David Fincher, Director Of Fight Club, Still Not A Fan Of People Who Like Fight Club

David Fincher's 1999 film "Fight Club" may be one of the most widely misinterpreted films of all time.

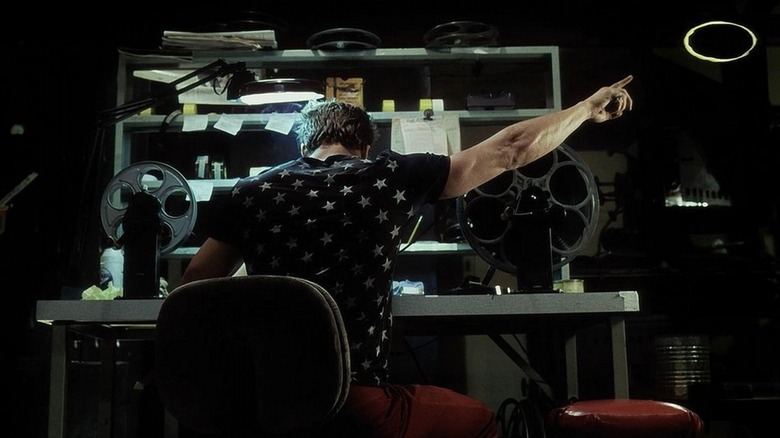

"Fight Club" follows a nameless office wonk (Edward Norton) who finds that modern life is sapping him of his passions and forcing him to become a mindless consumer. He eventually achieves catharsis in under the tutelage of the ultra-cool Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), a devil-may-care soap salesman who espouses an ultra-masculine philosophy of strength through personal violence. He and the Norton character begin hosting underground bare-knuckle fight clubs with other equally pathetic men seeking to assert their masculinity. A lot of knuckles are skinned, eyes damaged, and bruises inflicted.

Eventually, Tyler has formed a cult of put-upon middle-class white service workers who begin tainting customers' food and committing city-wide acts of vandalism as a form of punk rock defiance. But then, a line is crossed. Tyler's cult turns to military-like tactics and bomb-making. The cult members happily sacrifice their identities. Tyler gives apocalyptic speeches about how masculinity can only thrive in a wild world of ruination. "Fight Club" argues that masculine assertions of violence are tantamount to the end of the world.

There are still people, however, who feel that Tyler is a heroic figure. In recent years, "Fight Club," and Tyler in particular, have provided a lot of talking points for an online community of incels and members of far-right Nazi groups as positive expressions of their dark, sexist frustrations. Some audiences seem to take the film's slick coolness as an endorsement of Tyler's philosophies and see his apocalyptic, ultra-masculine visions as aspirational.

Fincher, in a recent interview with The Guardian, washes his hands of the matter. The director said he can't really help if so many people have so grossly misinterpreted his film.

Tyler Durden is not a hero

"In the world I see," Tyler says in the film's most important speech, "you are stalking elk through the damp canyon forests around the ruins of Rockefeller Center. You'll wear leather clothes that will last you the rest of your life. You'll climb the wrist-thick kudzu vines that wrap the Sears Tower. And when you look down, you'll see tiny figures pounding corn, laying strips of venison on the empty carpool lane of some abandoned superhighway." Tyler wants nothing less than a return to an agrarian society.

It doesn't take a very sophisticated audience member to see "Fight Club" as a condemnation of ultra-masculine violence as a cathartic release. In the film's early fight scenes, the punches and bruises do indeed provide Tyler and the Edward Norton character with the outlet they need to express their frustration, but it's easy to understand that nihilistic destruction cannot be brought to any kind of logical conclusion beyond the apocalypse. There is, of course, a dark working-class fantasy in the film's final scenes — when Norton witnesses the destruction of multiple banks and credit card companies — but Tyler's means are twisted and incorrect.

In The Guardian piece, David Fincher seems exasperated by the far-right interpretation of his work. Eventually, however, he just had to step away, saying:

"I'm not responsible for how people interpret things [...] Language evolves. Symbols evolve. [...] OK, fine. It's one of many touchstones in [far right] lexicography."

When asked how he felt about that, Fincher said:

"We didn't make it for them, but people will see what they're going to see in a Norman Rockwell painting, or Guernica."

Incidentally, Artsper Magazine did a great, brief rundown on Guernica for their website in 2019.

'I don't know how to help them.'

David Fincher continued with his frustration, saying:

"It's impossible for me to imagine that people don't understand that Tyler Durden is a negative influence. [...] People who can't understand that, I don't know how to respond and I don't know how to help them."

It's entirely possible that many audiences merely respond to Tyler's blustering self-assurance and physical strength. Sometimes confidence, mockery of the system, and something akin to charisma are going to be seen as positive qualities, no matter how horrible, racist, violent, or dumb the speaker. See also: Alex DeLarge in "A Clockwork Orange," or Tony Montana in Brian De Palma's "Scarface." While these are all good movies, it would be wise to look at people who own "Fight Club" posters with a modicum of suspicion.

This is a fight Fincher has been fighting for many years. In a Variety article from 2014, Fincher was already addressing the far-right wonks and media-illiterate weirdos who were lionizing Tyler Durden. Quoted speaking at a San Diego Comic-Con panel, Fincher said:

"'Fight Club' is about moving through a modern disconnected society. It's a satire. Many don't get that. [...] My daughter had a friend named Max. She told me 'Fight Club' is his favorite movie. [...] I told her never to talk to Max again."

"Fight Club" was released in 1999, the same year as "American Beauty," and clearly America was wrestling with Millennial angst and disaffection. Despite a world without war and economic good times, a lot of literature and art of the era were focused on America losing its soul, its passion, and its ability to make art without giving into crass commercialization and the bottomless ennui of suburban comfort. "Fight Club" speaks to that.

It's not a commercial for fight clubs.