'Silence Builds Tension': An Oral History Of Mission: Impossible's Iconic CIA Heist Scene

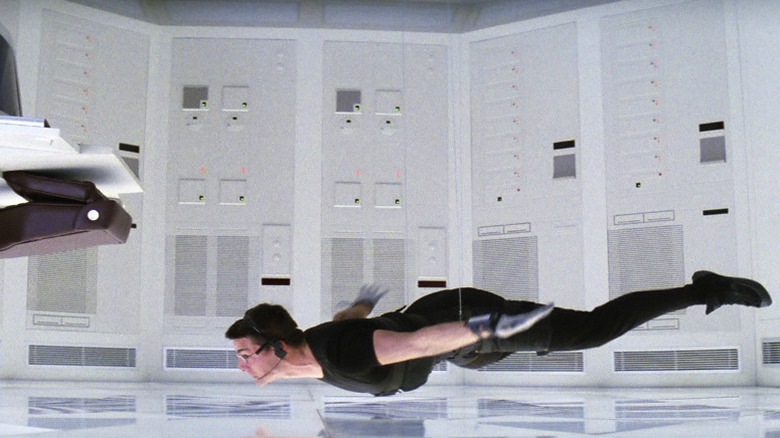

Long before Tom Cruise performed jaw-dropping stunts like scaling the world's tallest building, strapping himself to a plane as it took off, or hanging underneath a flying helicopter as IMF agent Ethan Hunt, the "Mission: Impossible" franchise's first seemingly impossible mission required him to not make a single sound.

As the first "Mission: Impossible" was filming in 1995, movies like Michael Bay's "Bad Boys," John McTiernan's "Die Hard with a Vengeance," and Robert Rodriguez's "Desperado" were blowing up at the box office. And while "Mission: Impossible" would eventually have its fair share of explosive action (including a climactic moment in which a helicopter follows a train into a tunnel), director Brian De Palma also wanted to create a set piece that was the opposite of the brash, loud spectacles audiences expected from a summer blockbuster.

The result: A nearly 20-minute heist scene in which Ethan Hunt, Claire Phelps (Emmanuelle Béart), Luther Stickell (Ving Rhames), and Franz Krieger (Jean Reno) orchestrate an elaborate theft from a highly secure terminal located inside CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

The room's floor? Pressure sensitive. Its air? Temperature-regulated. And perhaps most importantly, any noise above a whisper would trigger the alarm, giving De Palma a narrative reason to embrace quiet while so many of his contemporaries were cranking up the volume.

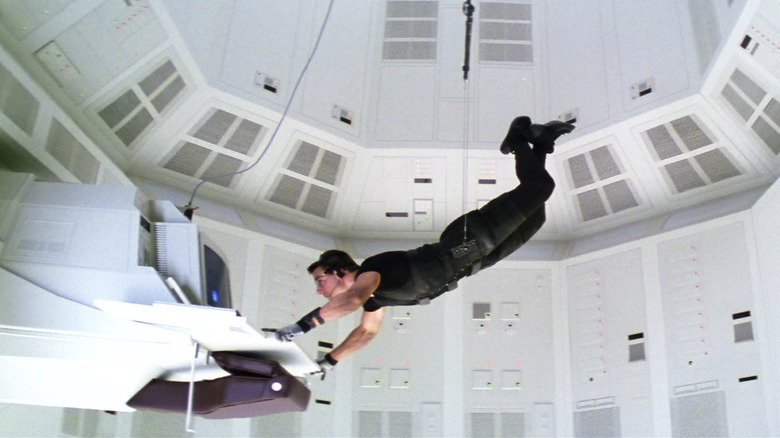

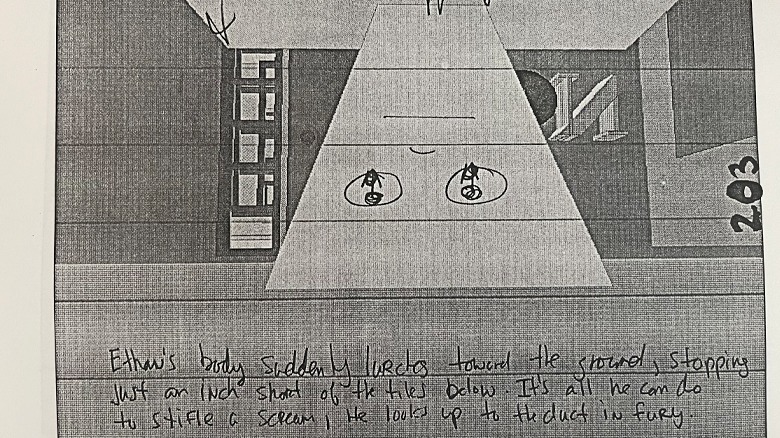

The solution, of course, involved one of the signature stunts of the entire franchise. With Claire incapacitating CIA agent William Donloe (Rolf Saxon) and Luther remotely tracking Donloe's location from a fire truck outside, Ethan is lowered toward the computer by ropes, only to be unexpectedly dropped by Krieger and quickly caught again, now only millimeters from the floor, splaying out his limbs to maintain his balance without touching anything.

Here's how the scene came together, as explained by the people who made it.

Preparing the set

JC Calciano (Production Associate to Paula Wagner): Honestly, I don't think anyone knows this. I think that five of us who were in this meeting ... I truly don't think anyone else outside of this meeting even knows this. When we were writing the script, we brought in a friend of mine. I had produced a movie in Arizona, and I met this woman who was a CIA agent. She and her husband were both CIA agents. So I brought her in as a consultant to help with the movie. Her name is Sue Doucette, and she came to London to help us as a consultant.

When we were working on the script and talking about the script, she told us that — and this is true — the CIA had a room that was ... I think there was a name for it, but I don't remember. There was no outside connections into this room. So this way, nobody could get to it. This particular room was the most secure room at the CIA. The only way you can get in is by one door with one agent. We wrote this scene based on her notes and experiences on that. She was so great, and she was so helpful. We hired her to be the actress who stands guard at the door for that scene.

David Koepp (Screenwriter, from an appearance on the Script Apart podcast): We'd had the big idea of the NOC list, which some person we were doing research with, an advisor, she referred offhandedly to something called the NOC list, and we said, "Wait, what's that?" because it had a great name. She said, "Non-official cover agents. It's a list of everyone that's undercover." I said, "Well, that seems like a terrible thing to put in a list that anyone could get." And she said, "Oh yes, it's very well-guarded." We were kicking each other under the table, because if that's not a MacGuffin, I don't know what is.

JC Calciano: Norman Reynolds was the art director. So we were talking about this particular room, and Norman said to Sue, "Okay, well, I have to build this room. So what does this room look like, and what should it look like?" Now, I think if I remember correctly, she never had access to it, so I don't think she had clearance of the room. So she didn't know. So we sat there, and we were like, "Well, okay. What are we going to make the room look like?"

David Koepp: I said, "What if the floor lights up like that Michael Jackson video?"

JC Calciano: I said to Norman, "Well, you art directed 'Star Wars.'" He said, "Yeah." I said, "So do the Death Star." He loved the idea. So he says, "I've got all this 'Star Wars' stuff." I don't know whether he [was allowed to use it], or now I'm going to get in trouble with George Lucas, but that room is the Death Star. I don't know if that's a known thing. If you look at it, it looks just like the Death Star. So that was a cool little thing that I think that a lot of people don't know.

Chris Soldo (First Assistant Director): I think it suggested [in the script] that the setup was to be that if somebody entered the room where the feet touched the ground, the panels were going to light up. That's not the way it was shot, however. The original concept, and what was prepared, was an even floor, but if you step on a panel, that even floor goes to red if there's contact with the panels. Well, on the first day we shot, Brian came in, he must have been thinking about this. And he said to Steve Burum, the cameraman, he said, "We're going to make a change here. The floor has to either be activated or not activated." Which meant that he wanted a very strong visual of, either the floor is lit up or the floor is dark.

Now, that wasn't rigged, that wasn't prepared for. So we're on this set and all of a sudden the crew, the DP and electrical, in conjunction with the art department, had to completely revise the language of what the floor was saying. The art department, they did some tests right on the spot with neutral density filters, like soft gel, to get the right amount of darkening of the lit floor. And they literally had to, on the day of, get the lighting company to cut new hard plastic gels to go in that floor. So we had this huge delay on the day. Why? Because Brian had decided he didn't want the storytelling to be, you walk on the floor, the tiles turn red. He wanted it to be, when you arm the floor, when it's locked, there's a huge visual change in the way the floor looks.

JC Calciano: People who build the set sometimes don't read the scripts. So we were all ready to shoot, and I show up to set either that morning or the day before, I don't remember, and they show us the set, like, "Oh, there's the set." I remember looking at the set, and there's this really beautiful, state of the art office chair at the console. I was like, "Did anybody read the script?" They're like, "Yeah, no." I'm like, "Well, the floor is sensitive, so we can't have a chair on the floor, because it's going to trigger the alarms." Then they were like, "Oh my God." No one thought of that at the time when we were designing it. So we had to scramble to build a seat that was not on the floor, because the floor was the thing that would set off the alarm. [They] were like, "Oh, s***. You're right," because they were just building this desk ... and I guess no one put two and two together. Then we were scrambling to build this chair, which was fun.

Paul Hirsch (Editor): One of the doors in the corridor said something about "Authorised Personnel Only," and it was spelled with an "s" because we were shooting in England ... I pointed it out, and they had to re-shoot it the next day with a Z, because the CIA would not have spelled it with an S.

JC Calciano: I got the script, and I said, "Well, I have a problem with the fact that" — I think they set off a fake fire alarm in Langley, and the firemen have to come. I'm like, "Look, I've never been to the CIA. I don't know, but I could tell you this: If a fire alarm or an alarm or something goes off in Langley, more than three firemen show up to put this thing out." It just seemed really silly to me, like, "Oh, okay. Now the CIA has a fire or an alarm, and we're going to send three guys." Then not only did they send three guys, but the day that we were shooting, and this is 1995, there was an old fire truck. In the movie, you really don't see it, because we were really tight, but it's an old fire truck. So not only are three people responding to a fire at the CIA, but they're showing up in this janky old fire truck.

I said to Norman, "It's 1995. We need a state-of-the-art fire truck, or whatever is in Washington, DC at the time, because this is not what they use in Washington, DC." I remember Norman saying, "Well, we're an hour outside of London in the UK. If you can get me a current fire truck in the next two hours, an hour outside of London, we'll use it. This is what we got, and this is what I'm going to shoot." So we did, and that always just sat with me — every time I watch the movie, I cringe a little bit at three people responding to a fire in an old fire truck at the CIA.

Keith Campbell (Stunt Double, Tom Cruise): Cruise comes in as somebody else. Ethan, his character, comes into the CIA as a fireman, as a different person, and then he rips off the mask in this utility room. Well, I [played] the different person. He breaks in, we're on the fire truck, we run in the building, I go up to the counter and I don't think I say anything ... and then we take off running and go into that [side] room, and I think Tom kicks somebody.

Establishing the stakes

Chris Soldo: We started this sequence on day 66, if I'm looking at the right call sheet, and we had just come off of 30 days of shooting the top of the train. We went right from that into this sequence. By the time we went to this sequence, all of the beats, all of the steps had been worked out.

David Koepp: [De Palma's] other big idea was, "I'm tired of all these summer movies that are so noisy. I want to do a great big set piece in the middle of a summer movie that's quiet." And he did, and did a brilliant job.

Paula Wagner (Producer): There were so many action films at the time and the action films were loud. This concept was about silence. As a director, Brian De Palma was the master of suspense and was masterful at answering this question: What challenge could you find to make a task nearly impossible?

Paul Hirsch: The situation is set up in advance. You can't make any sound, you can't let anything hit the floor. The temperature can't go above a certain amount, and we have to keep [CIA agent William] Donloe out of the room. And so all the elements were set up.

Rolf Saxon (Actor, "William Donloe"): This was, aside from one line, a non-speaking part. In fact, I almost didn't do the job because I had been offered something else that was much better, or so I thought. But once all of that stuff was worked out, that was no problem. It was great. But I was basically a glorified extra on that film. No disrespect to anybody at all, but I didn't have a lot [to do].

Paula Wagner: The tasks were monumental, and it really was Brian and Tom coming up with ideas and inspiration for the movie. We watched so many movies and did such extensive research.

Chris Soldo: I referred to ["Topkapi"] in talking to Brian, maybe to show off a little bit that I knew the derivation of the scene. I said something about, "Well, we'll do 'Topkapi' and then we'll do something else." And he knew that I knew that's where the derivation was.

David Koepp: [De Palma] wanted to do the "Topkapi" thing of coming down from the ceiling, so I said, "OK, let's make the floor so you can't [touch] it," which then naturally suggests the sweat, and Brian said, "Let's just keep piling one sensor on top of the other. The temperature can't go up. There's going to be a rat in the [vent]."

Paul Hirsch: There was a scene in a movie called "Rififi," a French thriller, where they break into — it's a heist movie and they break into a neighboring office. It's either through the floor or through the wall, I forget. But it's all about being quiet and there's no music in the sequence. And that inspired our approach to finishing the scene, no music. And what it showed was that people think that music builds tension, but in fact, silence is an effect also. And silence builds tension.

One of the great suspense sequences of all time is "North by Northwest," Cary Grant in the cornfield attacked by the crop duster. There's no music in that whole sequence. Everybody thinks, "Oh, Bernard Herrmann wrote this great score, and the music for that sequence is fantastic." Well, there is no music in that sequence. And the sequence ends with the plane crashing into an oil tanker on the road, bursting into flame, and that's where he introduces the music. So silence builds tension, and it's an important lesson.

Accomplishing the impossible

Paula Wagner: I just remember standing there and being terrified [laughs] and understanding that this had to be manually done. It had a ballet-like precision, and everything about it — the timing of it, the timing of the visual, the timing of him dropping — all of that had to be absolutely precise. It's art and science working together at the highest level, that all of these things have to be so meticulously calibrated. Rhythm and timing. How long does it take? Mathematics comes into it. What is the drop? How many feet? How many inches? And how fast can you go at a certain speed? I mean, you don't just get up there and do it. And Tom was extraordinary and deeply involved in all the planning and execution of this highly complicated and very daring sequence.

JC Calciano: Everything was done with just pulleys and ropes and stuff. There was no mechanical anything when it came to that. It was also London. It wasn't as techy. We were in Pinewood, and Pinewood is a very old school studio. So it wasn't the high-tech thing that you would think it is, especially being "Mission: Impossible." It was really just in hangars over in Pinewood, this old, classic English studio.

Rolf Saxon: It took about three days to film, surprisingly. Tom insisted on doing most of the stunt himself, and the stunt double came in when they were lighting or they were trying to figure stuff out. But all the time they were literally filming the scene in that room, whenever I was involved, he was always up in that rig.

Keith Campbell: That's the first time I worked over in London, and at that time, it was the special effects guys that were [pulling the ropes]. It was a manual up and down thing. With counterweight, so it's not like it was hard — it was a very nice system, well thought-out. And as the stunt department and as his doubles, we'd go in and work out it from beginning to end and then we'd do a show-and-tell with Tom and De Palma and they may give notes and say, "Hey, can we do this? Can we do this?" So we do that until it's all figured out so Tom doesn't have to waste so much time doing it himself ... He wants to know what's happening. But he also comes to watch so he knows. This [stunt], it was something that we could talk about as he's watching me doing it. I'm saying, "Oh, here's what I do to try and balance this way."

Paul Hirsch: The idea was to keep it as quiet as possible. This is an incredibly difficult chore for the sound editors, who can't stand silence — it just drives them crazy. And there was a closeup of the rope going over a little wheel, and they put in a tiny little squeak, and we had to say, "No, take it out, take it out. They wouldn't go in there with a squeaky wheel. This is 'Mission: Impossible!' They get it right." So we tried taking everything away, and that just didn't quite work. So there's a little bit of air going on.

And then of course, there's the wonderful, what in England they call "footsteps," and in America, we call "foley." I guess it's named after some guy who pioneered footsteps in the industry here. So we used to joke about the rat foley, these little claws on the sheet metal of the air conditioning duct. There's very little going on from a sound standpoint.

Paula Wagner: We had to have little rats when Jean Reno was climbing through the vents. There was a great moment with the rat. We had to get little stunt rats [laughs] and set that up.

Paul Hirsch: Reno drops [Cruise] in order to strangle the rat, which we choose not to show. We made a point not to deal with what he did to the rat.

JC Calciano: I remember I was there for the vents, when he's climbing through the vents, thinking, "Not another f***ing movie where people climb through vents, because could we be a little more clever than climbing through vents? But all right."

Paula Wagner: In my recollection, it took a long time because it had to be done very carefully and it was very dangerous. At one point, I think that the rope went too far down, and he's doing the whole thing himself. You can't stay upside down for very long. So, it had to be done consistently over a period of time, with a lot of starts and stops. Things that seem the simplest are oftentimes the most complex.

Tom Cruise (Producer/Actor, "Ethan Hunt," interviewed in a 25th anniversary featurette): You look at that shot, I'm going from the computer to the floor, and I remember we were running out of time. I went down to the floor, and I kept hitting my face. Kept — bam! — hitting my face, and the take didn't work. And we were running out of time. We had a lot we had to do. So I went up to the stunt guys and I said, "Give me coins." Here in England, they have pound coins. So I put the pound coins in [my shoes] and I hung on the cables to see [if I was] level.

Paula Wagner: This sequence had so much emotional and physical stress that it was really hard for Tom to hang upside down for such a long time. The shooting of it was challenging. It was a lot more difficult than you could imagine, because the key elements in it were real, not digitally enhanced.

Keith Campbell: This was a very fun one to do for me, and for him to figure out how to find his balance point because it's different for every human. And I would turn upside down on the wires and shimmy one way, or if I was too top-heavy, I would just try and be up and down, straight up and down and just shimmy in the harness a little, try and make it move a little bit, because everything has to be really tight.

Paula Wagner: Tom Cruise was exceptional in creating the terror for the audience, the same terror he was experiencing. Imagine hanging upside down and being slowly lowered from the ceiling and almost to the floor and not a sound could be made. Imagine if the person hanging upside down was dropped! And there were some close calls. I mean, it was really tricky. As a producer, watching this being filmed, I was on edge. I was experiencing what the audience was going to experience, which was, "Oh my God, is he going to make this? Yes, it's Tom Cruise, but could something happen?"

Tom Cruise: Brian was like, "One more, and I'm going to have to cut into it and [edit the scene a different way]," and I said, "I can do it." It was also very physical, like straining [when] I'm doing it. So I went down, started at the computer, went all the way down. Beautiful set. De Palma has amazing taste. Went down on the floor and I didn't touch, and I remember I was there, I was like, "Oh my gosh, I didn't touch." And I was holding it, holding it, holding it, holding it, and I'm sweating and I'm sweating. And he just keeps rolling. And I just realize [laughs], Brian is like, working it. He's like, "We did it, we did it, we did it." Like, I am not going to stop. And I just hear him off camera, and he's got a very distinct laugh ... I could just hear him start to howl. And he goes, "All right. Cut." [laughs]

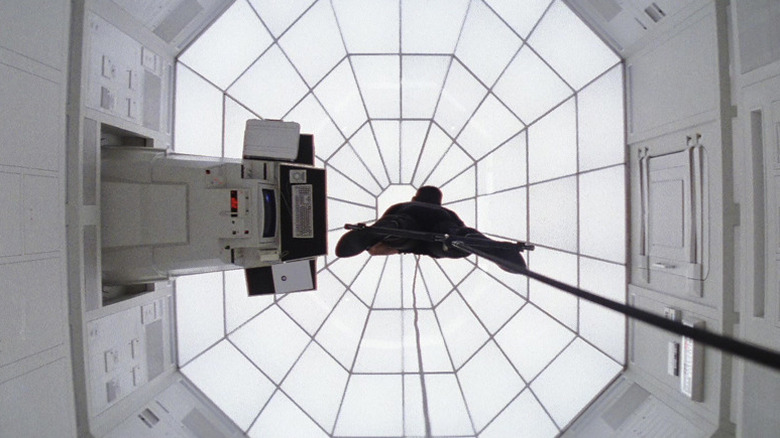

Paul Hirsch: There's a shot of Cruise seen from above, silhouetted against the floor, and the floor is designed to look like a spider's web, and he's hanging in the middle of this like a spider on a thread, and he's as exposed as a bug in a bathtub. He is black against white, and he couldn't be more visible and obvious in this set. And I thought that was quite wonderful.

Chris Soldo: There was the sound stage floor, where all the technicians were standing. This is Stage A at Pinewood Studios. And the set was built elevated off the ground for a number of reasons, but not the least of which was they had to get lighting underneath the little panels. So it was raised off the ground. So we were standing on the ground where we're looking at a slight angle up towards the set ... when we did the successful take where he fell and kept his balance, it just was breathtaking that it happened and that he pulled that off.

Paula Wagner: It was high pressure and really dangerous, and Tom has always handled it like an absolute pro. It truly was nearly impossible. It required absolute precision timing and execution and almost super strength and dexterity from Tom, and trust in the ones who were controlling from above.

Paul Hirsch: The sequence was much longer than it turned out to be, and the trick was — all the elements were there, everything was available. It was just a question of putting it together and looking at it and saying ... it's the usual editorial process. You look at it and you say, "Well, what's wrong with this picture? This is taking too long. This is confusing. This should happen faster. This should happen slower. This is unclear. We don't need this. This is in the wrong place." And you keep making adjustments until you finally get it to the point where you say, "Okay, I think it's right now."

Chris Soldo: In my memory, he held that balancing act for much longer than what's in the film. In other words, in the film, they cut away from him after some point. I don't know what the next cut is from a wide shot. They cut away. But my recollection was, and what was amazing was, that he was in the down position and still adjusting. Maybe the editor thought it disrupted the pace, but to me that was the most amazing thing was that he was down, he didn't hit the ground, and then he maintained it for what felt like forever. Paul Hirsch, who's the editor, who's a friend of mine, I never asked him, but if I recall correctly, he could have held on that shot much longer and didn't.

Paul Hirsch: I thought it was the perfect length.

'You set the suspense hook, and you milk it for as long as humanly possible'

Chris Soldo: You'll recall that Emmanuelle Béart puts the little speck on the CIA agent's [back], and that was something that the guys in the truck could look at. Well, [editor] Paul [Hirsch] lamented later, he said, "I thought of something after the fact and I wish I had thought about it at the time and whispered in Brian's ear. We could have had an extra element where that little flaky thing fell off and the guys in the truck were actually getting the wrong read of where he was, and only the audience knew where Rolf [Saxon's character] really was." Because the guys in truck are saying, "He's still in the bathroom. He's still in the bathroom." But we see him coming out.

I don't know if Brian would've said, "Yes, let's do it," or he might've said, "No, we got enough going on." I don't know. But there was always an effort to take the threads of the tension and milk them as much as you can. So you get that spine tingling cross-cutting of, how is this going to play out? Yeah, so Paul told me later, he said, "I blew it. I thought of this after I saw the dailies and it's too late."

Paula Wagner: As a director, Brian De Palma was really great at creating tension and suspense, because it's all about the setup, and he was masterful at setting up the task and then creating obstacle after obstacle. So the threat had to be taken out of commission. I mean, this is beautiful teamwork on the part of Tom's team. This had to be so carefully orchestrated, so at the right moment, at the exact time, with the right dose, [Claire] had to put the drop in his coffee.

Rolf Saxon: As with most of what I did there, it was incredibly technical. [Brian] wanted everything just right. I remember that crane shot. I don't remember how often that was done. But I remember going to get that laser in my eye was, like, seven times.

Paula Wagner: Then Brian keeps the suspense going. You see [Donloe] walking down to the room, you intercut and see the difficulty of the task that had to be accomplished coming into that room, not making a sound and successfully downloading the information and getting out of there quickly. And then just at that moment, you say, "Oh my God, he is going to come in and find [Ethan]. What's going to happen?" And just at that moment, [Donloe] feels sick.

David Koepp: This is a direct quote from Brian: "You set the suspense hook, and you milk it as long as humanly possible." And that's what we did.

Chris Soldo: I remember on the extreme closeups of the thing going on [Donloe's] coat, the macro lens was so tight that we had trouble keeping even part of his jacket in focus with the speck.

Rolf Saxon: I was on it for, I think, two weeks, and I was working on [another] picture interspersed with that. I was being taken from one set to the other set, so I worked three weeks solid without a day off. That was great. Not complaining. I loved it. It was fun. But I got a little punch-drunk every once in a while, and I was messing around on set, joking around. The first [assistant director], Chris Soldo, came over and said, "Brian wants to have a word with you." And the look on his face was not good. I thought, "Oh jeez, here we go." [Brian] asked me to come over, I came over, and he said, "You're something of a clown, aren't you? A bit of a clown." Chris had said, "Look at me, and if I shake my head no, don't answer." He was standing behind Brian, and Chris and Brian had worked together for 10 years. Chris is a great guy. We're still friends.

So basically, there was a little bit of back and forth, and [Brian] said, "Can you do that again?" And I said, "I beg your pardon?" And he said, "Can you do that again? Make people laugh like that? Everybody was laughing, and I'd like to put that in the show." And I said, "Yeah, sure!" He said, "OK, after lunch, we'll spend a couple hours and put some funny stuff in." So after lunch, we spent all that afternoon and part of the next morning putting in a bunch of stuff, almost none of it which is still there. But the throwing up is. He said, "Do you want noise to happen?" Brian asked if I wanted noise in the bucket. I said, "No, I think they'll get the idea. My thinking is we don't want to gross people out, we want it to be sort of amusing." And he said, "OK, cool. Fine. Fine. That's great. Good idea," as he turned away.

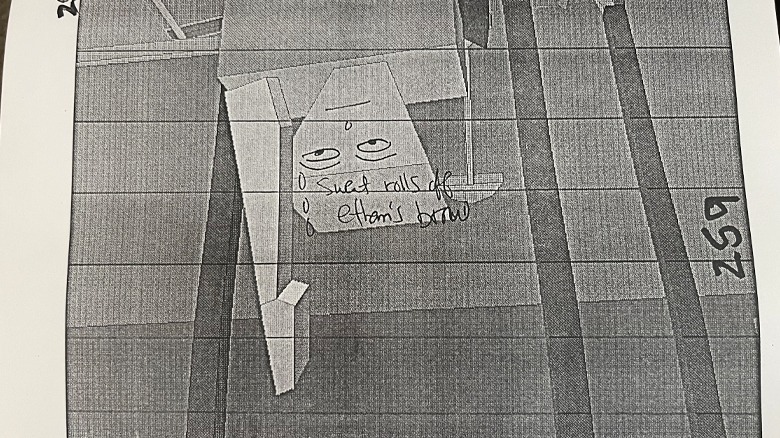

Paula Wagner: Then there is that beautiful shot of the particle of sweat running down [Ethan's] face. There's always something unexpected that happens in the well-planned mission, and that contributes to the tension. And the audience is then on the edge of their seats.

Paul Hirsch: When he's hanging there inches above the floor, then you see the sweat coming across the lens of his glasses, and then when he catches it with his hand, I thought to myself — I remember thinking this at the time — to catch that drop of sweat in the palm of his hand would've been incredibly destabilizing. I mean, he's balanced so carefully. But we played it in closeups, so you don't question it. We don't show his whole figure at that moment, but to me, that's a kind of a weakness. But I guess we got away with it.

Chris Soldo: The closeup of the catching of the drop, that was done by a second unit. Brian's protege, second unit director Eric Schwab, who did all of the plate photography in Ireland for the train sequence. That was one of the shots that was handed off to him.

Keith Campbell: Catching the drop of sweat from the glasses, that was fun. I got to do that. That's actually my hand in there. But this camera was shooting 360 frames per second and it makes so much noise. I mean, I think you get one take for a roll of film on that because it's just going through so fast. I know I wasn't hanging in wires when we did the actual high-speed camera and the sweat dropping because it was such a closeup on the drop of sweat coming down and the hand coming in to catch it.

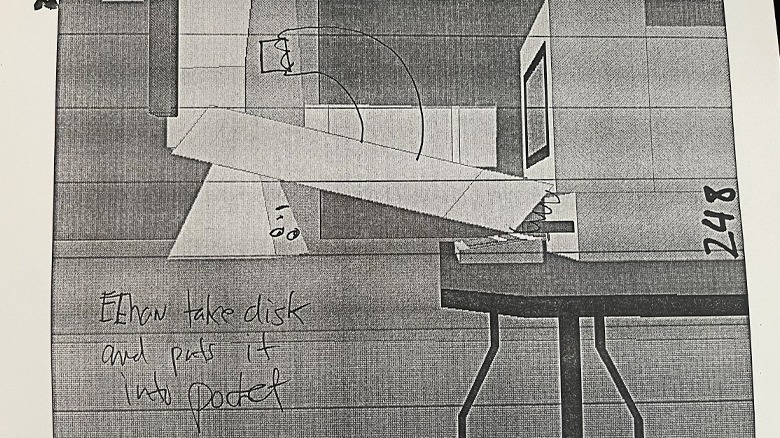

Paul Hirsch: [The knife falling is] an "Oh my God" moment, because you think they've gotten away with it, and [Reno] takes the disc from Cruise and drops the knife and they look at each other like, "Oh, s***." But that closeup of the knife falling and twisting is not a real knife. It's all CG.

Chris Soldo: I think [the knife moment is] typical of the way that Brian works. He's got something, and then the night before, he doesn't sleep and he's thinking about all sorts of things. I just think he loves to have overlapping tension, being able to cut to various places. And having the rope, having Tom, having the element of time and the slow download, having the CIA agent walking around eating and throwing up — he loves to play with holding those elements of tension and milking them, basically. I think the knife thing might have been something that was literally, that might have been something that was figured out or decided at the 11th hour.

Paula Wagner: There was something very specific and intimate about this sequence. It's almost the polar opposite of big, high, wide, loud sequences.

Script pages and Brian De Palma's storyboards

Allow me to interrupt the oral history format for a moment to share some images with you.

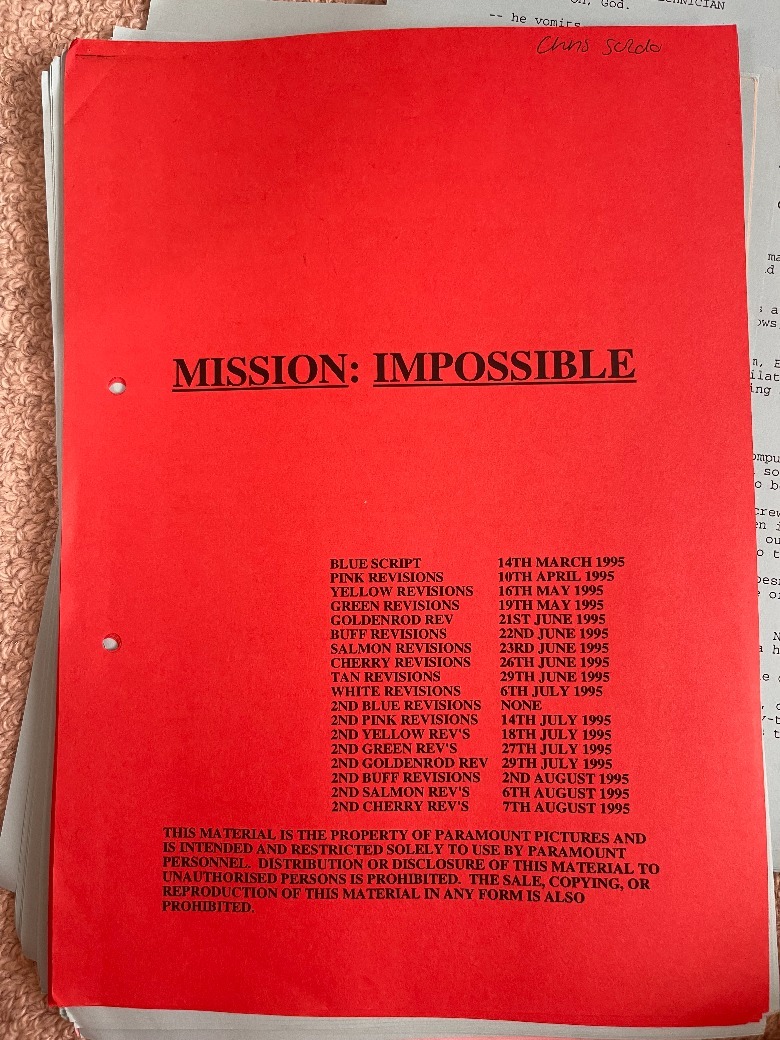

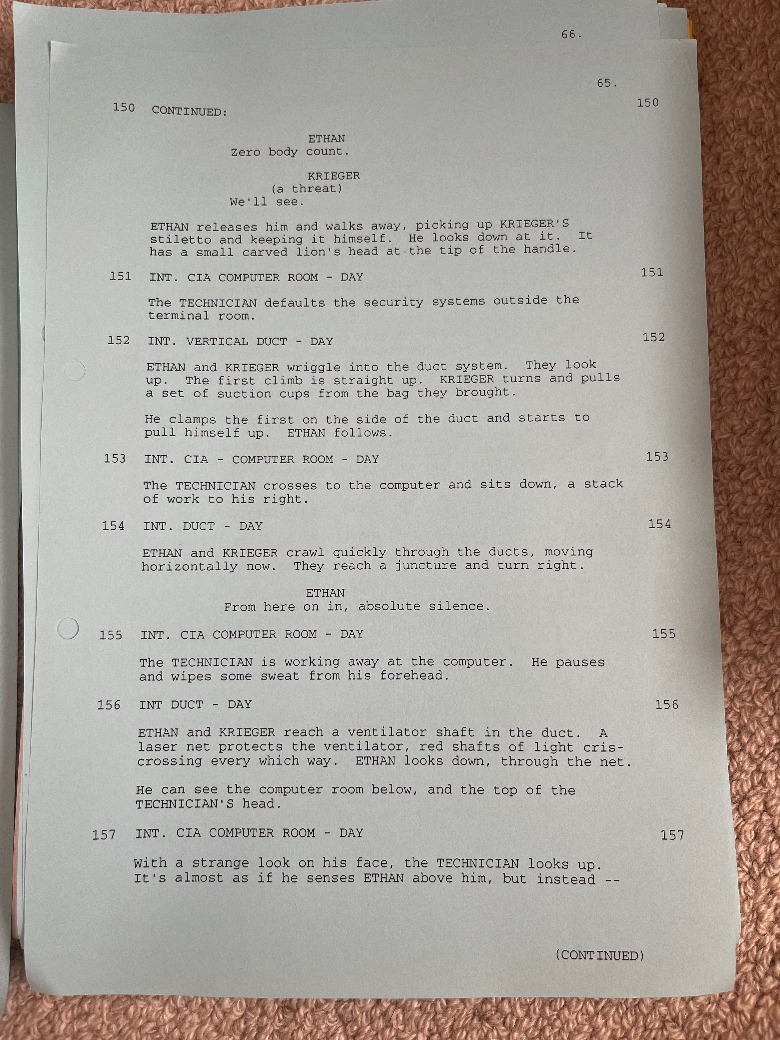

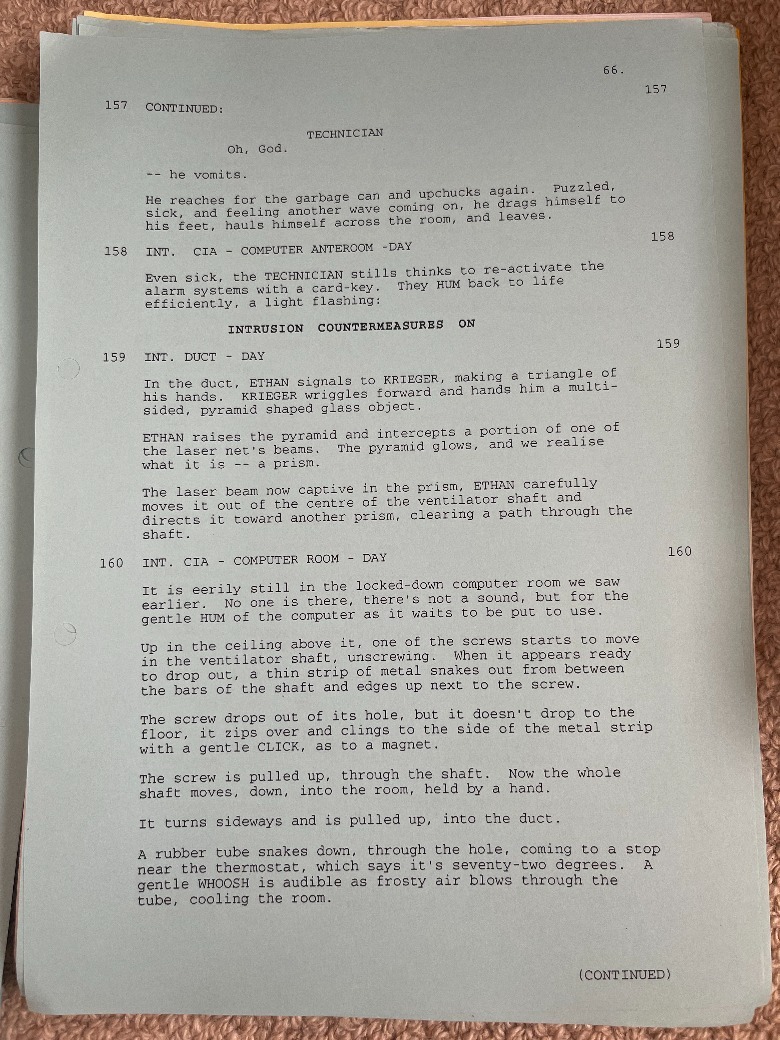

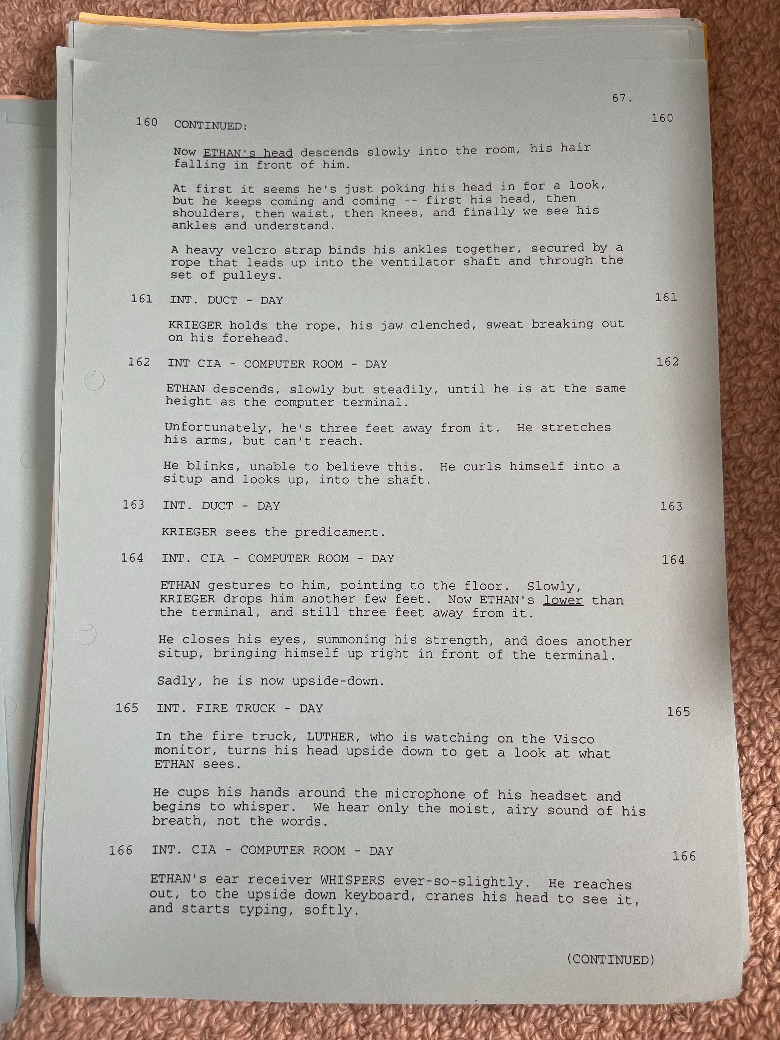

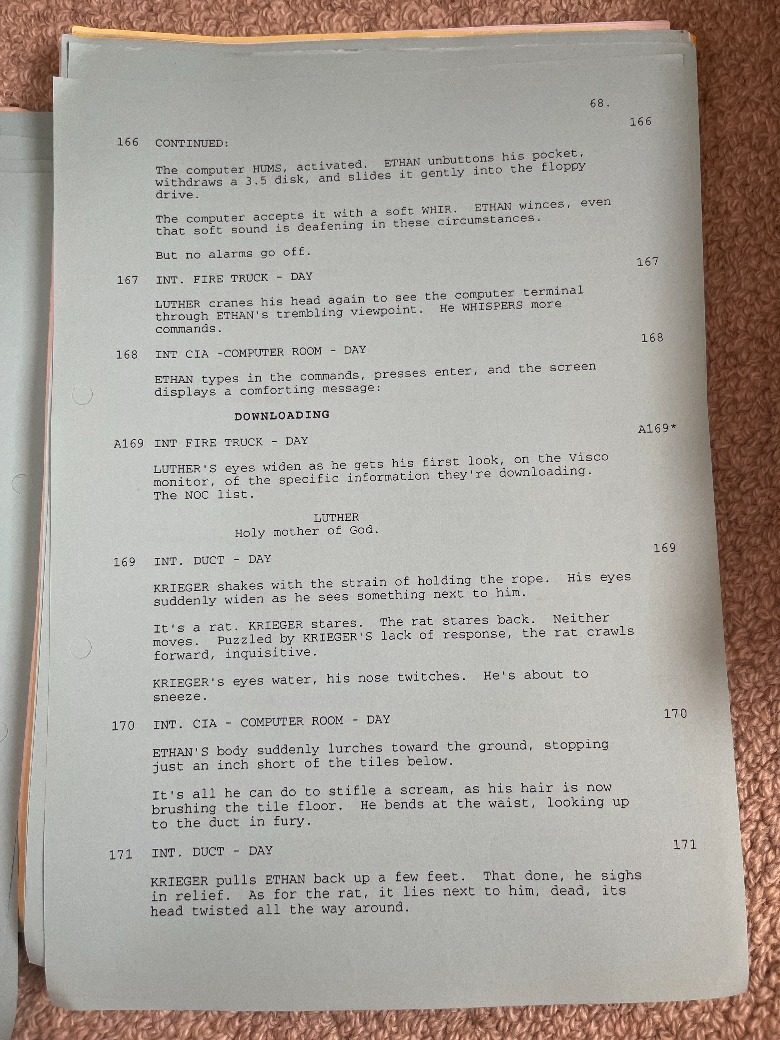

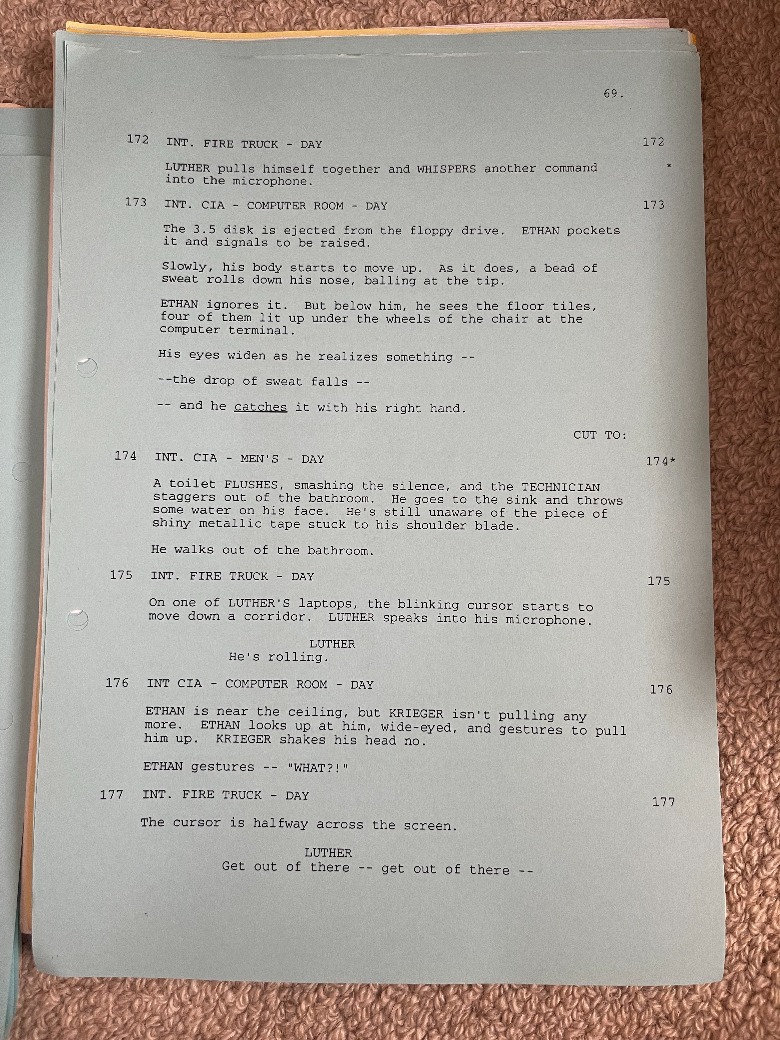

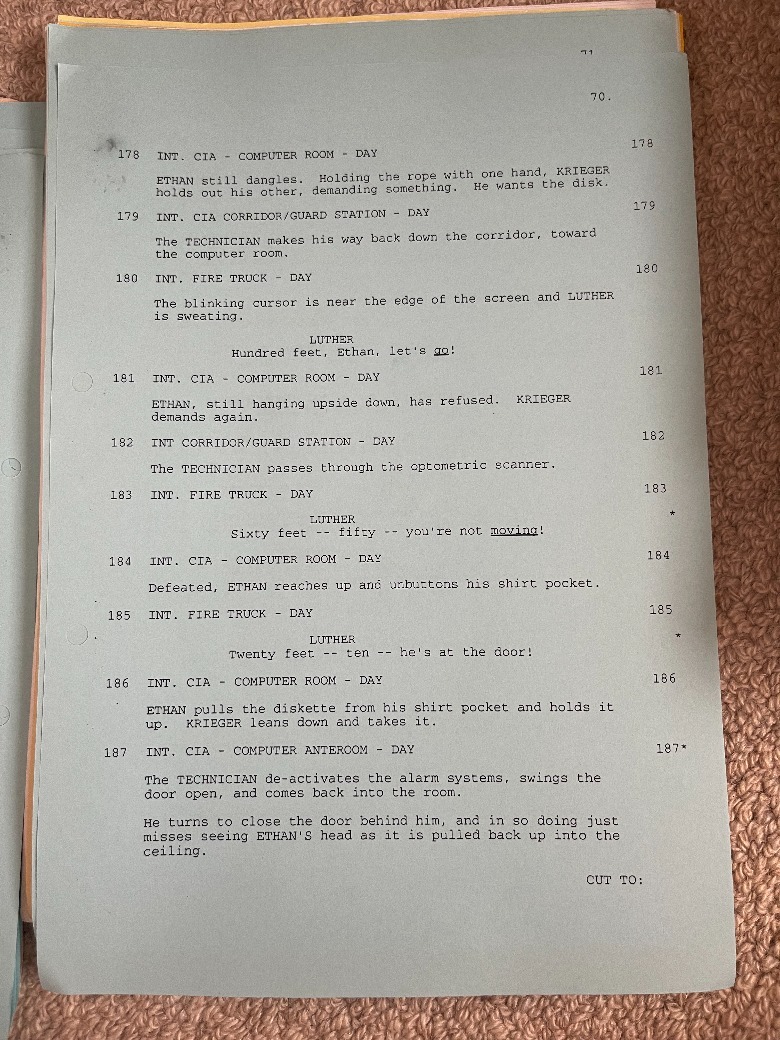

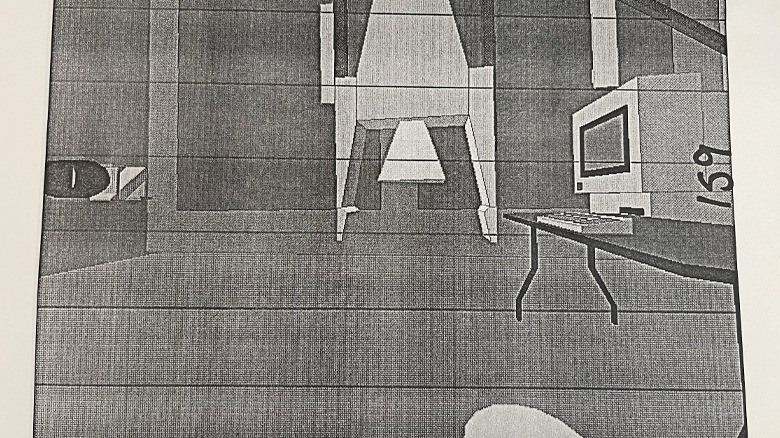

Before our interview, first assistant director Chris Soldo went into his personal archives and found a treasure trove of "Mission: Impossible" information, including the call sheets from every day of filming the Langley heist scene and the shooting script with the finalized draft of the screenplay describing the scene. It's fascinating to read the differences between what was written and what ended up in the final cut, and it provides a window into De Palma's willingness to try new things and let the best idea win. There are several noticeable differences here, but note that Krieger's sneeze in the vent isn't present in the script, and how, when Ethan is dropped, he was originally intended to be fully upside down with his hair "brushing the tile floor."

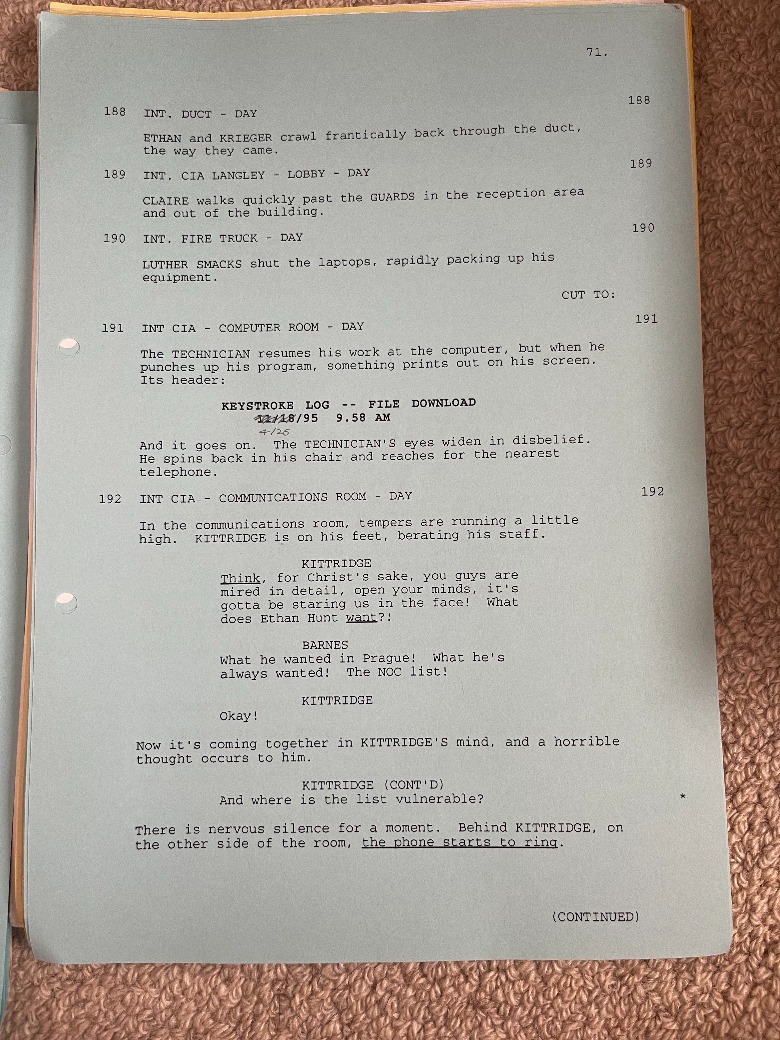

Here's the call sheet for the first day of filming the Langley scene:

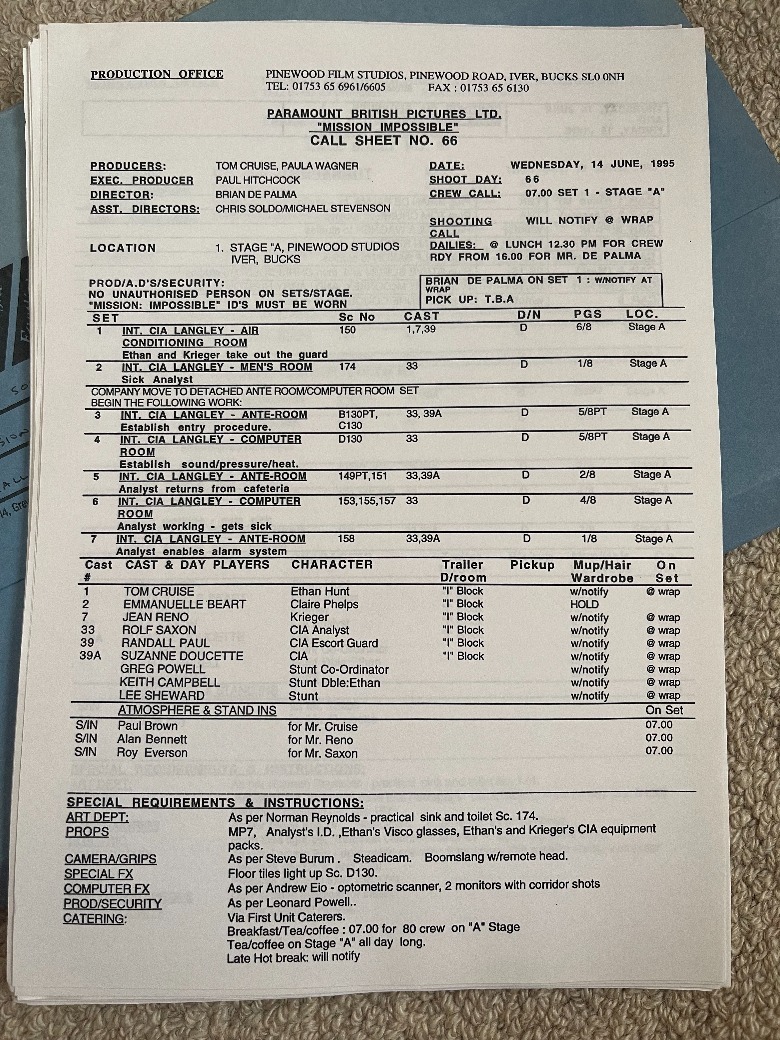

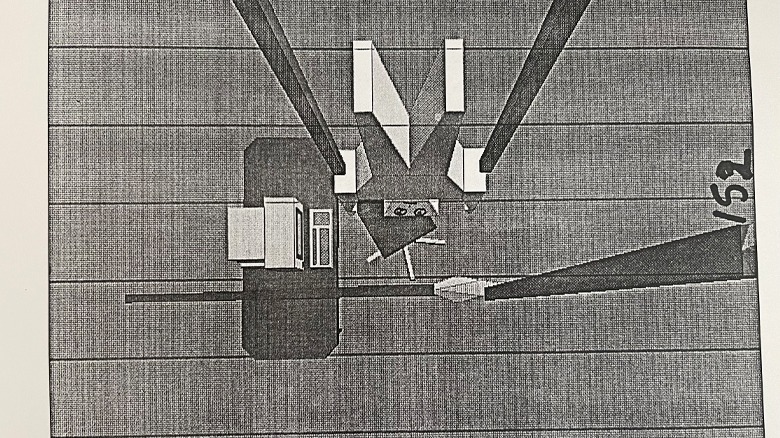

I was especially taken with the following images, which are storyboards made by Brian De Palma himself. Soldo told me the director was "fooling around with what was then a very new piece of software" which allowed him to make 3D models and place the camera in 3D space. "Brian would literally slave over these models for, God knows, days, wherever he was living and then make the decision to capture certain frames to put the storyboards together," Soldo said. "He was doing that all himself."

Feast your eyes on what can only be described as an extremely 1995 set of images, complete with De Palma's hand-written notations:

'None of us at the time knew we were making an iconic scene'

Paula Wagner: Making any and every movie has its own set of challenges. It is always pressured because as a producer, you are working with, and sometimes against, the clock, the weather, the budget, the location, schedules, timing. Making any movie is like a mission impossible. [laughs] So yes, this was a challenge, but it was a great challenge to be met and it took a lot of careful planning. And Tom, as producer and star, had incredible experience on set as an actor. And he completely understood the dynamics of movie making. I had been an actor myself years ago and been on sets, and spent much of my agent career on sets. It was a natural evolution to become a producer. And yes, every minute of filmmaking is a wonderful challenge to be undertaken. [Note: "Mission: Impossible" was the first project for Cruise/Wagner Productions, a production company run by Tom and Paula that produced films like "The Others," "Shattered Glass," and "Valkyrie" before shuttering in 2008.]

JC Calciano: When I look out of my house, the cable company that I use or whatever, there is a faux picture of somebody, like the Tom shot, on the side of the truck. I don't think it's Tom. It's just an advertisement. But I look at this truck, and I'm thinking, "None of us at the time knew we were making an iconic scene." We were just like, "Oh, this is the script, and hopefully it's part of the movie." You'd never at the time think, "This is going to be this iconic scene of a movie where people 30 years from now will duplicate, it'll be on the side of an ad of a truck" or anything else. It's just part of a bigger thing that we're all doing and part of something that we hope all of it's cool, and it all fits together.

Paula Wagner: You don't grasp the extent that something is a showstopping moment when you're right in the midst of making a showstopping moment. There is no time to be thinking, "This moment is going to change moviemaking." You just know that it's vitally important and must be executed properly.

JC Calciano: My husband designs museums, and one of the things he told me about Disneyland is that in Disneyland — this is maybe a little crude, but whatever — in Disneyland, they have a thing called "the big weenie." Always when you're walking through the park, there has to be a big thing that catches your eye, the big weenie. That's the Matterhorn, or it's Space Mountain. So there's a lot of stuff, but whenever you are in that space, there's a big weenie to draw your attention to.

I think that we were, at the time, making several big weenies in the movie. [The CIA heist] was one of them. Certainly at the time, the helicopter scene, the Chunnel scene, if you were sitting here and we were mapping out the movie, we would be like, "All right. Well, there's this, and then there's this. Then there's this, and then there's this," because we also blew up a car. I remember we were in Prague, and we had a barge coming down the lake, just creating fog. All that fog — you talk about old school. We wanted a foggy day, so we got a barge, and we just had tons of fog machines fogging up. It wasn't like we're fogging up a studio. We are fogging up a city. So we had a barge full of fog, making that entire city foggy on a night that's not foggy. Then we have a car that's not only going to blow up, but flip over and stuff.

So how could I sit there and go, "Well, all right. Lowering Tom in Langley is going to be iconic, but making a whole city foggy and blowing up a car, or racing a train through the Chunnel with Tom Cruise standing on top of it with 100 mile an hour wind, or Jon Voight dangling underneath a helicopter, or a helicopter going into the tunnel and exploding...?" Everything is just like, "Let's just keep going more and more and more." So it was all supposed to be special.

The Tom Cruise factor

JC Calciano: Princess Diana came to set one day. So that's how much [attention] we were getting, because Tom was there. It was a funny story that I get a phone call. Now, I'll tell the story. It doesn't put me in the best light, because I was a 30-year-old, 30, maybe, young guy, American, not really savvy to the royals or any of the English stuff. But I get a phone call that said, "Princess Diana would like to come to the set. Can she have a tour?" So I'm like, "It's your country. Sure. She wants to come." So she showed up, and she just rolled in. She didn't have anyone other than Harry and William with her. She just rolled in, and one of the production staff comes in into my office, ashen. They're like, "Princess Diana is in the production office, asking for you." Nobody knew, and I didn't think to tell them. So she came in, and I was like, "Oh, all right. I'll be right there."

Anyway, so then she came in, and she was lovely. I showed her around the whole location and stuff, and she's like, "Oh, can I meet Tom Cruise?" I was like, "Yeah, let me tell him you're here," which I hadn't even thought before, like, "Oh, let me prepare anyone for her." So she came, and then it's like, "Tom, could you see Princess Diana?" He's like, "Of course. Of course. Set it up. Set it up." I'm like, "No, no, no. She's right here." He goes, "She's here with you?" I was like, "Yeah, I'm showing her around." [He was] like, "No, no, God. Come in. Come in. Come in." It was just funny how casual it was.

Keith Campbell: Everybody says, "Hey, tell us the story about your career and stuff," and [this] is the best story of my entire career. Because I was in there rehearsing, hanging upside down, coming down from the ceiling, and the door of that set opens up and in walk Tom Cruise and Princess Diana and William and Harry. They came to visit the set and that's where I got to meet them. It was just unbelievable. I was hanging upside down and Tom introduced me to Princess Diana and the boys while I was hanging upside down and she reached up and shook my hand. It was so sweet.

Paul Hirsch: Brian has this rule: No actors in the editing room and no producers in the editing room. So before the picture started, I said, "Well, here you have Tom, who's the star and the producer. What are you going to do if he wants to come to the editing room?" He says, "I'm going to tell him no. He can see the picture as many times as he want in a screening room and give me all the notes he wants, but he's not coming to the cutting room." I thought to myself, "Well, we'll see how that works out." And it did. He never once came to the editing room. I mean, he might have come to say hi, but never sat down and worked in the editing room.

So I really had very little contact with him. And then when they were shooting the picture, Tom was on the set and I was in the cutting room. So I didn't really have that much contact with him during the shooting, either. So when I got to Prague on ["Mission: Impossible — Ghost Protocol"], he walks in, he gives me this big hello. I was surprised he even remembered me because we'd had such little contact on the first film. He said, "How have you been?" I said, "Well, I'm fine, but unlike you, I've changed in the last 15 years." He seemed to be exactly the same.

He's completely focused on work, the hardest working man, always positive. I'd see him and say, "How you doing, Tom?" He says, "Making a movie!" Like, "What else?" Like he's the happiest person on Earth, making a movie. What could be better than making movies?

Keith Campbell: Of all the "Missions," [the first one is] still my favorite.

Paula Wagner: I loved it. I loved the excitement. It was exhilarating. And working with Tom and a great team. I'm proud that "Mission 1" led the way for a phenomenal franchise that will probably go on and on and on. Possibly forever!