't think it necessarily nurtures it. I don't think it necessarily contributes in the way we think it does. We, in our world, in our bubble that we work in, imagine that it does but I am not sure that it does."Mike Leigh / Room at the Top: "In 1959 in Salford, at the local cinema, I saw Room at the Top. I have a great respect for Jack Clayton (the film's director, whom I actually knew a bit). When I think back on Room at the Top, it was not a great film. When you look at it, it still has pretty ropey, old-fashioned acting and ludicrous casting. The choice of Laurence Harvey! He is as northern and working class as Oscar Wilde himself. But at the time I saw it, at the age of 16 or whatever, the epiphany was watching and experiencing a film that was looking at the real world – which was the very world outside the cinema when I stepped out into the street."Lars von Trier / Barry Lyndon: "Watching Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon is a pleasure, like eating a very good soup. It is very stylised and then suddenly comes some emotion [when the child falls off the horse]. There is not a lot of emotion. There are a lot of moods and some fantastic photography, really like these old paintings. Thank God he didn't have a computer. If he had a computer at that time, you wouldn't care, but you know he has been waiting three weeks for this mountain fog or whatever. It is overwhelming with the boy, because it is suddenly this emotional thing. The character Barry Lyndon is not very emotional. In fact, he is the opposite. He is an opportunist. I saw the film when it came out. I was in my early twenties. The first time I saw it, I slept. It was on too late and it is a very, very long film. What is interesting is that Nicole Kidman told me Kubrick hated long films. If you have seen Barry Lyndon, the last scene of the film, where she is writing out a cheque for him, is extremely long. It goes on and on and on, but it's beautiful. The good thing is that Kubrick always sets his standards. Barry Lyndon to me is a masterpiece. He casts in a very strange way, Kubrick. It is a very strange cast. But that is how the film should be, of course. This thing that he liked short films was very surprising. And he liked Krzysztof Kieslowski very much. He was crazy about Kieslowski. I don't know if Kubrick saw any of my films, but I know Tarkovsky watched the first film I did and hated it! That is how it is supposed to be. The narration in my films Manderlay and Dogville is definitely inspired by Barry Lyndon, and the narration there is this ironical voice, this whole chapter thing, the feeling there are chapters. I have done that in Dogville and Manderlay and to some extent in Breaking the Waves. It is all Kubrick!"Martin Scorsese / The Red Shoes: "I used to call it brushstrokes, the way Michael Powell used the camera in The Red Shoes. Also, the ballet sequence itself was like an encyclopaedia of the history of cinema up to that point. They used every possible means of expression, going back to the earliest days of silent cinema. In the documentary I am making about British cinema, I have to approach it from my point of view, from what I experienced and how I experienced it. It was literally intertwined with American cinema. Watching British film was as natural as watching a Western. We began to understand the different genres of British cinema, whether it was The Blue Lamp, John Ford's Gideon of Scotland Yard, An Inspector Calls or Seth Holt's films, let alone the films by Joseph Losey or Basil Dearden or Ronald Neame. In its very restrained way, Kind Hearts and Coronets was a film that influenced a great deal what I do with voiceover. (But) I keep coming back to The Red Shoes. If I come back from shooting a film at 3am from a night shoot or at dawn and it is on, I find it difficult to go to sleep. It is a film that I continually and obsessively am drawn to. It was hard to see good colour copies of the film. I sought out whatever theatre they were playing in. Eventually, we obtained colour television sets and we saw it at least on colour on TV. The big prize was to get a good 16mm colour print. That was a major coup, to get that or at least to see it. That became a kind of obsessive search."Anthony Minghella / The Blue Angel: "What I remember was that it was the first time a piece of fiction had had such a devastating emotional effect on me. A lot of children remember seeing cartoons, Pinocchio or Bambi or something that breaks their heart. I remember seeing The Blue Angel and it breaking my heart. It was the first time I realised there was an adult world – that adults could damage each other or destroy each other emotionally. It might have fed into a whole series of epiphanies about my own upbringing. I was living in a family where my grandparents had separated in quite complex circumstances. Perhaps it resonated with some elements of that, to do with simply how love can be a rupturing and damaging emotion as well as a healing one. Also, to see somebody who is in an authority position made so small, so diminished, by the feeling of having no control."Thomas Vinterberg / Hearts of Darkness: "In a strange, lethal way, I was suddenly wildly attracted to the process of filmmaking, even though it is described as a nightmare – a matter of horror – in that film. There is a trancelike atmosphere. Suddenly, I was reminded that you can feel like it's a matter of life and death when you make a film. It changed from being a mediocre feeling of emptiness in your life to something that feels necessary. I realised that filmmaking can be many things – and it can be narcotic in a way. You can become addicted to it."Cool Stuff is a daily feature of slashfilm.com. Know of any geekarific creations or cool products which should be featured on Cool Stuff? E-Mail us at orfilms@gmail.com.

via kottke