Political Activists Hid Protest Art In Melrose Place For Over 3 Years

It is not uncommon to happen upon subversive art in the mainstream. You can find the provocative work of R. Crumb, Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe smuggled into the background of films, or, in many cases, outright adapted as a feature (à la Ralph Bakshi's take on Crumb's "Fritz the Cat"). What you don't expect is to throw on a network evening soap opera and notice that a character's pillowcase is adorned with a design pattern of unrolled condoms — especially in the 1990s.

MacArthur "genius grant"-winning artist Mel Chin thought the same thing 30 years ago while teaching art simultaneously at CalTech and the University of Georgia. Inspired by the notion of product placement exploding across movie and television screens all over the world, Chin wondered what would happen if he could sneak a conceptually contentious piece of art into the background of an otherwise apolitical show. Would people notice? Would they at least be subliminally affected? There was only one way to find out.

And, according to a recently published Slate article by Isaac Butler, when he spied "a huge, blond-haired head" framed in front of an innocuous painting, there was only one show through which to conduct his experiment. This is how "Melrose Place" became the covert playground for the GALA Committee, an upstart artist collective consisting of Chin's students from Georgia and Los Angeles (hence the acronym). How Chin got the group's work placed on the hit show for years is a fascinating story in itself, one that is currently proliferating across social media like TikTok. Why it took so long for the powers that be — including the series' ultra-powerful producer Aaron Spelling — to notice their characters were going about their conniving, backstabbing business in a world festooned with AIDS protest art is downright hilarious. Here's how it all went down.

Juxtaposing soap opera shenanigans with the Oklahoma City bombing

According to Butler's piece, Chin's idea was to reverse the function of background art on a television show, turning seemingly mundane props into actual art. The GALA Committee's project, titled "In the Name of the Place," was a brilliant idea. There was just one problem: no one involved in this endeavor had connections to people working on "Melrose Place."

But, hey, who needs an "in" when you've got the white pages?

The far-from-timid Chin cold-called the series' set decorator, Deborah Siegel Cosentino (then credited as Deborah Siegel), who initially ignored him. But he persisted and ultimately won over Cosentino by appealing to her lefty activist conscience. She was all in on the idea and agreed that the insertion of the committee's art should be done clandestinely.

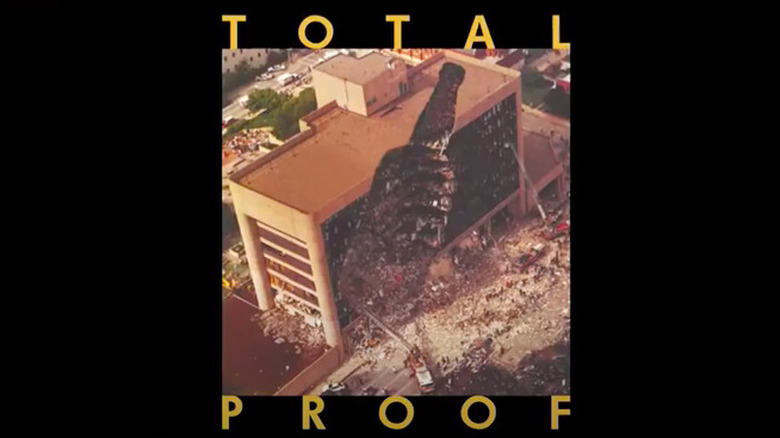

At the outset, Cosentino couldn't provide Chin and his students scripts, so they just pushed the envelope as hard as they could and waited to see if anyone would notice. No one did — at least, not they snuck a remarkably ballsy spoof of an Absolut Vodka ad, sporting the slogan "Total Proof" over the bombed-out Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, onto the air. A line producer caught it, having taken offense, and alerted the show's executive producer, Frank South.

In an incredible stroke of luck, South came to television by way of the experimental theater scene in the TriBeCa neighborhood of New York City. He wasn't mad. In fact, he was thrilled. So he joined the mischievous conspiracy, and began supplying the collective with scripts so they could tailor their creations to each episode's narrative.

What about Spelling? "I always intended to tell Aaron about it," South told Butler. "But at one point, I decided not to, because it was getting so integral. You know: Apologize, don't ask permission."

So how did Spelling find out?

The wrath (or lack thereof) of Aaron Spelling

In 1997, Los Angeles' Museum of Contemporary Art's then curator, Julie Lazar, decided to feature the GALA Committee's art in a program called "Uncommon Sense." This was a meta exploration of the exhibition process itself and Lazar believed what Chin had sneakily accomplished within the parameters of a glitzy, shamelessly silly soap opera belonged in this show. So, all of the work they'd smuggled into "Melrose Place" — including Chinese food bags protesting the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, a blown-up illustration of RU-486's chemical structure (aka "the abortion pill") and David Hockney-esque landscape paintings of notorious Los Angeles locations like the Viper Room (where River Phoenix died) and 10050 Cielo Drive (where Sharon Tate and friends were murdered by members of the Manson Family) — was on display to the public.

They'd outed themselves to the world and, obviously, Spelling. So, when the powerful producer read a piece about the show in The New Yorker, he called South to his office. When asked when he'd planned on telling Spelling about the GALA Committee's work, South replied, "I figured about as late as possible." South stuck with the show until 1998. He subsequently worked on "Baywatch" for a season before becoming an author.

As for the GALA Committee's legacy, that this actually went down is news to me. According to Butler, he doesn't know anyone who noticed the artwork while watching the show contemporaneously. Does this mean Chin's project was a failure? Not at all. I think getting away with it for as long as he did is, if nothing else, one of the greatest unheralded pranks in television history. Does this mean I'm going to revisit "Melrose Place," a show I actively despised at the time, all these years later. No. No, it does not.